Evgeny Kissin, Barbican Hall | reviews, news & interviews

Evgeny Kissin, Barbican Hall

Evgeny Kissin, Barbican Hall

Transports of brilliance in late Beethoven and Liszt from the unruffled master-pianist

Why is music? A child’s question, a great question. One answered by Evgeny Kissin’s piano recital at London’s Barbican Centre last night, where you might want to engage analysis and come up later with answers but what happened was that you left the concert hall feeling more alive, emotions retooled, spirit lightened, range widened. Music is because. Why else would Beethoven compose 32 piano sonatas? What possible purpose of Haydn to write 62 of them? Because.

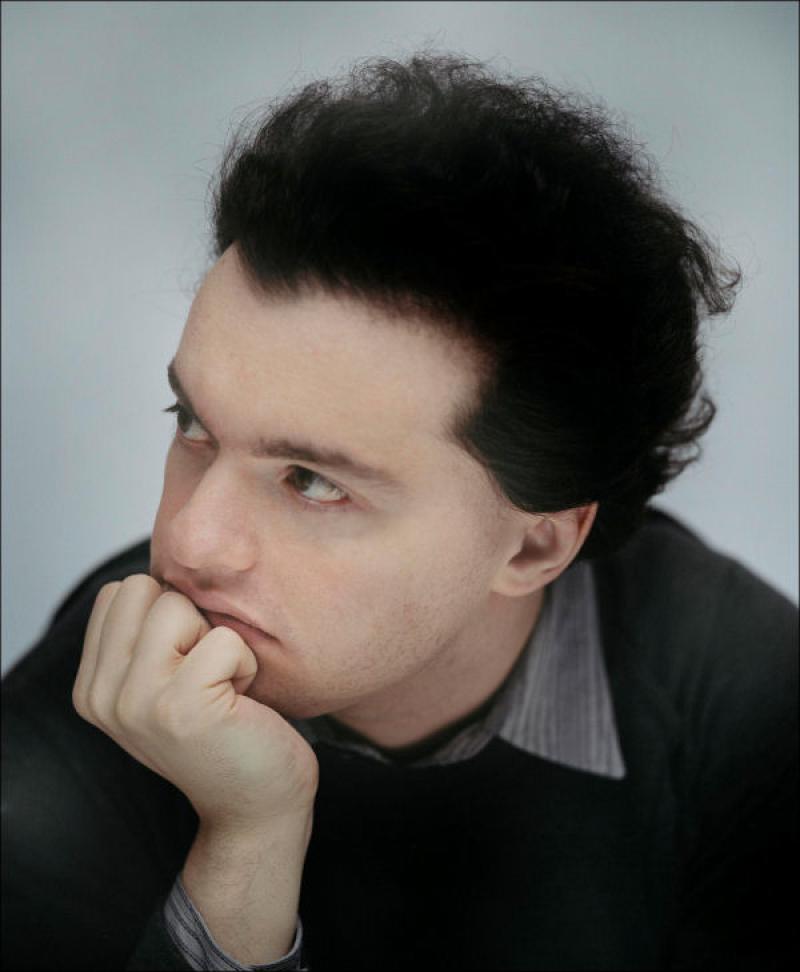

Kissin is 41, which means he has left his child prodigy reputation far behind him and is now maybe midway through his career. I haven’t heard him for a long time, wondering where this reticent, ferociously concentrated personality would take him musically, once the shouting died down over his preternaturally formed Russian technique. What we had last night was a concert of brilliant, fastidious pianism, an atmosphere epic and yet also that of a 19th-century salon, an evening channelling master pianists by a man who has become one of the 21st century’s indubitable master pianists. He plays like someone who could never be parted from his piano, he looks at the public as if he wishes they'd just all go away.

The programme is deeply thought-out (Kissin is playing this programme for dozens of recitals over the next year) and daring, comprising late works by great composers mostly older than Kissin is now - he always seemed an old head on young shoulders. The first half inspiringly coupled Haydn’s 59th sonata with Beethoven’s last: one all temperate 18th-century reason, the other a Byronic 19th-century vision that stares from the chasm to the stars, enlightenment meeting faith.

Kissin took the Haydn with a nice chunky tone and an unhurried steadiness throughout the three movements. Nothing, you felt, could disturb this full, grave pace and this reassuringly well-tempered major key, this young-faced man who sits so controlled at his piano, surrounded by the Barbican Hall’s gorgeously carved linenfold panelling as if this is all there is or should be. Haydn is such a deep composer, so scrupulously alert to the surprise that a single flattened note can bring, that playing like this - quite placid, refusing to be tricky - is satisfying.

Beethoven powers into this new kind of piano like a man possessed with dreams. He flings left and right hands far apart

Then to the gasps and starts of the ferocious first movement of Beethoven’s op 111 sonata, composed more than 30 years after the Haydn, and evidently for an instrument that’s leapt on in every conceivable way. Where Haydn occupies the central zone of the 18th-century keyboard, approaching old age rationally and wisely, not overtesting fingers and ears, the ageing Beethoven powers into this new kind of piano like a man possessed with dreams. He flings left and right hands far apart, from thunderous rumbles and crashes down below to single notes that hammer metallically for attention high above them, or he whips both hands up into the high end for the shimmering, outer-space trills and whispery broken chords that make this sonata so intensely moving to hear, with its deafness to normal acoustic conventions. Kissin played it as if listening to voices inside the storm, with total devotion but in complete control of the journey, feeling the weather, measuring the passage of time, seeing the sun rise on the last day, with those astonishing chimes and twitters like so many church bells and birds at dawn. It takes a tremendous intelligence and visionary stamina to hold this long arc together, a superb, mesmerising experience on every wave-length and one I’m grateful to have heard.

After that we had four Schubert impromptus, which don’t, for me, take well to Kissin’s calculated approach. Four is too many, anyway, but Schubert’s much more delicate fabric, with its repetitious motifs, needs a little more impromptu charm - Kissin’s playing, perfectly textured as it is, is too invulnerable, his pulses just not quite breathing enough.

After that we had four Schubert impromptus, which don’t, for me, take well to Kissin’s calculated approach. Four is too many, anyway, but Schubert’s much more delicate fabric, with its repetitious motifs, needs a little more impromptu charm - Kissin’s playing, perfectly textured as it is, is too invulnerable, his pulses just not quite breathing enough.

But then we were back at what Kissin does with galvanising flair and dynamic empathy, Liszt - transports of pianism with a clarity that floods light through the excitements, so every one comes up thrillingly clean and surprising. Other pianists may like to demonstrate physically that they’re throwing everything they’ve got at Liszt, but Kissin delivers the thrills with no extroversion whatsoever, no waste or distraction. I sat through his playing of the 12th Hungarian Rhapsody feeling ridiculously happy as he exploited every atom of the music’s athleticism, every flash of lightning and thunder, every manic fragment of a jig, head down, all focus on conjuring the magic of Liszt's imagination. A standing ovation quite naturally followed it.

Three salon-style transcriptions scattered chocolates and petits fours around after this rich meal, lush arrangements of Gluck, Schubert and Mozart sweetmeats, overindulgent in calories, but still deliciously confected and spun. The sentimentality that Kissin keeps so deeply subsumed in the intellect and blistering control of his playing here cascaded out, all the more enjoyable for its boyish wistfulness.

- Kissin plays this recital programme at many of his European and US recitals over the next 12 months - see his website for schedule

- Kissin's next British date is scheduled to be 29 December 2013, playing Tchaikovsky's 1st piano concerto under Michael Tilson Thomas and the LSO in London

- More information on the Barbican's current recital programme

rating

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Comments

It was a common sense that

Were the encores not the

The first encore was the

Yes, indeed they were, and