Q&A Special: Actor Bruno Ganz on playing Hitler | reviews, news & interviews

Q&A Special: Actor Bruno Ganz on playing Hitler

Q&A Special: Actor Bruno Ganz on playing Hitler

The Swiss actor, who has died aged 77, was the first to play the Führer in a lead role in German

There is nothing quite like the Iffland-Ring in this country. The property of the Austrian state, for two centuries it has been awarded to the most important German-speaking actor of the age, who after a suitable period nominates his successor and hands the ring on. There were only four handovers in the entire 20th century.

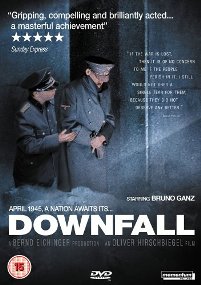

No one put it better than Joachim Fest, the great German historian of the Nazi period: “That really is Hitler.” It was on Fest’s essay about the last days of the Third Reich that the script of Der Untergang by producer Bernd Eichinger is based. Until Downfall (as the film is known in English), Ganz’s best-known role internationally was in Wim Wenders's Wings of Desire, in which he played a ponytailed angel hovering beatifically over Berlin. In Downfall, Ganz gave the world his Adolf Hitler, and he acquitted himself with terrifying aplomb.

The terror was not only in the viperous rages and shrieking attacks of undiluted bile as the Führer harangued his quaking generals (one scene in particular has given rise to an endless stream of often hilarious YouTube mash-ups: see a self-referential example below). It was also in the audacious delivery of a rounded performance in which, against all the known rules of engagement with Nazi history, the murderer of six million Jews was allowed to be seen as courteous to women, fond of his dog, even pathetic in the face of imminent annihilation and suicide. It has, one hopes, put paid once and for all to the endless queue of British actors playing Hitler in English, from Derek Jacobi to Robert Carlyle, Roger Allam to Ken Stott.

The terror was not only in the viperous rages and shrieking attacks of undiluted bile as the Führer harangued his quaking generals (one scene in particular has given rise to an endless stream of often hilarious YouTube mash-ups: see a self-referential example below). It was also in the audacious delivery of a rounded performance in which, against all the known rules of engagement with Nazi history, the murderer of six million Jews was allowed to be seen as courteous to women, fond of his dog, even pathetic in the face of imminent annihilation and suicide. It has, one hopes, put paid once and for all to the endless queue of British actors playing Hitler in English, from Derek Jacobi to Robert Carlyle, Roger Allam to Ken Stott.

Set in and around the moral vacuum of the bunker, Downfall featured the first portrayal of Hitler at the heart of any German drama. No wonder the country’s most expensive film since Das Boot plunged the nation into an orgy of Teutonic agonising over the propriety of putting the human face of Hitler on the big screen. One question rang out above all. Although dramatically rational, is it ethically feasible to portray a genocidal monster as a human being? When I met Bruno Ganz in Berlin - in a hotel in Potsdamer Platz, newly restored from the ravages of war - I put all these questions to him. This is a full transcript of the fullest interview he gave to a British journalist about playing Hitler.

Downfall mash-up: Hitler is informed he is Bruno Ganz:

JASPER REES: Did living in Berlin help you making this film?

BRUNO GANZ: Oh yes. Because I know what Germany is. I know somehow what Germans are. I feel close to them and I have no problem to be a German. I’m OK when I’m here. But it helped me also that I am not German because I could put my passport between Hitler and me. And I have not this kind of problems like a lot of my German friends have, questioning their parents or grandparents what they did do in that time. That’s not because in Switzerland nobody was in this way involved in Nazis. But it’s one thing to read books and to learn, get some knowledge about history by reading, or to live in a country. And so I think this was very important.

Is it possible to say how you prepared?

It’s quite easy. I was told there was very little left – newsreel or filmed stuff - and even pictures were not taken: he didn’t allow it any more. At the end. I don’t know how long - at least the last two or three months. So the real source was what the witnesses said and a lot of them wrote books later.

But there is one bit of extant film from that period in which he is seen with the Hitler Youth.

But there is one bit of extant film from that period in which he is seen with the Hitler Youth.

Decorating his kids. That’s the one left (pictured left).

What did that tell you?

Well, not much. It told me that he looked like I thought he would and that he was really destroyed, he was somehow fragile. I had rather pity with him. And I learnt that he really had Parkinson’s. His hidden left hand on his back and if you had not known you would not have been aware of it but I knew it so I saw how it was trembling or shaking - a kind of tremor.

How did you get an impersonation of a tremor?

That’s what actors do. You ask a doctor if he can organise that you see patients with Parkinson’s and you sit there for hours and watch. That’s what you do.

Did you have to pretend to have it when visiting the doctor?

I did it for myself because I felt really somehow ashamed. I was watching these people and I know how it feels to be watched all the time and they tried to hide it because they felt that someone was watching them. So I started to become like them.

Was it difficult to say yes?

It took me about a month. My first reaction was I was interested immediately because, as actors say, it’s a challenge. It was really one. But I thought, you know, you are tackling something quite difficult and if it’s going to be seen by many people throughout the world you will be identified with the one who played Hitler and that’s not easy. But I was not scared to get closer to that decade of the time historically and I was not scared to get close to Hitler. I thought I might discover that Hitler was not really a big man… but the difficulty is to deal with that image, that icon, that kind of myth that Hitler still is for everybody. I think even the problem people have saying I am humanising. Just the term is funny. That means to me that there is still a huge gap… they need an intact icon of the evil itself. I don’t know what evil itself is. And I who knew nothing about Hitler in his last two months, very little, and who learnt who he was – people telling me in these books what they saw and his behaviour and what he was like and what they felt and since it’s a lot of people, after all this somehow your imagination starts to work and you get quite a clear image of such a person. So it was not easy to say yes.

Did you talk to Joachim Fest

Fest was very important for me. Fest talked about Hitler. I think that was the most important thing I read. He’s not just portraying Hitler as a person or psychological things or where he came from. His relationship with the German people, that’s what interested him, and that’s the same thing that interested me most. I thought it was the evil Hitler who got in such a high position. It was the German people who supported this man.

Did he have charm?

Did he have charm?

I wouldn’t say charm. Charisma. Some say he was like a chameleon. He could change colours and behave in this way or that way. I think what people needed desperately and what he gave to them – it seemed that he would be the only one who was able to give it – was they felt very humiliated after the First World War and they needed someone who gave them back their dignity. This is a very limited English word but it’s true. Some sort of humiliation. Every speech the first eight years is about the Versailles Treaty and always it ends with him promising people that he will be the saviour of the German people. He was the only one in Germany – in the beginning they did not understand – that when he said something he did it also. They could not believe it. Because a politician was not supposed to be the one who does what he announces to do. The countries around Europe just underestimated him.

The voice that has come down to us is the speech-making voice but it’s not the voice that you are doing for most of the film. There are some moments in the film where Hitler goes absolutely mad with his generals but he often speaks very softly. Where did you find that?

I was lucky or my producer was smart. He sent me a little tape, seven minutes recorded secretly in I think 1942, maybe in Helsinki. He’s talking to a Finnish diplomat. And he did not know that he was recorded. So he is very calm.

What’s he talking about?

Well, his army. "Our army is not a winter army. Now we made these real experiences on the Russian front because when it’s winter there our equipment is not for winter. I just didn’t realise that we are a summer army." As very often he is quite stupid. He was what we call an autodidakt. He believed in himself very strongly so he was the one who knew everything about everything. This is boring, because he knew a lot about ammunition and some about the army and he was an artist, he had a certain sense for surprising things. And that made him very successful, because they did not expect what he did and what he decided. He was a gambler as well. And he did things others would not have dared to do. That was his quality.

What did you get from this voice?

I liked it because it was deeper, lower, than his screaming shouting voice. You can hear him during his speeches. And it was completely relaxed. The voice sounds… I liked it.

He sounds like a human being?

He sounds as well like a human being in another speech I heard. That’s about 30 minutes. He is answering a telegram Roosevelt sent to the Germans and he replied in a 20-point telegram. He read this to an audience in the German Reichstag. He tried to be witty, he tries to be ironic and the applause is huge. At that time he was king of Germany and he would do what he wanted and people were always pleased by what he did. But his attempts to be witty in an English sense, it’s just terrible. But he is not shouting there. He is convincing enough there with his irony as he thinks and so he keeps his voice on a level you are not scared of. You can listen to him. But it’s not as intimate as it is with this seven-minute tape with this diplomat. That’s really very, very private between those two people.

Does he have an accent?

Does he have an accent?

I can hear very clearly that he came from Austria. That he is not German. It’s a mixture between this Austrian German and a very military German that he learned afterwards. He had what you can still see in Vienna. In French it would be courtoiser les femmes (pictured: Ganz with Juliane Köhler as Eva Braun). Soft manners and kissing hands. That’s very Austrian. He was quite good at that. His behaviour towards women was not bad. They were very pleased in Germany because their own men were not able to do this.

Did the theatre artist in you address the issue of his fascination for Wagner?

I think he got very early deep, deep, deep in Wagner’s work, by seeing as a boy in Linz Wagner’s operas. And he was excited about that, he felt he was really a part of the Wagnerian world and imagination. Also unfortunately other things that Wagner had in mind as his anti-Semitism. I think he was devoted to all this show and theatre and actors and opera singers. He had a feeling of that. He was an artist. He was a failure because he had no talent but he was an artist. He had a sense for it - maybe for the cheap aspect of it but he had it, and it helped him because he used it.

He was a sort of actor?

I think he could imagine being something to the extent of becoming it. As we would say, auto-suggestion. His imagination was very strong. He could move himself to be something. This is close to being an actor, yes.

Did you have to do the same thing in order to be him?

Maybe. That’s not bad. But with me it’s more technical. I don’t have the strong beliefs he had. He was really a believer. He believed in what he wanted to do. And his hatred for the Jews was really incredible. I never found out what was really the point of departure. Why this was is completely hidden.

The film is not about this though. The Jews are mentioned only once.

The film is not about this though. The Jews are mentioned only once.

I know. Talking to Speer (pictured: Ganz with Heino Ferch as Albert Speer) he mentions it once. That’s something to ask the writer of the script, not me.

How long did you spend researching, as it were, in the bunker?

I was quite prepared when I came. Seven or eight weeks - four months' reading, watching patients and listening to this tape and then I asked them to provide me with a kind of coach. I wanted an Austrian actor for that region and he came to Zurich and he helped me.

Was it the first time you have impersonated a historical figure?

That scared me most. I’ve never done this because I prefer to invent people and not do an imitation. I am very reluctant to do that. Once they wanted me to play Einstein and I was deep in preparation but then I stopped, I couldn’t do it. This was quite long ago: 15 years ago.

Once you were in the actual bunker, did you become inhabited by the character? Were you able to step out of him when the director called "cut"?

This was part of my preparation. You have to construct a wall or an iron curtain that when it’s a wrap it’s gone. I don’t want to spend my evenings at the hotel and dinner with Mr Hitler at my side. I really managed that. I’m not a method actor. Somehow I tried to get as close as possible but not at night or outside the studio.

Did people react to you in a different way?

They did. They were scared or they just couldn’t believe it because the resemblance was quite big. And I happened once to cross a street in Petersburg which had suffered very, very badly – three million people died of hunger because Hitler’s blockade. I had to shoot there for three days. My first shooting day I went from the trailer across the street to the set which was the old Nazi embassy and people stared at me. I was very ashamed and I felt terrible. So I was glad to shoot this in a studio. We had no people from outside. We were not on the street. And the people working in that studio were from our crew.

What did you do to your face?

Nothing. Nothing.

The eyes?

No.

No contacts?

No.

I was curious to know what height you would be. You seem very small in the film.

Nothing. That happens. It seems to me that he was quite short. Especially when he got old. He was 56 when he died and he looked about 80 and he was completely destroyed.

Was it a surprise to discover that you looked like him?

Yes it was. But in a Russian play about Kronstadt - a revolution by Russian marines against Lenin, but from the left - I was one of these sailors. We were about 20. Each of us were dressed in the same way in a sailor’s cap and the same kind of rifle. So that you could distinguish people I had a moustache. Others had a real one so I said, "OK give me a small one." And that was the first time I said, "Jesus Christ, you look like Hitler." So I was not completely surprised. But I was surprised with the addition of the wig how far it went. I was scared just for two or three seconds. Then I was actor enough to say, "That’s OK, that will help. Even if you are bad as Hitler still you’ll look like him."

What is the best compliment that has been paid to you?

I got a letter from David Hare. That was very, very nice. He liked it a lot. A big, big compliment. Fest was good. And I got one from someone I don’t know but who wrote to me when he learnt in the newspaper that I would be the one to play Hitler. He wrote me a letter saying, "Don’t fall into the trap of chewing the carpet. Just avoid that. Because I was close to that man and I knew him and that’s not him." He saw the movie and he wrote me a second letter saying I came very close to the real person. So I can live with that. I know his name, I know that he is a doctor. He never occurred in lists from people close to him. He must have been in the health department and must have seen Hitler several times.

One of the most significant moments in the film is in the very first scene (pictured) when several young applicants for the post of Hitler's secretary are waiting for him to show his face round the door. Those ladies are in effect us. They have this overpowering fascination with this figure and we have the same guilty fascination. We can feel his charisma even through someone who is not him. Were you aware coming through that door that that was what you were playing?

One of the most significant moments in the film is in the very first scene (pictured) when several young applicants for the post of Hitler's secretary are waiting for him to show his face round the door. Those ladies are in effect us. They have this overpowering fascination with this figure and we have the same guilty fascination. We can feel his charisma even through someone who is not him. Were you aware coming through that door that that was what you were playing?

That’s what I wanted. I was very, very happy when I saw that sequence for the first time because it worked. It’s the period he is strong and the audience should be aware that he was really not stupid and that he was a powerful man. People say fanaticism but even fanaticism is fed by something. Sometimes I felt he would have been the founder of a new religion or something like that. His power came from – now today we would use a term like spiritual sources – you have to be careful with that but somehow it got close to that.

Did you feel pity for him?

Sometimes at the end I thought, you are such a stupid guy. Just stop it. Go home and leave it. You should now realise that you did the wrong thing. It’s all finished. You wanted to rule the world with your race, and now you’ve destroyed the bourgeoisie as a class, it went even home to Germany, you destroyed your own people. And you did one crime that Germany will never never never never get rid of. A genocide with an industrial way of doing it, that’s too much. This makes you. You are out of the human community with that. Nobody can take that. Nobody can even explain. Not even he himself could.

And yet he is a human being.

Of course he is. What else should he be?

In a lot of the discussion of the film he is talked about not as a human being but as a monster. It strikes me as a stupid thing to say.

I accept that from Jewish survivors. They can talk like this, and I would say, "OK, we are not going into details, respect and let’s stop here. I don’t want to start to argue." But I don’t accept that. It is stupid.

Did you speak to Jewish survivors?

I met a lot of them in the region of Los Angeles. They are very fair. Incredibly fair. Of course they ask you but they are listening. To me they appeared very fair. I was amazed.

Is this one of the most important roles of your life?

I think so yes.

The film's direct Oliver Hirschbiegel said you had to discover the evil within yourself.

Coming up with terms like "evil" and "good" makes me nervous because I don’t know what it is. And so I tried to split it or to surround it. Maybe I am searching for a gap or a hole to fragment. Evil, I don’t know what it is. It makes no sense. But I know what he means.

Ganz as Hitler remonstrates with the military top brass:

That sense of evil seems mostly to show in his scenes with the generals.

He was very successful when he attacked the French because he had a plan that all the generals said was nuts. And he did it because by then he was the Führer and they had to do it. He overran France within two weeks. It was just incredible. In two weeks France became the property of Germany and that made him so big that they didn’t dare criticise what he wanted to do. And part of that he saved in the bunker. "There’s the 4th Army and there’s another army." He doesn’t really believe it but it’s the same thing. He is able to... [Ganz mimes pulling up the top of his head]. We have a famous figure called the Baron von Münchhausen, the one riding on cannonballs. In the mud he takes his hair and pulls himself out of the mud. That’s what Hitler was able to do. By grabbing his hair.

Was there any part of this role that was enjoyable? Or are you not allowed to say that?

I think I am not allowed to say that. I could partly understand him. His anger he had when two of his own friends (who were never really friends) - Himmler and Goering - when they left him, he felt betrayed, because they started with him very early on the streets of Munich. They were really the hardcore of the first Nazi group and in 1945 he gets this telegram saying if he doesn’t answer before 10 o’clock they will take power. He really got very upset and I could understand that. But it’s unpleasant. His relationship with Eva Braun ...

Do you think they had sex?

Maybe once or twice. I think he was able and he might have done it five times in his life.

Goebbels says in the film, "Gentlemen, in a hundred years from now they will make a wonderful colour film about the terrible days we are living through now. Wouldn’t you like to have a part in this film?"

He was a smart guy. He was really smart.

Did he understand that Nazism was theatre?

He understood that it was partly show business. He was really intelligent and he manipulated the media and he was very, very cynical. At the same time he was a Nazi believer. No doubt. He would have understood that evil can fascinate people two, three, four, five hundred years later.

You were born two months before the invasion of the Soviet Union. Did you grow up with stories crossing the border?

I was not really aware. I remembered the absence of my father because he had to do military service for four years, which was very unusual in Switzerland. You do service for three weeks a year, which is quite different from a normal army. I remember that once my mother was very excited because they found in the garden pieces of metal which seemed to be from the wing of an American bomber who confused Zurich with Stuttgart. I think at some time I must have heard Hitler’s speeches but I’m not sure. My mother was talking about how we had to suffer in Switzerland because he did not have full access to bananas and oranges. Just ridiculous things. I don’t know what war is, not really.

When did you do your last military service?

When I was 50. Then you are free. It was one of my best days. I hated the Swiss army.

Did they give you a knife? That’s all we know about the Swiss army.

There is not much more to know.

Bruno Ganz, 24 March 1941 - 16 February 2019

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Comments

...

...

...

I have to correct the great

I, my partner and son watched

Hitler is recorded using his