Dorothea Tanning, Tate Modern review – an absolute revelation | reviews, news & interviews

Dorothea Tanning, Tate Modern review – an absolute revelation

Dorothea Tanning, Tate Modern review – an absolute revelation

An artist with a unique voice eclipsed by her famous husband

Tate Modern’s retrospective of Dorothea Tanning is a revelation. Here the American artist is known as a latter day Surrealist, but as the show demonstrates, this is only part of the story. Tanning’s career spanned an impressive 70 years – she died in 2012 aged 101 – but as so often happens, she was eclipsed by her famous husband, German Surrealist Max Ernst.

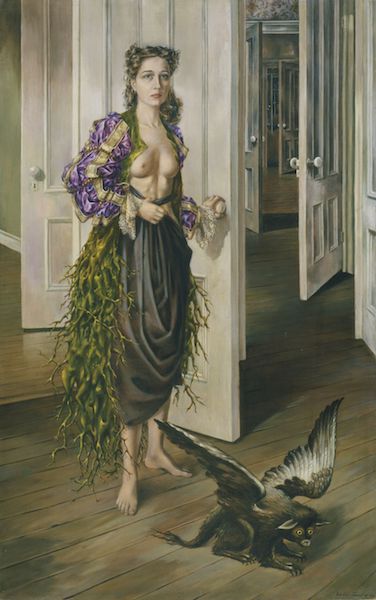

They met in New York; he was scouting for artists to include in an exhibition staged by his then wife, Peggy Guggenheim. On the easel in Tanning's studio was Birthday, 1942 (pictured below right) a newly finished self portrait. The story goes that Ernst was so entranced by the painting that he fell in love with its author, and you can see why.

Tanning was a phenomenally good draughtswoman, able to conjure an imaginary scene in minute and convincing detail. Inspired by painters like Salvador Dali and René Magritte who were renowned for portraying dream-like imagery with hyper-real clarity, she was far from being a mere follower. She quickly developed her own vocabulary.

Inspired by the teachings of Freud, the Surrealists were keen to bypass the rational mind and gain access to the unconscious. In Tanning’s paintings, open doors and empty corridors function metaphorically as portals to the hidden realms. She never shows us what lies beyond these eerie spaces, but various weird creatures seem able to cross the threshold from the murky depths of the psyche into everyday reality.

Inspired by the teachings of Freud, the Surrealists were keen to bypass the rational mind and gain access to the unconscious. In Tanning’s paintings, open doors and empty corridors function metaphorically as portals to the hidden realms. She never shows us what lies beyond these eerie spaces, but various weird creatures seem able to cross the threshold from the murky depths of the psyche into everyday reality.

In Birthday, for instance, a fury little monster with large wings sits at her feet. There she stands – bare foot, bare breasted and beautiful – her hand resting on the handle of a door that opens onto infinitely receding chambers. She wears a twiggy skirt bedecked with tiny female nudes that, like the nymph Daphne, are being transformed into trees. Her trance-like gaze and the presence of her familiar suggest supranormal powers; she is inviting us to accompany her into the unknown, and it will be a bumpy ride.

Tanning was born in Galesburg, a small town in Illinois where, she said: “nothing happened but the wallpaper”. To counter the tedium, she read Gothic novels and acquired a taste for the uncanny, a feeling that pervades her early work. In Children’s Games, 1942 two wayward girls are ripping off the wallpaper to reveal the nastiness hidden beneath its bland surface.

Family life, it seems, was not all roses. Family Portrait, 1954 shows a young woman sitting demurely at a table covered in a white cloth. Behind her, the ghostly figure of her unsmiling father merges with the wall, as though the very fabric of the house is suffused with his domineering presence. The creases in the tablecloth indicate that it has been folded in a drawer. “There was a long dining room table,” Tanning recalls of her childhood, “that on Sunday, especially when the pastor came to dinner, got covered first with a pad and then the great gleaming white tablecloth. They shook it out and laid it down, smoothing out the folds that made a gentle grid from end to end. The grid surely proved that order prevailed in this house.”

Some 20 years later, the same tablecloth appears in Notes for an Apocalypse, 1978 (main picture). This time a corner has been lifted to reveal a Rubenesque nude arching backwards under the tumbling weight of an older man, while a doll-like child clings to her leg. Tanning was reluctant to analyse her pictures, but this highly sexualised scene suggests a young woman torn between childhood innocence and adult awareness, amid the resurgence of suppressed desires.

She had long since abandoned the hyper-realism of her Surrealist phase for a looser, more spontaneous way of working that allowed the image to materialise through the process of painting. “In the first years”, she wrote, “I was painting on our side of the mirror – the mirror for me is a door – but I think I have gone over to a place where one no longer faces identities at all.”

In 1957, the couple moved to France where these freer, more fluid paintings began to emerge. As you peer into the painterly maelstrom of Dogs of Cythera,1963 (pictured above) myriad body parts come into focus. In Tango, 1977 a couple performs a naked dance while seeming to float on clouds of euphoria while in Useless, 1969 female bodies intertwine in an orgiastic whirl of sporadic colour. They are unlike anything I can think of being done at the time, yet these paintings look familiar, probably because they prefigure by some 30 years work by contemporary artists such as Cecily Browne (with their teaming multitudes) and Jenny Saville (in their relish of female flesh). Even more of a surprise are her soft sculptures. Begun in the mid-1960s they not only anticipate Louise Bourgeois, but also predate Sarah Lucas’s stuffed tights by some 20 years. They are like 3D manifestations of the women in her paintings; Reclining Nude, 1970 could have escaped from Dogs of Cythera; with its multiple limbs, the naked form resembles a giant squid. Locked in a clinch with a headless gorilla, the headless woman in Embrace, 1969 resembles the nude in Notes for an Apocalypse. This unlikely couple appears again, bursting through the wallpaper of Hotel du Pavot, Room 202, (pictured above) a claustrophobic installation made by Tanning in 1973 in which the nightmares that haunt her early paintings are given fleshy, sculptural life in a dingy hotel room.

Even more of a surprise are her soft sculptures. Begun in the mid-1960s they not only anticipate Louise Bourgeois, but also predate Sarah Lucas’s stuffed tights by some 20 years. They are like 3D manifestations of the women in her paintings; Reclining Nude, 1970 could have escaped from Dogs of Cythera; with its multiple limbs, the naked form resembles a giant squid. Locked in a clinch with a headless gorilla, the headless woman in Embrace, 1969 resembles the nude in Notes for an Apocalypse. This unlikely couple appears again, bursting through the wallpaper of Hotel du Pavot, Room 202, (pictured above) a claustrophobic installation made by Tanning in 1973 in which the nightmares that haunt her early paintings are given fleshy, sculptural life in a dingy hotel room.

A second woman thrusts her naked belly through the wall, while a woman’s hand waves in desperation from behind the chimney breast. Beneath them, slumped across the table is a corpse-like form; the chair has grown an elongated limb and a Hieronymous Bosch-style monster slithers down the chimney. The title of this house of horrors recalls a pop song about Kitty Kane, a gangster’s moll who poisoned herself in a Chicago hotel; without being histrionic, the installation makes palpable her desperation and fear.

Dorothea Tanning emerges from this show as an artist with a unique voice; not only did she continue to explore and develop throughout her long career but produced work that anticipates many of the ideas still in currency today. It's shocking that she could have been overlooked for so long.

rating

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Comments

Of course Dorothea Tanning

Of course Dorothea Tanning was overshadowed by Max Ernst, but there is, to my mind, a reason: she isn't a first-rate artist and visiting the Tate Modern show last week, not only left me cold and at times bored, but surprised that she should get the full "great artist", (albeit neglected by an undoubtedly patriarchal art history world) treatment. This is a major show, but does she deserve it? I was hoping to have my mind blown, and to discover a truly original and interesting artist, but she demonstrates all the worst features of surrealism's paradoxical literalism: dreams upon which the full light of reason has been shone, rather than presented with something like subtlety or poetry. Some of her human figures are so kitsch as to be ridiculous: rosy cheeked young women that could have stepped right out of an amateur painting sold on the Bayswater Road. The later more expressionist work lacks, to my eye and mind, any conviction, as if she were endlessly searching for a visual language thart would do justice to her vision, and yet never finding it. The sculptures are interesting, though, but reminded me too much of the magnum opus of Louise Bourgeois, her contemporary. Next to Bourgeois, who ranks along with (if not above) the very best artists of her generation, Tanning's work seems to miss the mark.