The Magic Flute, Garsington Opera | reviews, news & interviews

The Magic Flute, Garsington Opera

The Magic Flute, Garsington Opera

Garden opera in the deerpark demands wit as well as magic

Tamino and Pamina, in Mozart’s great masonic opera, go through fire and water, as well as trials spiritual and emotional, before achieving their sunlit triumph at the end of it all. They would have sympathy with Anthony Whitworth-Jones and his Garsington Opera team in what must have been quite as frightening a battle to locate, plan, design and build their new pavilion on the Getty estate at Wormsley, near Stokenchurch on the M40, within barely more than a year.

I ended my review of their final production (Britten’s Midsummer Night’s Dream) at the manor last June by reporting that the company needed three million to keep afloat. It became three and a half million, but they got it. And the result is a triumph no less great than Mozart’s lovers’: a superb new theatre in a parkland setting as magical as any you could imagine this side of – where? Glyndebourne? Grange Park? Iford? Garsington Manor itself?

There’s no serious comparison. Those places have their beauties, but none of them offer anything remotely like the great sweep of parkland, lake and woods that makes up for the admittedly rather dull house and gardens at Wormsley. The new demountable theatre surveys this landscape like some modern equivalent of a Beckford folly: it both challenges and defines it, both clashes and harmonises with it. As you leave in the fading light of a June evening, picking your way along the wood-chip roads or through the long meadow grass, the brightly lit pavilion gleams out across the park like a stage-set in its own right, with a wing of softly backlit marquees stretching out along the perimeter. Pure enchantment! (But pray it doesn’t rain…)

Of course, the outside of such a theatre is all very well for picnics, but it’s the inside that matters for opera buffs, of whom there were plenty, in among the great and the good, the makers and shovers, this opening night. It seems to me that Robin Snell, the architect (who also worked on the new Glyndebourne opera house back in the Nineties) has got this right as well. Unlike the old lean-to theatre at the manor, which you always felt might get whisked away by a modest gale, at Wormsley he’s designed a proper four-sided theatre, very much open to the evening sun (so a fair challenge for directors of operas like The Magic Flute, or for that matter A Midsummer Night’s Dream, where darkness is required), but solid and comfortable and permanent-feeling – deceptively so, since it will in fact be put up and taken down each season.

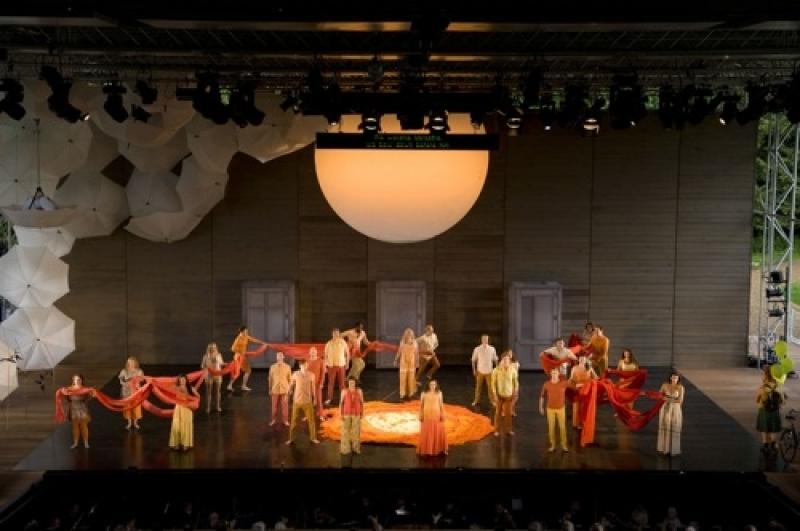

The stage is big and open – no proscenium, no wings, no hiding place at all other than what the director might put on it. Mozart’s three doors (unlabelled) occasionally trundle forward off a plain, timber-clad back wall, which is presumably part of the building rather than the set, though one can’t be sure. Characters come and go through trap doors. Tamino’s flute and Papageno’s noose drop down from the visible flies gantry; the three boys float across worryingly high up in an upturned parasol engaged in an understandably desultory pillow fight (parasols and umbrellas are iconic for director Olivia Fuchs in this work, as they were for Dominic Cooke at WNO, though quite why is a puzzle, unless they’re to keep off the Sarastran sun).

One of the wittiest, most brilliant stage entrances I can remember, and one which set up the evening as a kind of domestic pantomime

Papageno appears on a bicycle and rides out of the theatre, right round the outside front-of-house, and back in on the other side of the stage, all during the orchestral introduction to his birdcatcher’s song: the death of mystery, perhaps, but one of the wittiest, most brilliant stage entrances I can remember, and one which set up the evening as a kind of domestic pantomime, making the best of mildly straitened circumstances: a spectacular best, it must be added, climaxing in the unnervingly real fire of the first ordeal and the comically bathetic rain shower of the second that will – on wet evenings (which this one, by divine intervention, was not) – unite cast and audience in shared misery and shared hope.

Fuchs’s staging, performed in English (Jeremy Sams) and with much-trimmed dialogue, has its pointless-seeming digressions: why does Tamino enter pursued not by a serpent but by a bevy of black-clad binge-drinking tarts, and, more wasted than scared, light a fag (another of Fuchs’s icons – Papageno even offers the front stalls a puff)? Why is the Speaker (Benjamin Bevan) a bookish philosopher in a tweed jacket but the “beauty and wisdom” of the final chorus a teenage rave? Why are the animals Tamino charms with his flute replaced by Tamino lookalikes, similarly (and, by the way, very unprincelily) clad in jeans and flowered white shirts (very deep, this, but I can’t see down it)? Why, finally, are these philosophers of wisdom, nature and reason so rough, always pushing people over (a habit that proves catching)?

“Why? Why? Why?” to quote the three ladies when they find Tamino in Sarastro’s temple. Perhaps, like Tamino, we shouldn’t ask, but instead relish the speed and invention of this constantly entertaining production, a more than worthy opener for a marvellous new opera house, and, with hardly an exception, immaculately sung and played.

Not much question that the show is stolen by William Berger’s kilted, mohicaned Papageno, no silly feathered yokel with a birdcage, but a savvy urban hedonist bested by subtler, if not wiser, types (after all, he gets the girl: Ruth Jenkins, excellent; Sarastro is stuck with “lofty purpose”). Berger is also a deft, musicianly baritone, and a communicator who has the audience, if not the birds, eating out of his hand. Opposite him Robert Murray (pictured right with Berger) is a mildly flabby Tamino, but a fine, elegant Mozart tenor; and Sophie Bevan is the most natural Pamina imaginable, both in voice and stage presence.

Not much question that the show is stolen by William Berger’s kilted, mohicaned Papageno, no silly feathered yokel with a birdcage, but a savvy urban hedonist bested by subtler, if not wiser, types (after all, he gets the girl: Ruth Jenkins, excellent; Sarastro is stuck with “lofty purpose”). Berger is also a deft, musicianly baritone, and a communicator who has the audience, if not the birds, eating out of his hand. Opposite him Robert Murray (pictured right with Berger) is a mildly flabby Tamino, but a fine, elegant Mozart tenor; and Sophie Bevan is the most natural Pamina imaginable, both in voice and stage presence.

Kim Sheehan is an utterly brilliant Queen of Night, costumed like a panto demon but angelic in her upper register (we can forgive her a couple of missed top Fs: she gets most of them, so perhaps the misses were to remind us how hard it all is). Iain Paton is a funny and stoical leather-jacketed Monostatos – tactfully white (though oddly Fuchs doesn’t stint on the other non-PC aspect of Schikaneder’s libretto, its condescension towards women, which just happens to be embalmed, like the anti-Semitism of A Merchant of Venice, in one of the most sublime of all masterpieces). Evan Boyer’s Sarastro is suitably solemn, dignified, unexpectedly youthful, not always completely projecting his lowest register and tending to favour oratorian pronunciation: “comparsion”, “harpiness”, etc.

A strong team of ladies, two fine armed men, and three rather tall but small-voiced boys, towering over the diminutive Sophie Bevan: too many individuals to name. And a vigorous, athletic, youthful chorus, also required sometimes to act as scenery, with or without umbrellas.

It should be said that, among his other successes, Robin Snell has produced what, from row C of the stalls, sounds like a near-perfect acoustic. Its great virtue, curiously rare in opera houses, is that it favours the voices, but without – if this isn’t too much of a paradox – disadvantaging the orchestra. Martin André’s Mozart is brisk, alert, inclined on occasion to push the voices, but never to overpower them, and nicely balanced instrumentally. The opera was preceded by a fanfare, specially commissioned from Jonathan Dove, which oddly enough did not sound well in this space. This may have implications for bigger orchestras here. Or it may just be that Dove misjudged – or simply didn’t know enough about – the theatre he was writing for.

- The Magic Flute at Garsington Opera at Wormsley until 5 July

- Find out about Garsington Opera at Wormsley

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Le nozze di Figaro, Glyndebourne review - perceptive humanity in period setting

Mostly glorious cast, sharp ideas, fussy conducting

Le nozze di Figaro, Glyndebourne review - perceptive humanity in period setting

Mostly glorious cast, sharp ideas, fussy conducting

Fidelio, Garsington Opera review - a battle of sunshine and shadows

Intimacy yields to spectacle as Beethoven's light of freedom triumphs

Fidelio, Garsington Opera review - a battle of sunshine and shadows

Intimacy yields to spectacle as Beethoven's light of freedom triumphs

Dangerous Matter, RNCM, Manchester review - opera meets science in an 18th century tale

Big doses of history and didaction are injected into 50 minutes of music theatre

Dangerous Matter, RNCM, Manchester review - opera meets science in an 18th century tale

Big doses of history and didaction are injected into 50 minutes of music theatre

Mazeppa, Grange Park Opera review - a gripping reassessment

Unbalanced drama with a powerful core, uninhibitedly staged

Mazeppa, Grange Park Opera review - a gripping reassessment

Unbalanced drama with a powerful core, uninhibitedly staged

Saul, Glyndebourne review - playful, visually ravishing descent into darkness

Ten years after it first opened Barrie Kosky's production still packs a hefty punch

Saul, Glyndebourne review - playful, visually ravishing descent into darkness

Ten years after it first opened Barrie Kosky's production still packs a hefty punch

Così fan tutte, Nevill Holt Festival/Opera North review - re-writing the script

Real feeling turns the tables on stage artifice in Mozart that charms, and moves

Così fan tutte, Nevill Holt Festival/Opera North review - re-writing the script

Real feeling turns the tables on stage artifice in Mozart that charms, and moves

La Straniera, Chelsea Opera Group, Barlow, Cadogan Hall review - diva power saves minor Bellini

Australian soprano Helena Dix is honoured by fine fellow singers, but not her conductor

La Straniera, Chelsea Opera Group, Barlow, Cadogan Hall review - diva power saves minor Bellini

Australian soprano Helena Dix is honoured by fine fellow singers, but not her conductor

The Queen of Spades, Garsington Opera review - sonorous gliding over a heart of darkness

Striking design and clear concept, but the intensity within comes and goes

The Queen of Spades, Garsington Opera review - sonorous gliding over a heart of darkness

Striking design and clear concept, but the intensity within comes and goes

The Flying Dutchman, Opera Holland Park review - into the storm of dreams

A well-skippered Wagnerian voyage between fantasy and realism

The Flying Dutchman, Opera Holland Park review - into the storm of dreams

A well-skippered Wagnerian voyage between fantasy and realism

Il Trittico, Opéra de Paris review - reordered Puccini works for a phenomenal singing actor

Asmik Grigorian takes all three soprano leads in a near-perfect ensemble

Il Trittico, Opéra de Paris review - reordered Puccini works for a phenomenal singing actor

Asmik Grigorian takes all three soprano leads in a near-perfect ensemble

Faust, Royal Opera review - pure theatre in this solid revival

A Faust that smuggles its damnation under theatrical spectacle and excess

Faust, Royal Opera review - pure theatre in this solid revival

A Faust that smuggles its damnation under theatrical spectacle and excess

Comments

...

...