'Everyone who played for him always gave their very best': remembering Bernard Haitink (1929-2021) | reviews, news & interviews

'Everyone who played for him always gave their very best': remembering Bernard Haitink (1929-2021)

'Everyone who played for him always gave their very best': remembering Bernard Haitink (1929-2021)

Singers, instrumentalists, conductors and a photographer pay loving homage

Few musicians get to stage-manage a dignified departure from the world.

We’re left with glowing memories of so much. One thinks immediately of his long-visioned interpretations of Brahms, Bruckner and Mahler symphonies; his first recordings of the Mahler symphonies, alongside Bernstein’s, did much to prompt the Mahler craze of the 1960s and 1970s. But though no pioneer in contemporary music, he did explore unexpected corners - at Glyndebourne, for instance, Britten’s Albert Herring and Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress at a time when it was by no means standard repertoire the world over (he also conducted Stravinsky ballets during his time at the Royal Opera House).  In addition to the last three concerts, personal highlights would be his Beethoven and Bruckner Sevenths with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra at the Barbican, the Beethoven Sixth at the Lucerne Festival, the transparency he brought to fairy-tale Siegfried in the Royal Opera Ring, the utter naturalness of his Meistersinger and Parsifal, the incredible detail of his Der Rosenkavalier and the dark focus on Verdi’s Don Carlos (one of two Verdi operas he favoured, as he told me in a fascinating interview in Verdi anniversary year). On CD – what a difficult choice – it would have to be his championship of Strauss’s Daphne with Lucia Popp. That special incandescence in the great final transformation scene makes it a desert island disc for me.

In addition to the last three concerts, personal highlights would be his Beethoven and Bruckner Sevenths with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra at the Barbican, the Beethoven Sixth at the Lucerne Festival, the transparency he brought to fairy-tale Siegfried in the Royal Opera Ring, the utter naturalness of his Meistersinger and Parsifal, the incredible detail of his Der Rosenkavalier and the dark focus on Verdi’s Don Carlos (one of two Verdi operas he favoured, as he told me in a fascinating interview in Verdi anniversary year). On CD – what a difficult choice – it would have to be his championship of Strauss’s Daphne with Lucia Popp. That special incandescence in the great final transformation scene makes it a desert island disc for me.

I’ll also never forget the simple wisdom of his Lucerne masterclasses with young conductors, the immediate difference to the orchestral sound when he took over to demonstrate. I got to speak to him for a happy and treasured ten minutes there. But the chapter and verse I’ll happily leave to one of his infinitely grateful acolytes, Mariano Chiacchiarini. Singers and orchestral musicians loved and respected Haitink’s firm leadership. In addition to Mariano, soprano Felicity Lott, bass John Tomlinson, Vienna Philharmonic Chairman and violinist Daniel Froschauer, and two other experienced musicians who have turned to conducting relatively recenty, Catherine Larsen-Maguire and Peter Manning, tell us why. It also seemed only right that Chris Christodoulou, master photographer whose images grace this tribute, should make his own tribute. David Nice

Mariano Chiacchiarini, conductor

"Let the music speak for itself".

I had the opportunity to meet Bernard Haitink for the first time in his 2011 masterclasses at the Lucerne Festival. And I had the pleasure to continue encountering him at the following festivals where I was no longer a young student but a guest conductor. From that first moment I was impressed. In a musical world where the market mostly imposes what the place of the artist should be, finally to be able to find someone whose aura was outside that business felt remarkable to me: it has always been the the aura of the music itself shining through him. His message was clear: music above all, only music matters.  It is difficult to describe the way in which Haitink achieved through his hands and the connection with his musicians the continuous flow of music, whether by Bruckner, Mahler or Beethoven, as if it were something absolutely natural and he, the conductor, only the composer’s intermediary. With him something as ephemeral as a piece of music could reconstruct itself every time in the most beautiful and genuinely way. From his lessons I remember his insistence to us young conductors to let the music speak for itself, to let it flow, without show or exaggeration, only love and respect for what we love the most and choose as the path for our lives: the music.

It is difficult to describe the way in which Haitink achieved through his hands and the connection with his musicians the continuous flow of music, whether by Bruckner, Mahler or Beethoven, as if it were something absolutely natural and he, the conductor, only the composer’s intermediary. With him something as ephemeral as a piece of music could reconstruct itself every time in the most beautiful and genuinely way. From his lessons I remember his insistence to us young conductors to let the music speak for itself, to let it flow, without show or exaggeration, only love and respect for what we love the most and choose as the path for our lives: the music.

Since the sad news of his departure, I can't stop thinking about his Mahler Four with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe two years ago. I am so profoundly thankful for having been able to visit those rehearsals and that unforgettable concert during my breaks with the Lucerne Festival Academy Orchestra. "There is just no music on earth that can compare to ours" says the text in the song finale. He brought us perhaps closest of all to this musc of the angels. Maestro Haitink, all the best for your journey, full of new incomparable heavenly melodies.

Chris Christodoulou, photographer

Over the past 40 years it has been my privilege to have photographed maestro Haitink on over 30 occasions.

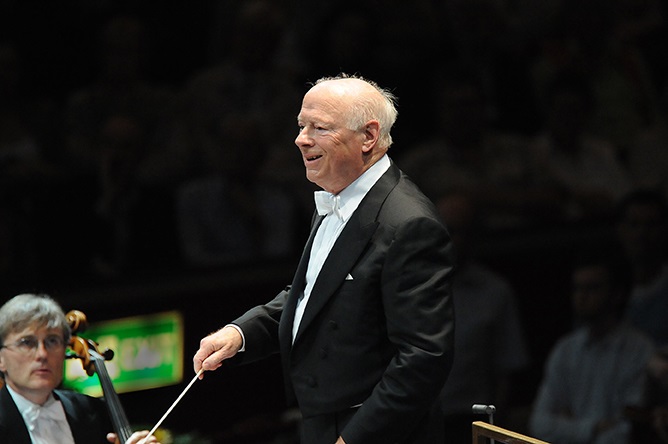

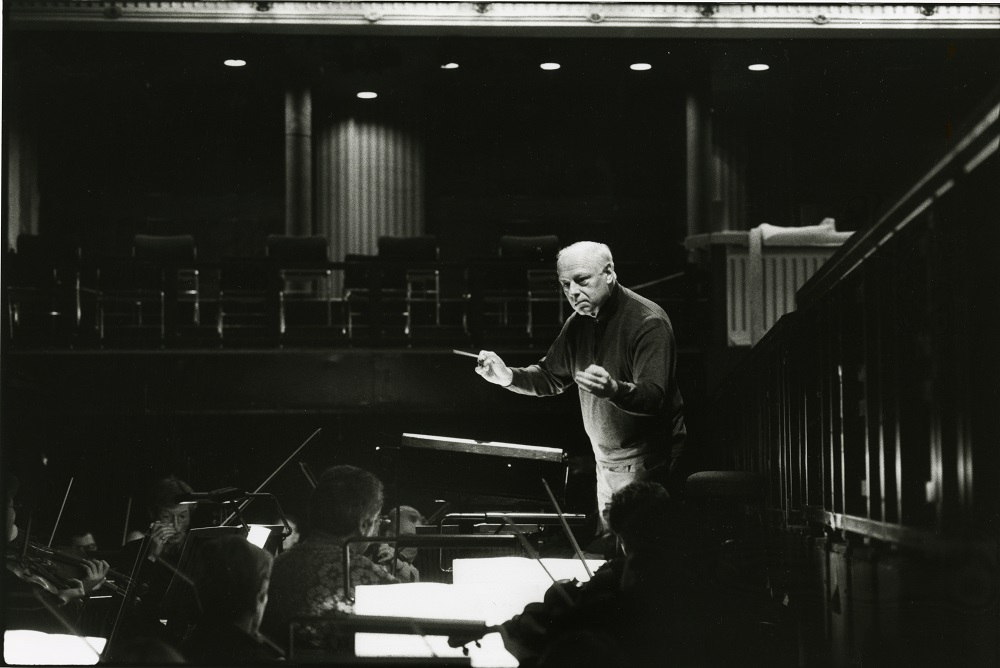

What was immediately apparent to me from even the early days was that it was about the music and not about him. Photographing rehearsals was so enlightening even for me as a non-musician; I could hear and understand just what he required, guiding orchestras in a confident and gentle way and drawing the very best from them [Haitink in one of Chris Christodoulou's photos from the Proms pictured below].  When you are the best at your profession you make things look easy and effortless. Haitink was just one of those legendary conductors. Could anyone who attended them forget his recent visits to the Royal College of Music to conduct the RCM Symphony Orchestra? His Mahler Second with them will live with me for ever.

When you are the best at your profession you make things look easy and effortless. Haitink was just one of those legendary conductors. Could anyone who attended them forget his recent visits to the Royal College of Music to conduct the RCM Symphony Orchestra? His Mahler Second with them will live with me for ever.

Thank you, maestro Haitink, for the joy and happiness you have brought to our hearts with your music over so many years.

Daniel Froschauer, Chairman and first violinist of the Vienna Philharmonic

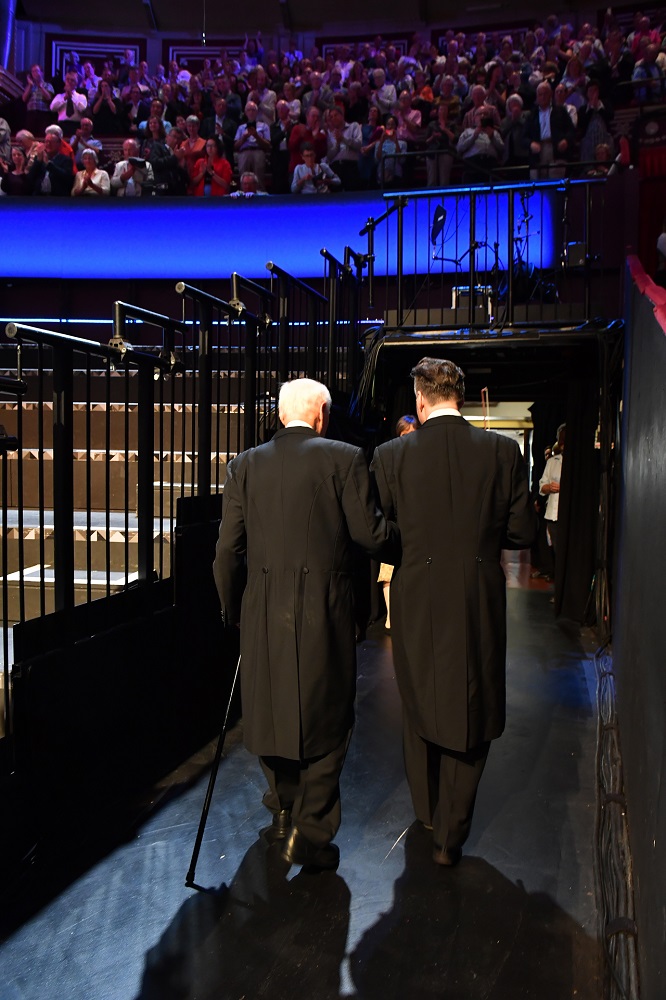

The last concert tour with Bernard Haitink in September 2019, which included appearances at the Salzburg Festival, the BBC London Proms [both images of Froschauer leading Haitink off the platform at the Royal Albert Hall by Chris Christodoulou] and the Lucerne Festival, will remain unforgettable. The concerts were characterized by an unusual intensity and depth, as one could feel that these were the great conductor's farewell from the concert stage. The last concert at the Salzburg Festival featured Anton Bruckner's Seventh Symphony, and I remember very clearly the first-movement transition to the E major coda in E Major, which Haitink conducted with such an inner intensity that it felt as if the Festspielhaus to open and heaven revealed. Yet this was not a loud farewell with pathos, but unpretentious and humble, which reflected the maestro's personality.

The last concert tour with Bernard Haitink in September 2019, which included appearances at the Salzburg Festival, the BBC London Proms [both images of Froschauer leading Haitink off the platform at the Royal Albert Hall by Chris Christodoulou] and the Lucerne Festival, will remain unforgettable. The concerts were characterized by an unusual intensity and depth, as one could feel that these were the great conductor's farewell from the concert stage. The last concert at the Salzburg Festival featured Anton Bruckner's Seventh Symphony, and I remember very clearly the first-movement transition to the E major coda in E Major, which Haitink conducted with such an inner intensity that it felt as if the Festspielhaus to open and heaven revealed. Yet this was not a loud farewell with pathos, but unpretentious and humble, which reflected the maestro's personality.

Bernard Haitink's conducting style was notable in that he knew exactly how to use his flawless stick technique to indicate exactly what he wanted and always maintain control over a performance. Every detail was meticulously conceived, and each finger conveyed its own expression, clearly indicating the musical idea he wished to communicate.

Haitink revelled in every detail of the sound. With his sovereign command and fluid movements, he was able to let go and allow the musical phrases to sing. He relaxed the pace and gave the music time; one never had the feeling that it was necessary to hurry. This produced an amazing sense of peace that intensified the expression, particularly evident in the slow movement of Bruckner's Seventh. The slower tempo lent the Scherzo more weight and revealed the extraordinary depth of the music. Yet there was nothing artificial about the deceleration of the tempi. Haitink's interpretations always possessed a dynamic authenticity that reflected his personality and enabled him to constantly maintain musical tension and vitality. His Bruckner interpretations were characterized by charm, decency, and grace, rather than the powerful gesture - the musical legacy of one of the finest conductors.

Haitink revelled in every detail of the sound. With his sovereign command and fluid movements, he was able to let go and allow the musical phrases to sing. He relaxed the pace and gave the music time; one never had the feeling that it was necessary to hurry. This produced an amazing sense of peace that intensified the expression, particularly evident in the slow movement of Bruckner's Seventh. The slower tempo lent the Scherzo more weight and revealed the extraordinary depth of the music. Yet there was nothing artificial about the deceleration of the tempi. Haitink's interpretations always possessed a dynamic authenticity that reflected his personality and enabled him to constantly maintain musical tension and vitality. His Bruckner interpretations were characterized by charm, decency, and grace, rather than the powerful gesture - the musical legacy of one of the finest conductors.

While in Salzburg, we presented Bernard Haitink with Honorary Membership of the Vienna Philharmonic, in recognition of our long-term artistic partnership that began in 1972. Those who experienced his conducting, whether on stage or in the audience, will never forget the depth and intensity of this final tour.

Catherine Larsen-Maguire, conductor and former bassoonist

Thinking about Bernard Haitink over the past couple of days, I’ve come to the conclusion that he was the conductor that has influenced me the most - as a bassoonist, a conductor, a musician and a person (in ascending order of importance). I first met Haitink in 1993, as the insignificant third bassoonist in the European Community (as it was then) Youth Orchestra, playing Mahler Nine on a European tour. Needless to say, the rehearsals were a revelation, and the concerts were some of the best I have ever been involved in.

Before the tour started, we had the usual chamber music evening, which included serious and less-serious items; I was playing in a slightly humorous bassoon trio (is there any other kind?) and Haitink was in the audience. After the concert he was chatting to the musicians, and turned to me: “What’s your name?...Ah, Catherine…do you know, you were born to play the bassoon?” I think that was a compliment - it was certainly meant as one! - and I have treasured his words ever since, even though I already wanted to conduct at that stage, and wasn’t sure whether being born to play the bassoon was necessarily a good thing.

Before the tour started, we had the usual chamber music evening, which included serious and less-serious items; I was playing in a slightly humorous bassoon trio (is there any other kind?) and Haitink was in the audience. After the concert he was chatting to the musicians, and turned to me: “What’s your name?...Ah, Catherine…do you know, you were born to play the bassoon?” I think that was a compliment - it was certainly meant as one! - and I have treasured his words ever since, even though I already wanted to conduct at that stage, and wasn’t sure whether being born to play the bassoon was necessarily a good thing.

Several years later I was playing as a guest in the BBC Symphony Orchestra, in a performance of Beethoven Nine in the Proms. Again, the rehearsals were a lesson in how to work selflessly and efficiently with an orchestra; the beat was always crystal clear, there was never any show or extraneous gesture, no grunting or groaning or dramatic flicking back of hair, and the result was of course magnificent. By this time I had graduated to playing first bassoon, and so I dared to approach Haitink in the break to ask a question about a point of articulation. He looked at me for a long moment and said “Is it...Catherine? The one who was born to play the bassoon?” I was so completely overwhelmed that I could hardly stammer out my question, and I returned to my seat with tears in my eyes. By this time I was doing a lot of conducting myself, and I resolved at that moment that his was the example that I would always try and follow.

This anecdote is not meant to be about me; I’m sure many orchestral players have similar stories. I wanted to share it because it shows so perfectly what kind of a musician and person Haitink was. For him, the orchestra wasn’t just a sea of faces (or even worse, a giant piano), but a collection of individuals who were musicians in their own right. Perhaps this is one of the reasons that he was universally loved and admired; it is certainly the reason why everyone who played under his baton always gave their very best, and why the orchestras that he conducted had such a special sound and a unique musicality.

This anecdote is not meant to be about me; I’m sure many orchestral players have similar stories. I wanted to share it because it shows so perfectly what kind of a musician and person Haitink was. For him, the orchestra wasn’t just a sea of faces (or even worse, a giant piano), but a collection of individuals who were musicians in their own right. Perhaps this is one of the reasons that he was universally loved and admired; it is certainly the reason why everyone who played under his baton always gave their very best, and why the orchestras that he conducted had such a special sound and a unique musicality.

Just a couple of years ago, after having seen and heard Haitink many times in Berlin, and after having long left the bassoon behind me [Larsen-Maguire conducting pictured above by David Beecroft], I flew to Amsterdam to listen to his very last rehearsal with the Concertgebouw Orchestra; coincidentally, it was Mahler Nine. Friends in the orchestra had ensured that I would be allowed to go into the hall to listen, but just a couple of minutes before the rehearsal began, it was announced that the rehearsal would be completely closed. I was extremely disappointed at first, but as I sat on the stairs backstage listening to the rehearsal, my only feeling was one of overwhelming gratitude.

The fact that we all remember him with such fondness, respect and admiration means that he will surely never be gone.

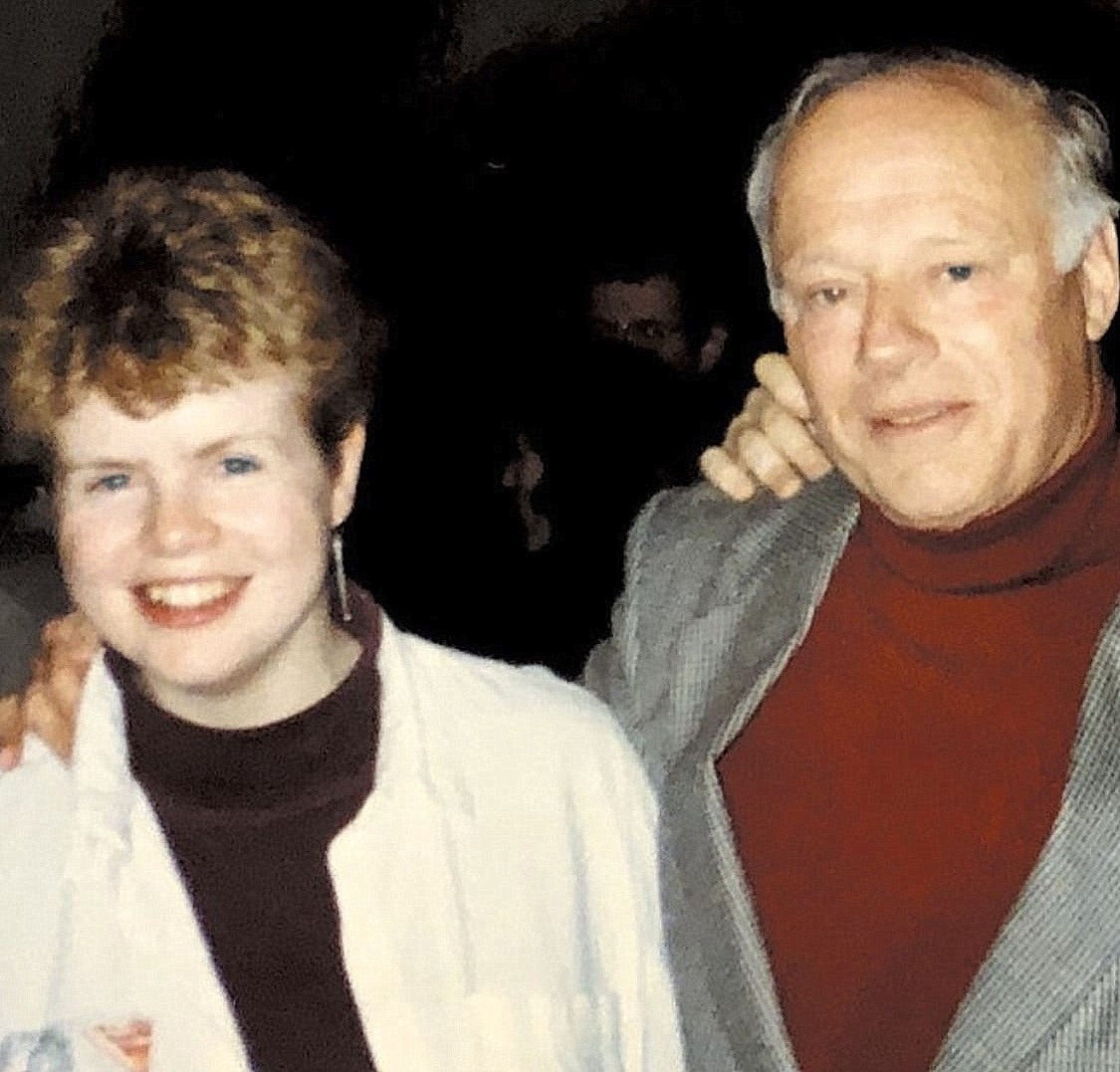

Felicity Lott, soprano  I’m eternally grateful to Bernard for so many opera performances and concerts. I suppose I had one foot through the Glyndebourne door with the rôle of the Countess in Strauss's Capriccio on the 1976 tour [Felicity Lott pictured above singing the final scene with Haitink and the London Philharmonic Orchestra at the 1992 Glyndebourne gala before the closure of the old house], but from 1977 onwards my summers were spent singing glorious music in that perfect Festival setting. It became almost the usual thing to see Bernard across the orchestra in rehearsals and performances, so I’m not sure that I realised what a great man he was.

I’m eternally grateful to Bernard for so many opera performances and concerts. I suppose I had one foot through the Glyndebourne door with the rôle of the Countess in Strauss's Capriccio on the 1976 tour [Felicity Lott pictured above singing the final scene with Haitink and the London Philharmonic Orchestra at the 1992 Glyndebourne gala before the closure of the old house], but from 1977 onwards my summers were spent singing glorious music in that perfect Festival setting. It became almost the usual thing to see Bernard across the orchestra in rehearsals and performances, so I’m not sure that I realised what a great man he was.

He also became a dear friend, and latterly we spent many happy evenings with him and his wife Patricia, where I could look at him across a dining table instead! Seeing and hearing him direct the vast symphonies of Mahler and Bruckner with such sure control of the architecture of these works, no histrionics, just letting the music speak, was awe-inspiring. It was an enormous privilege to know him and to work with him.

Peter Manning, conductor and former violinist

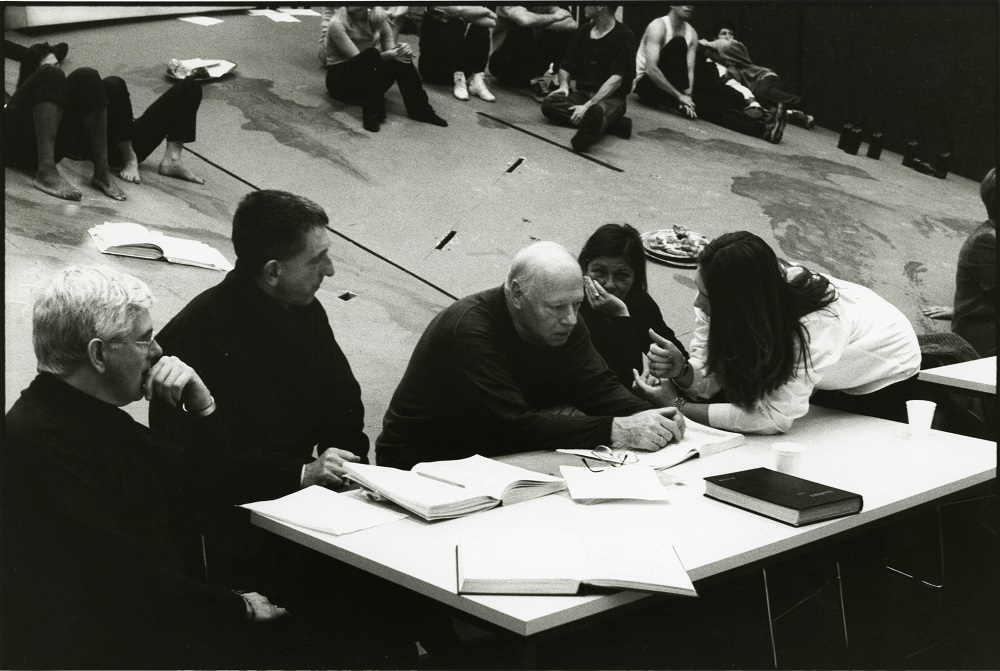

To a young musician at the beginning of a career the thought of working with a “musical touchstone” became possible when I returned from my studies in the USA and then happily began trialling for the position of leader of the London Philharmonic Orchestra, which at that time was under the general leadership of Sir Georg Solti. [Pictured below by Rob Moore: Haitink rehearsing the Royal Opera Orchestra in Verdi's Falstaff, 1999]  Bernard’s choice of programming and the creation of the settings both musical and at a human level for the possibility of great performances was made evident in the broadest possible musical worlds which he created and enabled particularly through French, German, Austrian and English repertoire. Every successive meeting and performance with him (aka the Bernard factor), the music rehearsals and his gentle guiding and purposefully shaped performances revealed layer after layer of deep musical communication from the composer’s score both for the orchestra, the soloists and the public. This I had only really heard in my favourite performances, predominantly on recordings. as I was growing up. To have been next to him, seeing him working on this shaping, was an immense and rare privilege.

Bernard’s choice of programming and the creation of the settings both musical and at a human level for the possibility of great performances was made evident in the broadest possible musical worlds which he created and enabled particularly through French, German, Austrian and English repertoire. Every successive meeting and performance with him (aka the Bernard factor), the music rehearsals and his gentle guiding and purposefully shaped performances revealed layer after layer of deep musical communication from the composer’s score both for the orchestra, the soloists and the public. This I had only really heard in my favourite performances, predominantly on recordings. as I was growing up. To have been next to him, seeing him working on this shaping, was an immense and rare privilege.

I hadn’t up to that point in the early 1980s met with anyone who so fully shared the personal intentions of the composer and working on my first opera with him, Mozart’s Die Entführung aus dem Serail, at Glyndebourne in an intimate rehearsal space was a truly magical and unforgettable process.

His clarity of intent spread across the orchestra in a way that few conductors can achieve, and I soon realised that his ideas of musical flow in his conducting and the obvious care for his musicians was really the reason that allowed for the continuing artistic and human growth of really great orchestras. [Pictured below by Rob Moore: Haitink in a rehearsal of Falstaff, 1999. His right-hand man at the Royal Opera David Syrus, also a fine conductor, is second from left]. Whether in Debussy, Ravel, Beethoven, Brahms, Mozart, Mahler, Sibelius, Elgar, Janáček, Verdi - the list goes on and on - all his appearances had this sense of living performance and all the freshness that goes with that.

Whether in Debussy, Ravel, Beethoven, Brahms, Mozart, Mahler, Sibelius, Elgar, Janáček, Verdi - the list goes on and on - all his appearances had this sense of living performance and all the freshness that goes with that.

The players adored playing for him as he allowed them to engage fully in a way that they could give of their best both technically and musically, in order to create the most wonderful ensemble performance possible. He guided us gently and clearly set a fine and generally agreed musical structure to allow for the most positive work.

That was I believe central to his work The outcomes were rarely other than special and artistically uplifting.

In my time as concertmaster of the Royal Opera House with him there were so many truly wonderful ppera performances. Janáček and Mozart especially flourished under his flexible and musical authority. Yet if there is one operatic interpretation that defines so much of this work it would for me be his last Covent Garden performance of Wagner’s Parsifal. Right from the first unison phrase of the Prelude to the glow of the closing moments, his pacing and musical narrative created musical transcendence – something that only Bernard could achieve.

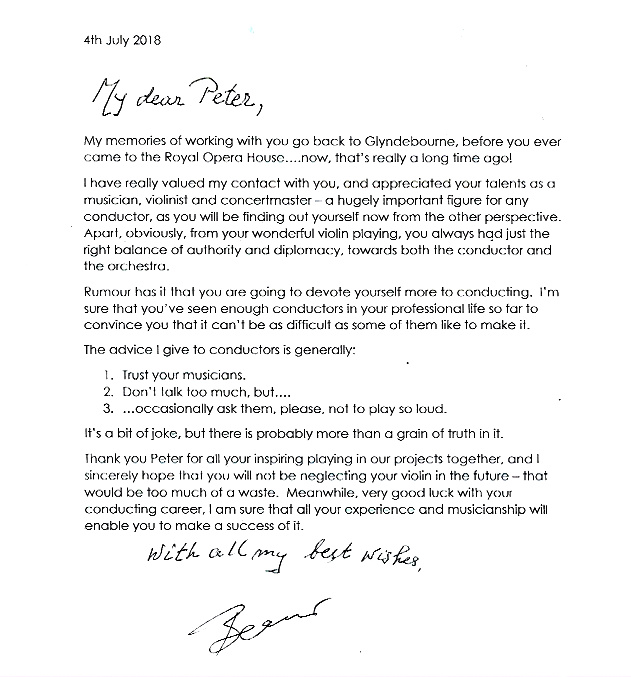

Below: a letter from Bernard Haitink to Peter Manning, 2018

John Tomlinson, bass

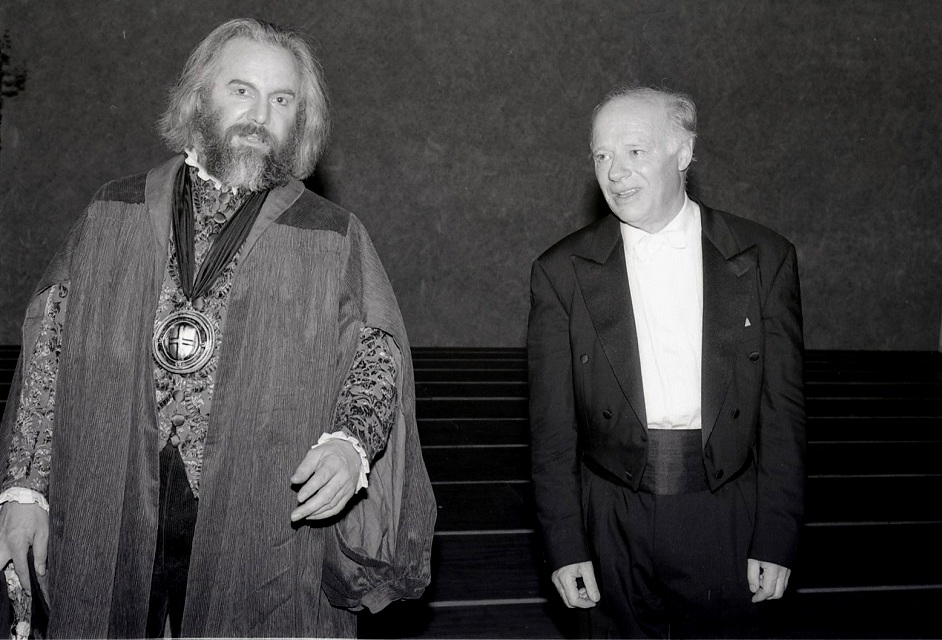

It doesn’t seem so long since I was writing an enthusiastic tribute to Bernard Haitink on the occasion of his 85th birthday. At that time, one had the feeling that this great conductor would go on forever, that he would always be there. The news of his death was a sad day for all of us music lovers, because from now on, Bernard will no longer be with us. He has been such an integral part of our musical lives, world wide, but particularly in Britain, that it’s hard to register the fact that he has departed. [Pictured below by Donald Southern: John Tomlinson and Bernard Haitink after a performance of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg at the Royal Opera in 1993] Off the podium, Bernard was a pensive, philosophical, self-effacing man; as a conductor in performance he was alert, perceptive, intense; but whether in or out of the spotlight, he was never showy or superficial; rather, he had a quiet authority, an easy sense of humour, an inner strength, and a telling, demanding look in the eye. That piercing glance I remember well throughout the many hours of operatic performance I was fortunate enough to share with him. Across the footlights one felt a companionship with him, a common joy to be partaking in the evolving story being played and sung by the whole company. And he made that story so vital and wonderful (in the real sense) to each one of us in that company.

Off the podium, Bernard was a pensive, philosophical, self-effacing man; as a conductor in performance he was alert, perceptive, intense; but whether in or out of the spotlight, he was never showy or superficial; rather, he had a quiet authority, an easy sense of humour, an inner strength, and a telling, demanding look in the eye. That piercing glance I remember well throughout the many hours of operatic performance I was fortunate enough to share with him. Across the footlights one felt a companionship with him, a common joy to be partaking in the evolving story being played and sung by the whole company. And he made that story so vital and wonderful (in the real sense) to each one of us in that company.

He leaves us all with deep, golorious memories, and a profound sense of gratitude, and of loss.

Thank you for everything, Bernard.

John Tomlinson’s tribute to Haitink on his 85th birthday

I was honoured to be asked to write about Bernard on a previous occasion, also for a Covent Garden Programme: it was in 2002 for his farewell performance as Music Director of the Royal Opera House after over 20 years in charge. I thanked him then, on behalf of us all, for his wonderful leadership and music making over those years, and I tried to put into words the qualities of a great performance under his direction. It’s impossible to explain great conducting, but I made a brave attempt; one recognises the phenomenon, but to explain how it’s achieved is beyond words or analysis. Almost twelve years have passed since that farewell performance. Twelve years of great success and stability for Covent Garden, and twelve years of further blossoming of Bernard’s conducting career during which he has worked as intensively as ever and with even greater acclaim from an ever more grateful public. [Pictured below by Donald Southern; curtain call after a performance of Die Meistersinger, 1993] Bernard’s achievements at Covent Garden, and the deep gratitude felt towards him, can only be understood by delving into the past and reminding ourselves of the pain suffered by the House during the years leading up to and during the closure of the theatre between the years 1998 and 2000. The closure was necessary and inevitable and the renovation and development of the site eventually hugely successful, but the process, at the time, was extremely traumatic for all involved. Those of us who worked through it will always be thankful to those, Bernard foremost among them, who kept the flag flying throughout. In recent months there has been a memorable Ring cycle at the Royal Albert Hall, and I am reminded of Bernard’s Ring in that same Hall back in 1998 which will be just as fondly remembered. It took place at a critical, dangerous time for the Company, with its House closed, and its very survival in jeopardy. The performances had a particular electricity and urgency. Bernard spoke directly to the audience, I remember, appealing for understanding and support from the public. They were “dark days”, as he himself described them later; it’s salutary to remind ourselves occasionally of the darker times, and the debts we owe to those who steered us through them.

Bernard’s achievements at Covent Garden, and the deep gratitude felt towards him, can only be understood by delving into the past and reminding ourselves of the pain suffered by the House during the years leading up to and during the closure of the theatre between the years 1998 and 2000. The closure was necessary and inevitable and the renovation and development of the site eventually hugely successful, but the process, at the time, was extremely traumatic for all involved. Those of us who worked through it will always be thankful to those, Bernard foremost among them, who kept the flag flying throughout. In recent months there has been a memorable Ring cycle at the Royal Albert Hall, and I am reminded of Bernard’s Ring in that same Hall back in 1998 which will be just as fondly remembered. It took place at a critical, dangerous time for the Company, with its House closed, and its very survival in jeopardy. The performances had a particular electricity and urgency. Bernard spoke directly to the audience, I remember, appealing for understanding and support from the public. They were “dark days”, as he himself described them later; it’s salutary to remind ourselves occasionally of the darker times, and the debts we owe to those who steered us through them.

Still recalling the past, but on a lighter note, I remember well my first performances with Bernard, way back in 1973 at Glyndebourne in Die Zauberflöte, when he would always gently chuckle for some reason unknown to me, at my (over-portentous?) delivery of the word “Wohltätig” in the German dialogue. I remember too my most recent performance with him in 2008 at the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam: Die Walküre Act 1, to great acclaim from his home audience. In between, I have had the pleasure of being on stage for a few hundred hours under his watchful eye, mainly of course, here at Covent Garden. I say “watchful eye” and mean it literally; it’s not only ever watchful, but incisive, questioning, demanding. At the same time there’s a sense of complete security and inner joy, a sense of unity in a common cause, a love of virtue, of noble aspiration in the music, of generosity, warmth, humanity. [A birthday greeting follows]

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

I'll never forget his