Britten was less in the Weekend than the annual title suggested, however significant and striking the works: a singular song cycle, an anguished early viola solo transcribed for cello and a minute-long final sketch. His influence was strong, it’s true, in unforgettable inspirations by Cheryl Frances-Hoad and Philip Moore. Their texts, by Ian McMillan and Dietrich Bonhoeffer, declared the real connection in two of the finest small-scale concerts I’ve heard this year: remembrance.

Because it was this, white-poppied as well as red, which threaded the deep thinking and feeling, and brought before our eyes and ears figures as diverse as Sophie Scholl, the 22-year-old who sacrificed her life in passionate, eloquent defence of her country’s true soul, and cellist Rafael Wallfisch, who – it may be obvious, but it kept striking me – wouldn’t be here at all if his mother Anita Lasker-Wallfisch (still I gather robust at 100) hadn’t survived the worst horrors.

Remember, exhorts one of the finely-worded pamphlets distributed by the White Rose movement of which Scholl remains the best-known figure, to a largely apathetic German population in 1943. Or rather, more fiercely, “to show your love for the coming generation… do not forget the petty villains of this regime, remember their names so that not a single one goes free" (and well we know to whom that applies in 2025). Could the choral works performed by Sansara under Tom Herring reflect some of the ferocity in the texts introduced by Dr Alexandra Lloyd of Oxford University’s White Rose project, translated by students and read by Tesni Kujore and James Meck – not just the brilliant blade of the pamphlets, but the poignant and disturbing letters of the imprisoned members trying to stay brave before their executions?

As it turned out, all the balances were exactly right (★★★★★). Many of the German pieces in the first half reflected Scholl’s frequent observation that “music softens the soul”, from Clara Schumann’s “Abendfeier in Venedig” to Mauersberger’s Psalm 39 setting, and back to Bach and Schutz. But the tougher way was seeded in Cecilia McDowall’s deliberately uneasy blend of words by Edith Cavell and Seán Street. And the grit in the oyster came between letters from prison – fathers to wives and the children in whose future they believed, the young White Rose folk with a more desperate, isolated yearning to stay strong – in the shape of Philip Moore’s Three Prayers of Dietrich Bonhoeffer. You could connect these to the world of War Requiem: the keening minor seconds of “Morning Prayers”, the tritones of “Prayers in Time of Distress”, the tortuous way to major triads – but they had very much an identity of their own.

The killer blow came with each strain of Ethel Smyth’s part-song on the chorale tune to “Komm, süsser Tod” as photographs of the White Rose participants appeared slowly, one by one, with dates to drive home how short were the lives of many of them. But what a legacy.

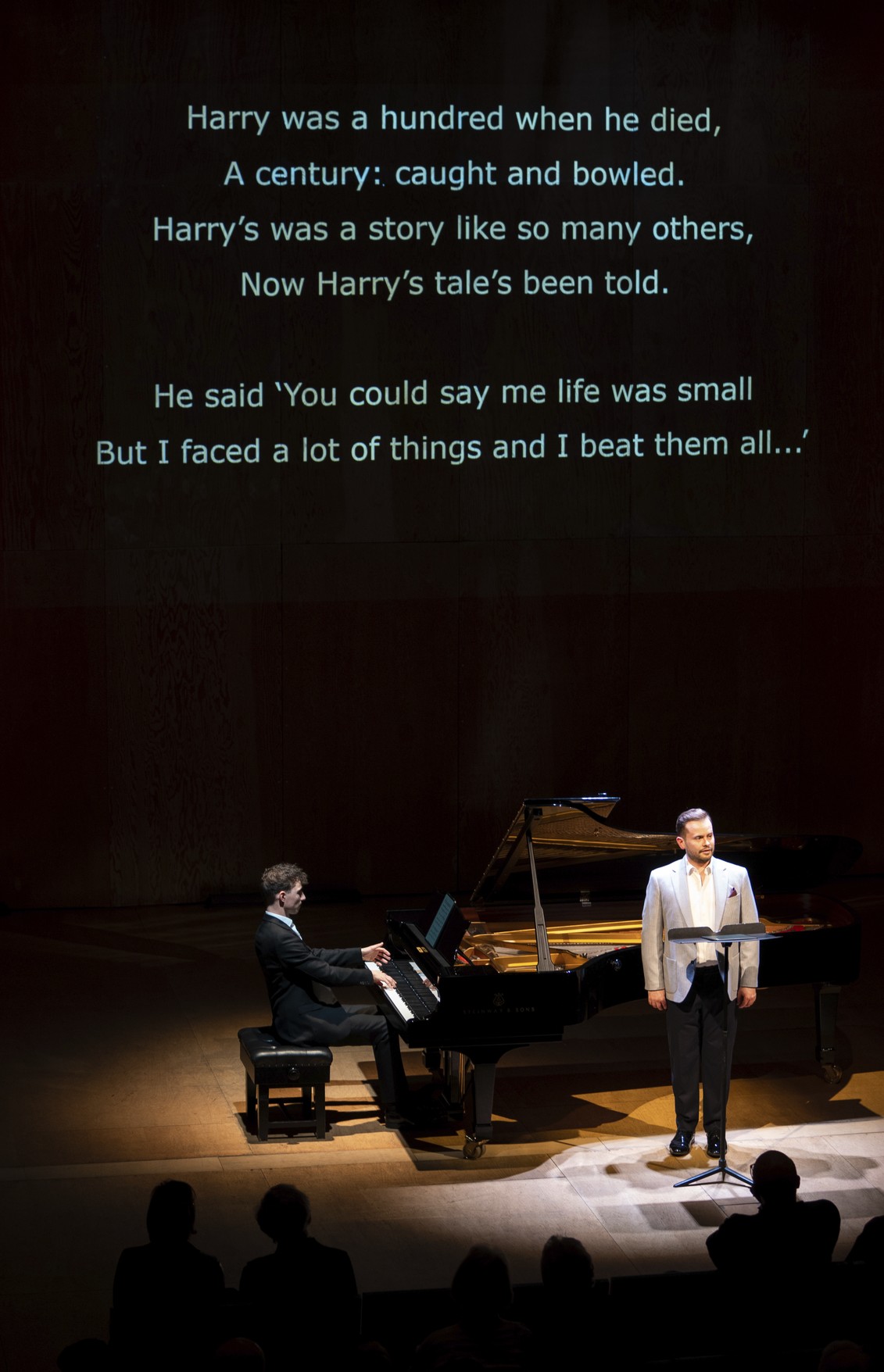

Counterpoint to Moore’s Bonhoeffer settings came the following afternoon in Cheryl Frances-Hoad’s vivid response, in Magic Lantern Tales, both to poems about First World War survivors, male and female, by Ian McMillan, and to the memory, sometimes oblique, of familiar songs. Which is why tenor Liam Bonthrone and Benjamin Mead, fine-tuned from the start (★★★★★), began with Butterworth’s “The lads in their hundreds”, echoed in “Marching through Time”. There was, surprisingly perhaps, a showstopper: “The Ballad of Harry Holmes”, a man content until his death at 100 through the vicissitudes of a life that shouldn’t have been interrupted by the horrors of war.

Bonthrone and Mead, a super-sensitive song partner to a brilliantly dramatic singer, made counterpoint of their own, breaking up Frances-Hoad’s settings with Britten’s Who Are These Children?, often aphoristic settings of pithy poems both in Scots dialect and not by Bonthrone’s compatriot William Soutar, from deadly serious (“The Old Aik”) to pithy-cheerful (“The Larky Lad”). A Britten scholar doubted the wisdom of not keeping them as a whole, but I respected the threading and, besides, many of us had been lucky to hear Nicky Spence and Malcolm Martineau reveal what a great cycle this is among the complete Britten songs performed here not so long ago, War ballads and laments by Debussy, Poulenc and Hugo Wolf rounded out the programme, though Novello’s “Keep the home fires burning” felt facile after what had gone before; better the encore, Haydn Wood's lovely “Roses of Picardy”.

These two programmes and their peerless execution were quite enough for a festival of remembrance. You had to take what you could from the rest. The Saturday evening concert (★★★) did at least give us a decent performance, especially good in biting anger, of Shostakovich’s Eighth String Quartet – both war and personal memorial – arranged by Rudolf Barshai as the Chamber Symphony. The official rest was not so good: an under-rehearsed shot at Beethoven’s Leonore No 1 Overture, sounding especially uninspired from the not very prepossessing English Chamber Orchestra (who knew they were still going?) conducted by Łukasz Borowicz and resurrection of a mostly justly neglected concerto, the nearly-80-year-old Arthur Bliss’s for cello, commissioned by Britten for Rostropovich to play at the 1970 Aldeburgh Festival.

Raphael Wallfisch gave it all serious and well-tempered consideration. But the opening actually promised worse than we got, sounding especially horrible in its angularity given some dodgy horn-tuning. The concerto gets better, the fray melting away across the course of the long first movement, and the Larghetto hinting at neo-classicism with its rather fine writing for two flutes. The finale is effective enough. But Wallfisch justified the whole evening with the encore – clearly no-one had told cross-looking leader Stephanie Gonley that there was going to be one, as she bumped into a returning cellist on her precipitate exit: his cello transcription of a sincerely anguished piece the 17-year-old Britten wrote days after leaving Gresham’s School.

We heard it again at very privileged close quarters in the library of the Red House the following lunchtime (if ever I coveted a room anywhere, it would be this one, now full of valuable pictures and an enviable collection of art books, inter alia). Wallfisch was here again, this time with pianist Simon Callaghan (★★★★). The knockout here was Bridge’s massive Cello Sonata of 1913-17, another commemorative gem. Callaghan managed the big-boned piano recital, no more, no less, but Wallfisch played his heart out. Commenting at the end, he said he felt the final major chord was as hard won as the one at the end of Britten’s Cello Symphony (if only that had been on the menu the previous evening).

We heard it again at very privileged close quarters in the library of the Red House the following lunchtime (if ever I coveted a room anywhere, it would be this one, now full of valuable pictures and an enviable collection of art books, inter alia). Wallfisch was here again, this time with pianist Simon Callaghan (★★★★). The knockout here was Bridge’s massive Cello Sonata of 1913-17, another commemorative gem. Callaghan managed the big-boned piano recital, no more, no less, but Wallfisch played his heart out. Commenting at the end, he said he felt the final major chord was as hard won as the one at the end of Britten’s Cello Symphony (if only that had been on the menu the previous evening).

The young Britten’s elegy was twinned with a last sketch from the last months of his life, the Tema “Sacher” requested by Rostropovich to mark the 70th birthday of the great patron. The rest was smaller beer: straightforward and slightly over-extended Impressions by the Dutch composer Henriëtte Bosmans, who had warmed to the young Britten, and Ireland’s slightly strained G minor Cello Sonata. I’ve been earwormed ever since this sunny Aldeburgh morning by the encore, a transcription of the great, simple Britten folk-song arrangement “O Waly, Waly”.

Add comment