Alcina, Royal Opera review - sharp stage magic, mist over the pit | reviews, news & interviews

Alcina, Royal Opera review - sharp stage magic, mist over the pit

Alcina, Royal Opera review - sharp stage magic, mist over the pit

Soprano Lisette Oropesa and director Richard Jones hold Handel’s sensuous torch aloft

Handel’s audiences must have taken a very long time to settle – at least an act, to judge from the mostly inconsequential music of Alcina’s first hour. Lovely: we’re on an enchanted isle where puritanical people have been transformed into animal-headed courtiers, and a love-imbroglio merits only a “so what?” Richard Jones and his singers keep it lively and focused, but the bounce needed from Christian Curnyn and the Royal Opera House Orchestra doesn’t come.

Eventually the charm of the personalities and the consistency of the staging win over, but it does show how much a conductor’s pacing matters (and probably how the bite of authentic instruments helps Handel, though Mackerras used to simulate it well enough. Possibly, too, a seat in the Royal Opera's stalls circle beneath the overhang dulls the sound). Despite the succession of solo arias, many feeling too long with their middle sections and da capo repeats with ornamentations, this is an ensemble production, with the team of birds and beasts very often calling the tune, and unofficial ballet routines, in the brilliant Sarah Fahie’s quirky choreography, and Jones using Antony McDonald’s gorgeously malleable designs to keep the action flowing throughout the set pieces. Oh, those animal heads! Personal favourites? The mandrill and the King Charles spaniel.  Against all odds, sorcerer Alcina and her “love, love, nothing but love” motto form the dramatic and sympathetic focus through an astonishingly varied backbone of five arias: no staging can succeed without a consummate artist in the title role. Lisette Oropesa voice has that infallible ping and reach from the start, as she wields her brand perfume (pictured above, with Mary Bevan's Morgana left and Rupert Charlesworth's Oronte second from right) – Jones’s clever representation of the “magic urn” which must eventually be broken if her power is to end. The director’s demands for dramatic intensity are all met, from slinky prankster to near-demented love-reject. The emotional highlights – “Ah! mio cor” and “Ombre pallide” in Act Two – hit surprisingly hard. There’s trademark Jones unease as the puritanical cult from which lover Ruggiero comes threatens to gain the upper hand, and it looks as if we’re in for a dour curtain with the magic-wielders nowhere in sight; but then there’s an outrageously funny final gag (no spoiler) which shows the director at his most playful.

Against all odds, sorcerer Alcina and her “love, love, nothing but love” motto form the dramatic and sympathetic focus through an astonishingly varied backbone of five arias: no staging can succeed without a consummate artist in the title role. Lisette Oropesa voice has that infallible ping and reach from the start, as she wields her brand perfume (pictured above, with Mary Bevan's Morgana left and Rupert Charlesworth's Oronte second from right) – Jones’s clever representation of the “magic urn” which must eventually be broken if her power is to end. The director’s demands for dramatic intensity are all met, from slinky prankster to near-demented love-reject. The emotional highlights – “Ah! mio cor” and “Ombre pallide” in Act Two – hit surprisingly hard. There’s trademark Jones unease as the puritanical cult from which lover Ruggiero comes threatens to gain the upper hand, and it looks as if we’re in for a dour curtain with the magic-wielders nowhere in sight; but then there’s an outrageously funny final gag (no spoiler) which shows the director at his most playful.

Lustrous mezzo Emily d’Angelo doesn’t quite rise to the unique impressions she made as Mozart’s Sesto and Handel’s Serse – a few pitch problems might be related to the uncertain support from the pit – but the sublime farewell to "green meadows, pleasant woods" is certainly affecting, backed up by the retreat of the onstage greenery. And there’s no better example of how dance, drama and vocal pyrotechnics work hand in glove in this production than Ruggiero’s big showpiece, “Sta nell’ircana” (pictured below).  Its witty but slightly threatening ballet balances the disciplined high jinks around Morgana’s “Tornami a vagheggiar” at the end of Act One. There’s a curious gauziness about Mary Bevan’s upper register which momentarily distracts from the colour-artistry of her singing – tough to be second soprano when Oropesa rules the roost – but she’s such a meaningful performer, and “Credete all mio’dolore”, her suddenly serious-sensuous number with wonderful cello obbligato at the beginning of Act 3, is a real highlight, seduction balanced by the post-coital bliss of Oronte’s next number. His three arias make demands beyond the Handelian norm for tenor, and Rupert Charlesworth energises them all.

Its witty but slightly threatening ballet balances the disciplined high jinks around Morgana’s “Tornami a vagheggiar” at the end of Act One. There’s a curious gauziness about Mary Bevan’s upper register which momentarily distracts from the colour-artistry of her singing – tough to be second soprano when Oropesa rules the roost – but she’s such a meaningful performer, and “Credete all mio’dolore”, her suddenly serious-sensuous number with wonderful cello obbligato at the beginning of Act 3, is a real highlight, seduction balanced by the post-coital bliss of Oronte’s next number. His three arias make demands beyond the Handelian norm for tenor, and Rupert Charlesworth energises them all.

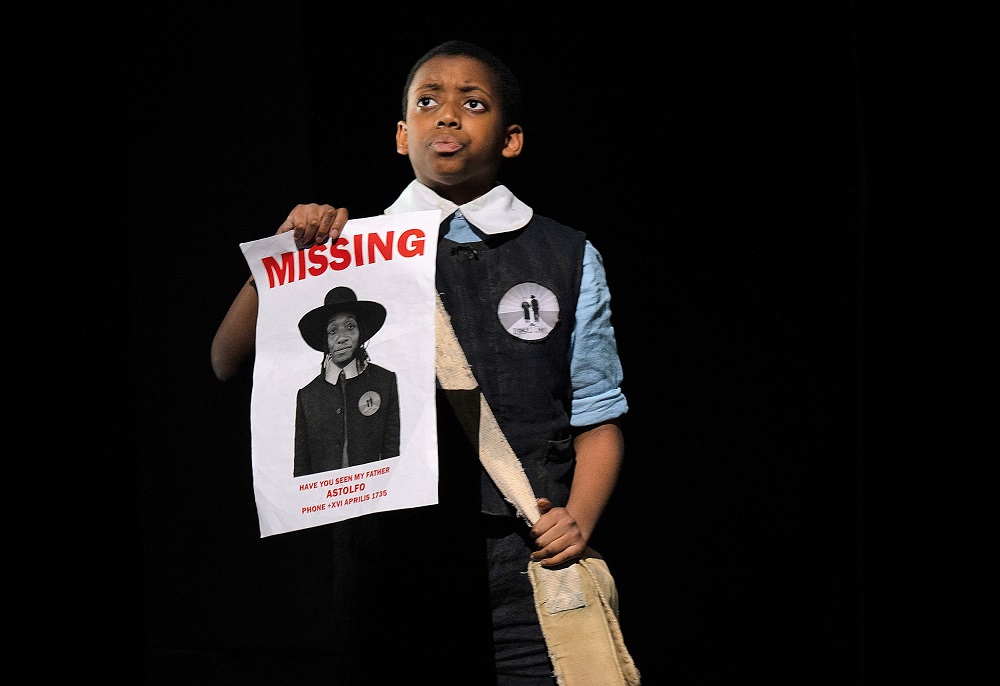

The Puritans inevitably sound dour by comparison, but Varduhi Abrahamyan as Bradamante and Jose Coca Loza as bass power-wielder Atlante fulfil the demands in style. The real scene-stealer is young Malaki M Bayoh (pictured below); Handel keeps plaintive Oberto’s arias short as the boy looks for his lost dad – the composer had a treble he wanted to showcase, though not overmuch – but the third especially makes some demands. I was not interested in whatever kerfuffle was going on with a clearly mentally unwell member of the audience during the second aria, too much highlighted on social media; the lad’s a star, and deserves every plaudit (the role will be taken in three of the performances by Rafael Flutter)..  I’ll not hide the fact that by personal disposition I’d rather have been at another first night, Irish National Opera’s for Rossini’s Guillaume Tell in Dublin – a triumph, I’m told – but by the end of another long evening, Handelians and others must have felt as well fed by this culinary opera as Ruggiero is, in the production, by Alcina’s strawberries. It just needs a kick in the pit.

I’ll not hide the fact that by personal disposition I’d rather have been at another first night, Irish National Opera’s for Rossini’s Guillaume Tell in Dublin – a triumph, I’m told – but by the end of another long evening, Handelians and others must have felt as well fed by this culinary opera as Ruggiero is, in the production, by Alcina’s strawberries. It just needs a kick in the pit.

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

Comments

Can you tell me what basis

No one would do that, out of

No one would do that, out of nastiness or racism (same thing), without being unbalanced. If I insult anyone, I insult myself, having experienced serious depression in the past; mental illness comes in all forms. I don't know for sure any more than you do. I'm sorry this has become such an issue - I should have liked not to even have mentioned it. Now can we move on and celebrate Malakai's achievement?

Indeed.....we have so much to