In a constantly challenging output of ballets, the remarkable choreographer Kenneth MacMillan produced nothing more upsetting than his last, The Judas Tree. Baldly, it portrays gang-rape, double murder and suicide among a nasty bunch of men on a building site. Brian Elias’s music slashes and bashes frighteningly around the listener’s head; Jock McFadyen’s gritty Canary Wharf set is the epitome of everything sinister about building sites; and above all MacMillan’s choreography takes sexual confrontation to a pitch even he had never matched in the extremes of his uninhibited imagination.

He said in an interview at the time: “This ballet is my subconscious at work... I had to wait for it to happen in the room. There are things in me that are untapped and that have come out in this ballet that I find frightening. This is a dark one.” In the days after its premiere, even people with time to reflect found it hard to get past its shockingly literal violence to more symbolic, layered explanations of its ideas.

But 18 years have passed - almost a generation - and when it’s revived at the Royal Ballet next week The Judas Tree may well be time-warping into an era that at last understands it as a concentrated “psychological fable”, as the Observer critic Jann Parry found it when she watched it in 1992. Her review struck a chord with MacMillan, and her recent biography of him, Different Drummer, expands on the idea that this was a piece of modern theatre exploring in balletic terms the opposition of masculine and feminine principles, rather than some attempt at a contemporary representation of all-too-common sexual abuse.

In fact, the impact of The Judas Tree is probably more productively understood as a happenstance - a collision of choreography, music and design that generate their own combustion, because three people were all tuning onto the same creative wavelength. Jock McFadyen, the Scottish painter, happened to live by the Canary Wharf building site, with its teeming men in yellow vests, and wanted to portray its shadowed resonances on stage. Brian Elias wrote his apocalyptic score at MacMillan’s request, only loosely on the theme of betrayal. MacMillan was already firmly in harness to his own longstanding personal preoccupations when he at last got the music in the orchestrated form that he could use.

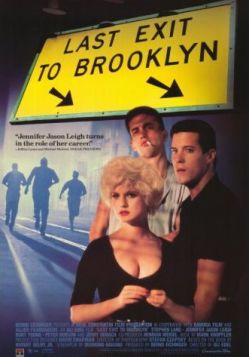

MacMillan’s influences were a tumble of current media events and impressions - the constantly televised seven-week stand-off of Chinese students in Tiananmen Square, with the sole T-shirted lad facing the tanks; a 1990 film, Uli Edel’s Last Exit to Brooklyn, in which men behave with great violence towards women as if substituting loathing of their “feminine” compassionate side; and, significantly, a residual association with the word “betrayal” which brought into his agnostic imagination the intense psychological drama of Judas’s betrayal of Christ, and the ambivalent place in Christ’s story of Mary Magdalene.

MacMillan’s influences were a tumble of current media events and impressions - the constantly televised seven-week stand-off of Chinese students in Tiananmen Square, with the sole T-shirted lad facing the tanks; a 1990 film, Uli Edel’s Last Exit to Brooklyn, in which men behave with great violence towards women as if substituting loathing of their “feminine” compassionate side; and, significantly, a residual association with the word “betrayal” which brought into his agnostic imagination the intense psychological drama of Judas’s betrayal of Christ, and the ambivalent place in Christ’s story of Mary Magdalene.

The religious allegory is strongly signalled, particularly in the final section, with the Foreman suddenly adopting Judas’s trademarks, the kiss and the suicide by hanging. To me it is the least satisfactory aspect of the ballet - a dress, in a sense, that doesn’t persuade me, whereas the psychological split of the human soul resoundingly does. In any case, it might be worth noting that this Christian theme was provided for a ballet whose composer is Jewish and whose original protagonist is Muslim. So whether the Judas/Jesus symbolism is more than a compromise feature on a ballet whose core of self-loathing is the more important material is up to the viewer’s requirement for comfort in the lacerating 40-minute experience of watching The Judas Tree.

There was certainly plenty of ancillary material to pick up on - MacMillan, with an alcoholic, depressive, drug-addicted past, was then under weekly psychiatry, and eagerly exploring his own sense of his divided self, and particularly his interest in the guilty ambivalence of human sexuality. (The balletomane and political commentator Frank Johnson once told me that he thought 80 percent of men had a gay element inside them that they wanted to resist.) I’d suggest that another, less conscious reflection came in from the ballet studio itself: the fact that ballet is by its tradition communal, the fact that women are the precious, strongest ones with the highest skills, the ones the men must always be supporting with utmost physical care. This experience, which runs counter to the outside world (and particularly that of East London streets at night), was one that MacMillan himself would have had dinned into his training as a classical soloist. Why not turn this on its head in this ballet?

Although in 1992 I was horrified by the ingenious literalness of the violation of the sole woman by all these men, now after many viewings I no longer think that: I do not believe the creator of Juliet, of the three tragic sisters of Las Hermanas, of the sassy girls of Elite Syncopations, can have been a misogynist. Plus there was (not to be ignored) his chip on his shoulder about his working-class origins. The Judas girl, the “Magdalene”, is as much posh office totty getting what’s coming to her from the working-class builders whose homes she is razing, as an under-educated council estate girl wantonly inciting local men to prove her desirability to her damaged self. If that idea is shocking, it only proves the electric power of the naked thought in an artform whose lure had been built up in tulle-like layers of disguise, prettiness, elegance, grace, melancholy, fatalism, abstractness.

Irek Mukhamedov, the original Foreman of this complex ballet, has been back in London from his Greek base (where he is artistic director of the National Opera Ballet of Greece) coaching the new Foremen in this revival, Carlos Acosta and Thiago Soares.

It is the young Brazilian Soares - a man who at the Royal Ballet has rapidly come to embody an almost unparalleled range from drag character parts to princely roles - who I suspect may best relish the extremes and ambiguities of his character. He is one of the most exciting performers to have joined Covent Garden since MacMillan's death in 1992. We met this week at the Royal Opera House, only a week before the 28-year-old Soares must take on this strange ballet and show us why The Judas Tree is not gratuitous nastiness but a shudderingly strong, maybe prophetic piece of theatre that truly resounds of the way people think of themselves.

ISMENE BROWN: This is not your first encounter with The Judas Tree.

ISMENE BROWN: This is not your first encounter with The Judas Tree.

THIAGO SOARES: No, seven or eight years ago when I first came to the Royal Ballet I danced the ballet as one of the pas de trois boys from the corps . At the time I was getting to know all the rep here, the MacMillans, the Ashtons. I had been only a year and a half in the company, and I had a lot of curiosity at the beginning of my career here, I was fascinated by Kenneth’s work. The first ballet of his I was in was in Mayerling, in the corps, and I was going, “I wish I could do more of that.” I was thirsty for it. Then I got involved in Gloria and Judas Tree, and it was very lucky to find that Irek Mukhamedov was to perform it, the original Foreman. I got a taste of the ballet’s propositions.

Were you disgusted? shocked?

No, I felt shocked in a good way - thinking how far this man, Kenneth MacMillan, could go with ballet. How far he pushed the combinations of choreography and the drama, and all the possibilities that it gave the audience - you could see so much. I felt, “Oh, my god, how much you can do with this piece, how much you can do with the body, to get into those positions.” That was my first reaction. And it was telling an obscure story at the same time.

So now that I’ve been given the leading role, I’m really enjoying it, I’m in the moment, and I’m aware that it is very rare that you will do a role when the original cast is there, helping you to get through the journey. Irek, Jonathan Cope who also did the role, and the notator - all working with you. So I am trying to get the best out of all of this! It’s very challenging, very good.

To you this is a dream role... but for the audience, this is no dream! It is a horrid experience. People still think it’s ugly, untrue, misogynist.

Well, yes, there is a point of view. Obviously the new audience’s point of view is here, and there are people like you who have seen it many times, done in many ways. But I don’t think of that. I’ve just been given the role, and I’m working as hard as I can to make this possible on stage, well received, to make it look well-written, to give my best performance. It’s too soon for me to think about what the audience sees, the result - because right now I’m still in the learning process, I’m still taking in information.

What did Irek say about it when he coached you? Did he have to draw something frightening out of himself on stage? Because he was very frightening in the role. And do you feel you must too?

Well, he didn’t use those words. But he has been giving me the idea of what happens in that event that you see. What is supposed to be happening, as originally invented. And he is trying to get the best out of Carlos and me, trying to pass on the role to us.

What instincts do you have to draw out in yourself, in order to portray this man who leads a gang rape, and who kills not only a woman but also his friend, and then himself?

To me this man represents all sorts of men - the kind man, the rough man, the coward, there are all sorts of themes represented there about relationships of man towards woman. Also there is a base under it of Judas-Jesus-Pedro-Magdalena.

That religious part speaks to you?

Yes. I am Evangelical by my family background.

But Irek of course is Muslim! And this is a Christian story. How did he relate to that?

I think because we’ve been working so intensely on the piece, we haven’t actually sat down, for me to hear his questions about the piece. He has been giving me information about the goal of the piece, and we are trying to achieve that.

What is the goal?

To me it is to try to make those events feel real. Something that maybe you have a dream about - or that actually happened. Or even something that teaches you about men.

Sometimes in the ballet the woman is very strong, she grabs you with her leg around your neck, and you are as weak as a little cat, you are nothing

It’s a horrible lesson for women to watch.

Yes. But I sometimes see a woman there on stage who is a player, who takes power over the men. Not just a victim. Sometimes in the ballet that woman is very strong, she takes control, she grabs you with her leg around your neck, and without her hands she puts you on the ground - you are as weak as a little cat, you are nothing. Then suddenly you suffocate her, as if you were an animal. So as you break it down, you see what this hand means or that gesture - not just a push around the back here, but a gesture of protection. Little details that Irek knows and he will tell you. A jump that is a double saut de basque that I’ve been doing for momths, and it ends with an arm out - Irek said to me, “What are you doing with your arm?” I said I’m reaching. He said, “No, you’re pointing. You’re pointing to him, or him.”

You’re trying to manipulate the other guys to see the action your way, through your eyes, getting them to join your team. I remember how Irek did that - the more powerful he seemed, the more vulnerable he seemed, the more of a bully and more likely to be a coward. But maybe you will do it differently.

Well, if you go straight to the point - I’m the head of a gang of men who play with human beings. I bring the girl, as a victim, to play. But I’m the only one who doesn’t get it in the end. Then perhaps the devil takes over your body.

The killing is because he is impotent - he is the only man who hasn’t had her.

It’s funny talking about this, because this afternoon I was doing a solo, jumping as high as I could, and Irek said, “What are you doing there?” I said, “I think I’m reaching as high as I can.” He said, “No, this is kind of like a ritual possession - because you didn’t get her. So this is a kind of possession, where you are almost in spasm.”

Because in the rape all the other guys got rid of it, into her, they pushed away the feminine part of themselves... you are the only one who didn’t get rid of that.

The difference between my first and second solos is that in my first solo you are driving yourself in those steps with these looks and pointing gestures - but in the second it’s not you doing it, it’s like another kind of power has taken over your body. There is a fantastic movement when Irek freezes for a moment, but his body trembles, as if he can’t control something inside him.

It’s like shivering involuntarily - but I wonder if he did that for MacMillan or MacMillan found that for him? Because the great thing about Irek was that he was so great as portraying the inarticulate, powerful man. Judas Tree picks up what he did so fantastically in Spartacus - the man who can only express everything in his body. But in a way you must have completely different instincts from him?

I have a huge respect for Irek. When I go back to my childhood I grew up watching Irek videos, the Bolshoi tours, and his famous La Bayadère with the Royal Ballet - I always admired him a lot, so to be lucky enough to have him there driving you to s a sense of the role. He created the role, and so far I have nothing to question about how he did it. I am just trying to catch up with all the information I’m being given, at the moment.

You have to make sense of what MacMillan, Brian Elias and Jock McFadyen made happen! It was a collision of their ideas, a combustion. But in that ballet, the first critics’ reactions were shock and disgust, but those who had three days to think about it, the Sunday critics, found it much more symbolical of a man struggling with his masculine and feminine sides. With Irek that worked very well, because he played it very butchly. But you are a more subtle character, with a more sinuous body. I think Irek would have a hammer on him, you would have a knife! I mean, how far when you take a piece of choreography do you want to go into the choreographer’s head? Because it is a very dark place.

Well, perhaps there are thoughts you don’t want to share, or you should not share, which will be the secret of your unique view. But there are definitely thoughts there, there is definitely curiosity in me. But when you’ve been given a role, and people who know it very well and danced it are heping you, perhaps you just have to learn their journey first. Learn what happened, and then I believe there is a little bit, when I am getting there, and maybe a few days before my performance I start to touch it with my own thoughts and perhaps my own abilities, which will make this interpretation unique for me. MacMillan was such a rich choreographer that without you changing the choreography he allowed you to do that. That’s why all dancers all around the world want to do Kenneth’s work - because it always allows you to put yourself into it.

How much will happen in actual performance? Do you like to busk spontaneously in the performance or do you prefer to calculate and plan it all as much as possible before?

I have a tendency to rehearse a lot, but I always leave room for thoughts that will come suddenly. Maybe the people taking your rehearsal just tell you to look in a slightly different direction and it gives you an idea, or a last-minute adjustment. But you do allow for what happens on stage - if you drop something on the seventh beat instead of the eighth beat, it is natural to change the way you notice it, see it quicker, give it a slant.

But this is also a piece of such complex music, it is highly specific, so I am trying to work as hard as I can to really get to know the music, get to know the space of the stage that I have to cover, get to know the dancers I’m with, and the timing of other people. It’s also the relationship with the other men in the cast. And figuring out the relationship between my role and the figure of the Magdalene is... complex. It’s like normal relationships - who drives when, when you let it go, when you drive something. In pas de deux there is a lot of “putting” her in the right place. But this is an exchange - when I punch you, when you punch me, when I pinch you, when you pinch me - it’s like an exchange of rough words in steps. Perhaps it’s a rude exchange.

The sexual imbalance in ballet is unique. Out in the world women are invisible, but here on this masculine place, a building site, the woman walks on like a spark into a tinder-box

You get a little of that in William Forsythe. But the other thing is that though people see it as men’s power over women, or women inflaming men - actually I think there is another layer which comes from what ballet is itself - because it is ALWAYS the woman people look at! All these guys are doing all this big butch stuff, but the moment the girl walks on, we all look at her. The sexual imbalance in ballet is unique. Out in the world women are invisible, but here on this masculine place, a building site, with all these powerful men - and we know what men are capable of in a gang - the woman walks on like a spark into a tinder-box. She can cause trouble! So it’s intensely fascinating.

Yes, she certainly is. But what did you think when you first saw it?

First time I was shocked to my withers. It was the breaking of the porcelain ballerina. But I had been so captivated by Mayerling, Las Hermanas, The Invitation, Juliet, even Manon, that I knew MacMillan was not misogynist - he had a deep understanding of women. But where it falls down for me is when after the gang rape he gets the gang to kill the friend, I don’t understand his power there. Because it’s a trigger point. For me the ballet breaks there, when the religious element takes over the narrative.

That is where I’ve got up to so far. To me, I think it’s checkmate. That’s where the coward, the figure of Judas, is at his lowest. You now know exactly what his figure represents - because up to that point he was the boss, he ordered them about, he slapped them, made them follow him. Right there the picture changes into a little baby who is scared of everyone, and his only way is to blame someone else.

But why do they obey him? He didn’t get any sex - he is impotent! He’s been shrunk! So how does he have that authority over them?

Perhaps he crossed the line of the gang. Perhaps he for real killed her.

And then the hanging - which looks so careful, because Irek nearly hanged himself first time...

He told me this, and it is really scary doing it, actually. The technicians do it beautifully, they really take care of you, but it’s a funny feeling doing it - I did it for the first time on Sunday. It’s strange, because it’s for real. You have a collar, and the cable is attached to your suit - but you have little time, just six counts to check the belt and then throw yourself off. Carlos and I tried on Sunday a couple of times, and we were, like, yeah, quite a sensation! It’s quite a sensation! Because it’s real, and it’s quite a long way to drop. They have a guy behind us who nobody can see. Nothing will happen to you!

But in your imagination it might... Sorry!

No! I think it closes the ballet very well. You see, I haven’t watched it from the front much. I’ve seen videos and documentaries about it. I only saw one show all those years ago from the front. I like to watch a lot of performances, and even here with our colleagues we come to see second cast, third cast, and you’re right, lots of things change from the front.

How important is it that Mara [Galeazzi, Soares’ partner as the mysterious Woman] is experienced in this role? Does she change things much or do you have to ensure everything is exact?

Well, as you say, she’d done it a lot with Irek, so she’s at home in every hold. And she is experienced in the journey too because she did it with a lot of people - so her bag is full! She knows when, and what, and how.

How does she come across to you in it? Her role is very changeable according to the performer. Leanne Benjamin is very ballsy and resilient, such a street-kid - Viviana Durante [the original Woman] was more flirtatious, Gillian Revie was extraordinary in a very feminine, bathing-beauty kind of way, passively enticing. Mara has an elegance about her... does she portray something for you that is more Madonna or more whore or lover or mother? Is it too early to say?

I’m with you. The thing I find interesting is that perhaps I see many women in Mara, because she is not a single individual. She can be a very sweet person, then very sexy and manipulative, a snake, or an accuser. Perhaps evil. And makes you do something you don’t want to. She’s been here a long time and is very experienced in character-playing. I think you need to know that journey well, because it can be rough - what we do with those girls, with Leanne and Mara. To put up with the energy of a gang of men pushing you, bullying you, and then when they start the rape, it’s disturbing. I mean it’s in a beautiful way, as theatre, when you see the whole picture - but it’s all sorts of men lurching at you aggressively in your face. It takes a lot of will to stand up for that.

And what about you men doing it? Because you are not used to behaving like this either! You are used to being supportive of your women!

Well, so far I’ve been having private calls, in the learning process, so I haven’t yet had the bigger picture.

I think for a woman doing the show, if your performance is to convey both the intense fear any victim would feel and also the resilience to survive it, and for the event’s sheer scary and ambiguous horror is to come across, you would need an extraordinary openness in performance of the last percent to make us in the audiences sweat with fear, understand the emotions - and not just say, it’s a gratuitous portrayal of a repellent event that is very well rehearsed.

To be able to make it happen. Yes.

I wanted to ask you about Brazil - the film Only When I Dance, when I interviewed the producer and the extraordinary young ballet-dancer Irlan da Silva - and he had the same teacher as you, Mariza Estrella!

Mariza!

Irlan told me that it was true that his upbringing was full of fear, that he did have a desperate urge to escape from the streets of his favela. I don’t know if you had a similar background, and knew the same kinds of dangers, crime and street life - and whether, if you had, that had any relevance to Judas Tree, psychologically.

You mean, if there is elements of my “rough background” there?

I don’t know if you had a “rough background” or a middle-class one.

Irlan’s reality was a very extreme reality. The film was very beautiful, but there are aspects of his life that are atrocious - people fought with guns, and as he went down to ballet school he was dodging that. But as you say, I came from more middle-class, lower-middle-class family, and I grew up in the street and played football and went to circus school, and I had a lot of friends with less possibilities and less hope, and also friends with more possibilities and more hopes.

But yes, there is an aspect of that. You hang around the streets, and you learn sneaky things to survive. It was not as extreme as Irlan’s, because he was actually in the favelas. I grew in a place where the biggest favela was at the top of my street, so you met a lot of people. As soon as I started to become a young man my mum said, “Go, go into the streets, grow up and find your way.” And we had a lot of experience of clubs where you shouldn’t go, exchanging things for money that you didn’t have... those sorts of things stay with you, not as rough as favela life, but still surviving on the street.

I’m thinking that Judas Tree appears to be about boys’ gang behaviour - but MacMillan was a solitary boy, not a gang member. So on the one hand it may be useful to know about gang behaviour - if it’s a portrayal of gang mentality - or maybe actually this is a portrayal of a solitary man’s idea of war inside his head.

Actually that’s very interesting - you’ve given me ideas. In South America we do have such a reputation, and we do have such huge links with gang behaviour, and a lot of favelas. That does relate to people and how they live and behave. You exchange information about experience, and you also learn to adopt their roles, a little. There’s a lot of that on the street - you know what could happen. There is a lot of warnings, and I-told-you. That is something I definitely have memories of back home.

Fear.

Yes. I mean - don’t mess with those sorts of people, or with that man. Or you learn how to behave to make people not to mess with you.

You started off in circus school - what were you good at?

Back flips, tumbling. I had a lot of ability also for the acting scenes - in Brazilian circus we had scenes that linked from one act to the other, so I always had a lot of theatrical skills. I could speak, I could be funny out of context, or make something work theatrically. And because I came from street dance as well I had rhythm.

Don’t you miss that now? Ballet must seem so un-spontaneous.

No. There is a lot of aspects in ballet, even in pure classical ballet, that you can play with. If you catch up well with the training and what it should be, you can play with rhythm and speed, quite a lot. Perhaps someone looking at say hip hop tricks here, or ballet entrechats six there, might get some idea, but if you come to do the training for entrechats six, you’ll see there’s a lot you can do with speed, height, timing. There are a lot of aspects, so you can’t be bored with it.

Ballet is a very interesting thing to do!

Yes.

You were born when?

In 1981. Nela [Marianela Nuñez, Royal Ballet principal and Soares’ fiancée] and I are just about to meet up in age, because on the 23rd she is about to be 28 as well, then I’ll be 29 in May. I like that! We meet! We go, yeah!

In Brazil you knew Roberta Marquez [Royal Ballet principal].

Yes, we danced together when I joined the Teatro Municipal. It all started off when I was in Centro de Dança in Rio, and they immediately thought I was something special. I didn’t really know what they were talking about, but it was the length of my neck or the length of my arms or something. Mariza after my first year wanted me to have special teachers - she tried to stop the world for me, found Russian teachers, Cuban teachers. She was trying to find every way she could to push me on.

But when I first went to ballet studios I wasn’t very excited about circus any more, because my circus teachers said I could do theatre, other things, they were making me feel out of place, I was getting too tall, too long - I was 11, nearly 12. My flicks took too long, and I was feeling out of place. I was very interested in hip hop because my older brother was into that, and they got the girls and they got the attention. Everybody knew them in the streets. They went to competitions as well. And everybody had a job.

They said, 'Take your trousers down.' I was quite surprised but they wanted to look at my legs, make sure I didn’t have crooked knees

So I started doing that, and when I got to 14, 15, the choreographer of this group - who used to be a real jazz-ballet dancer - told me, “You could be a great dancer, you’re fast, you’re clean, you’re this, you’re that. What about jazz dance? Or classical? It may help with your street dance.” I thought, well, maybe, I don’t know. He sent me to see Mariza. She was thirsty for a real guy, because she needed boys. There were a few, but they were studying for other reasons - not because they wanted to be dancers. And I arrived, and I was quite strong, and could lift the girls. And my jazz teacher straightaway took me aside with Mariza, and they said, “Take your trousers down.” I was quite surprised but they wanted to look at my legs, make sure I didn’t have crooked knees, and see if this training would be a waste of time at 14. Because if they couldn’t take someone on to be a principal it’s a big investment to waste. So that’s how I started.

After my first year and a half, I was getting quite good quite fast. They needed to keep polishing me, cleaning me, because I had not done it since I was five. Mariza introduced me to a lady who knew people all around the world, and privately I was studying with two special teachers, Russian and Cuban, and started going to competitions. Mariza paid for everything, paid for all my studies. So whenever she called me to dance in a supermarket, I would go! And they sent me representing Brazil to competitions - so I got our first silver medal and it began there. I came back and suddenly realised it was possible to be a ballet dancer. Then they invited me into the company to do main roles, so I started doing Swan Lake straightaway and there I met Roberta - because she was coming up - and we did all the classical rep together.

You both have a connection with Natalia Makarova, don’t you?

We both met her first time in Brazil, because she put on three productions in Brazil, Swan Lake, La Bayadère and Paquita. Natasha was always in love with Roberta, because there were aspects of Roberta that reminded her of herself. My first big role was Solor in Natasha’s Bayadère, and she was wonderful, really happy for me to do it, and after that I went to the Moscow Competition with Roberta, representing Brazil.

Yuri Grigorovich chaired the judges?

Yes! It was when my career started to look as if it was going well. I got a gold medal and Roberta got silver. So we came home and had a big party Then I had an offer to go to the Kirov under Makhar Vaziev - he knew my teacher in Brazil. He gave me a contract, and I was thirsty for more, to have new experiences. I knew nothing, and I wanted to learn, so I went - like that! It was fantastic - I learned a lot of pas de deux there, because whenever Makhar needed a guy for a call, he’d order me to go and do pas de deux with Yulia Makhalina or someone in the studio. Makhalina was very sweet indeed. Then I was invited to join the third Moscow company, under the director Gordeev who wanted a tall guy who knew Swan Lake. So I did his Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty, Don Quixote - that’s how I learned the rep! I was even dancing in Ufa! I had to learn a little bit of Russian.

There is only one place that I think it is worth your giving blood to get into, and that is the Royal Ballet, because of their repertoire

Then I was invited back to Brazil to do Vasiliev’s Romeo and Juliet, his new production, with Roberta. Then my teacher said, all this is great, Thiago, but you need to be in a place where you will be given more vision, will see different things. There is only one place that I think it is worth your giving blood to get into, and that is the Royal Ballet, because of their repertoire.

You must have a tiny blood relationship with Margot Fonteyn, because of her Brazilian family.

We are both born on 18 May! Obviously I had Royal Ballet videos, and they knew Jeanetta [Lawrence, assistant director of the Royal Ballet], so they got me the opportunity to audition. Ross [Stretton, then Royal Ballet artistic director] had seen me in the Moscow competition, and I knew there was a green light for me to come and audition. They made arrangements, I came to London to audition, end of 2001, and in fact Monica [Mason, now artistic director] took my audition. She said, “We understand you have all your medals and so on, but here there is a whole new tradition for you to learn, so you should take a lower contract as First Artist, and progress.” I didn’t think twice, I just thought this is definitely the right place. I had to wait until 2002 to join.

You never regretted it.

No, no. The moment I stepped in here I saw certain ballets that struck me. The plus artistically is everything, it is worth it. It’s hard, but these are the ballets I wanted to do. So in Mayerling I was only in the corps, in the wings, watching, but I knew that one day I wanted to do that role of Rudolf. You also have to remember there are a lot of talented people here, and you don’t know how it will shape up. But I was happy that step by step I progressed up the ranks. And also I feel very lucky to have such a generation of colleagues - Tamara [Rojo, Royal Ballet principal] was the first person to put a thumbs-up for me, and I will never forget that. There was the opportunity for me to step into being a Prince for her, and she liked me. You never know, it might not have worked. There was good momentum.

To work with exciting colleagues must be the best thing you can ever want. There are talented dancers who have unsympathetic colleagues or company, and their best years have not been spent as happily as could be expected. But which are you? The Prince? Or an Ugly Sister? No one has had such a range as you from character drag parts to prince roles - perhaps since Robert Helpmann.

Well, I’ve been given roles that sometimes don’t have tradition of character dancers, but I try not to think too much about it just to achieve the best I can with that particular role. Obviously I am a principal dancer now, so my roles are often much-repeated ones as a prince type - but I was very lucky indeed to have the opportunity to do such a range of roles before. It gave me the chance to see different angles on ballet, and you learn how strong theatre can be. And how the little things can make such a difference. Obviously you aim for certain roles - Rudolf in Mayerling was always my goal. But I try never to have my mind closed to any role.

You look so naturally theatrical in all sorts of roles that sometimes are neglected - you bring them brilliant style and very strong character. When you do a leading role you seem to be as much focused on character role as on the academic classical purity.

No one can do everything. Obviously someone can do a great range, like Anthony Dowell who is now doing GM [the older man in Manon] and character parts, but there are tracks you are on at certain times, and as the career grows and age comes, perhaps you won’t have the same strength and speed, and you can achieve other goals with other roles. Especially here at the Royal Ballet, the character roles are seen as something as high and important as the prince. In other places there is not the same respect. I mean a role like Tybalt in Romeo and Juliet - you don’t do one step with your leg, but the dramatic range you have is amazing. All the guys want to do that role.

You can completely dominate the stage, wipe the stage with Romeo. Stephen Jefferies was another, like you, who could totally dominate the stage.

For me I’m almost 29 so I’m getting into my physical prime at perhaps 32, when I’ll have experience in the bag as well - so I’d like to extend my goals in dance as far as I can, so that I know I could later on extend my career in other roles.

What about the more abstract physical ballets? I don’t see you so much in Balanchine, Forsythe, McGregor.

I love McGregor, I love the guy, I’m very interested in his work, but I never have been chosen to do it yet. I did quite a lot of contemporary ballet in the past, but it’s down to... like Wayne, for example, if he chose me it would be a pleasure, but you have to respect his choice.

There are Balanchine parts that really want character in them, the roles of Jacques d’Amboise, Edward Villella - Apollo, the Agon pas de deux man.

I would love to do those. I have always really wanted to do Prodigal Son, the story because of our religious beliefs, my father used to read it to us when we were little - plus it is such a great ballet. It is one of those where it’s storytelling as well as extraordinary steps.

What are you doing next season?

I don’t know yet - we don’t know casts.

What would you like to?

Cranko’s Onegin, obviously, as I did it before - but you don’t know if you’ll get cast again. I feel very comfortable in that ballet and that role. And there are more MacMillan ballets I would like to be involved in, like Winter Dreams, beautiful music. And we’ll be doing Cinderella for the first time, with Marianela.

Prince now - no more Ugly Sisters!

No more Ugly Sisters! And Albrecht I would like to do again.

Are you planning to marry Marianela or stay engaged?

No, we’re definitely getting married. I want to, I want to. The problem is we are so busy, and I’ll get called away or Marianela will, for guesting. But we will definitely do it very soon. People keep wanting to hear when it will be! Because we have been engaged a while. But you do also want to make it more about “us”, and not such a performance. You want to tell people that you love someone, but not to make it into such a public “event”.

Add comment