As its first gift to dance fans, the new year has delivered not one but two chamber pieces about extraordinary women. Down in Covent Garden this week, Will Tuckett's Elizabeth for Royal Ballet dancers is exploring the life and loves of Queen Elizabeth I, while up in Camden Akram Khan's Until the Lions takes a fresh look at the story of princess Amba, from the Indian classical epic the Mahabharata.

Amba's story is seen through the lens of poet Karthika Naïr, whose new book Until the Lions: Echoes from the Mahabharata explores the voices and viewpoints of the epic's hitherto silent female characters. Princess Amba is abducted by a warrior, Bheeshma, but released when he discovers that she has a true love, Shalva. But Shalva rejects Amba because she now belongs to another man, and Bheeshma refuses to right the situation by marrying her, since he has taken a vow of celibacy. Amba swears to revenge herself on him, and after years of penance, Lord Shiva prompts her to self-immolation so that in her next life she is reborn as Shikhandi, a woman-turned-man who trains as a warrior and kills Bheeshma – who recognises and accepts his doom – in battle.

Khan was famously in Peter Brook's stage version of the Mahabharata as a teenager, and has returned to it in his choreography before, with the haunting, fiery Gnosis in 2009. Until the Lions follows that work quite directly in some ways: it has the same flexibility of gender assignation and the same centrality of strong female characters. Like Gnosis, Khan opts to tell a traditionally Indian story through the medium of his contemporary, rather than his classical Kathak dance background; though there are Kathak shapes in there, Until the Lions is defined by a spiky, otherworldly feel that slightly recalls his recent technê for Sylvie Guillem. Khan's trademark penchant for sharing the stage with strong female collaborators is more in evidence than ever: the other two dancers in Until the Lions, birdlike Ching-Ying Chien and muscular Christine Joy Ritter (the latter pictured above right, with Khan), are both utterly magnetic performers, frequently detracting attention from Khan, who gently choreographs himself into the background – partly because the story demands it, partly also, one suspects, to give his 41-year-old bones an easier start to a busy year

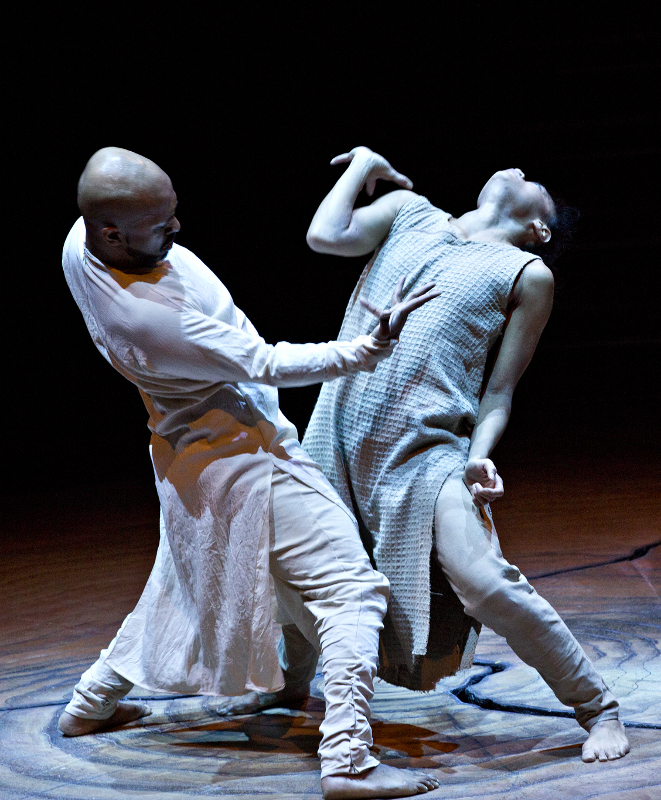

Khan was famously in Peter Brook's stage version of the Mahabharata as a teenager, and has returned to it in his choreography before, with the haunting, fiery Gnosis in 2009. Until the Lions follows that work quite directly in some ways: it has the same flexibility of gender assignation and the same centrality of strong female characters. Like Gnosis, Khan opts to tell a traditionally Indian story through the medium of his contemporary, rather than his classical Kathak dance background; though there are Kathak shapes in there, Until the Lions is defined by a spiky, otherworldly feel that slightly recalls his recent technê for Sylvie Guillem. Khan's trademark penchant for sharing the stage with strong female collaborators is more in evidence than ever: the other two dancers in Until the Lions, birdlike Ching-Ying Chien and muscular Christine Joy Ritter (the latter pictured above right, with Khan), are both utterly magnetic performers, frequently detracting attention from Khan, who gently choreographs himself into the background – partly because the story demands it, partly also, one suspects, to give his 41-year-old bones an easier start to a busy year

Khan, Naïr, and dramaturg Ruth Little have gone for an impressionistic, rather than an exact retelling of the story; certain moments are clearly identifiable, but at other times it's hard to tell where we are in time, who is playing whom, or what they are supposed to be doing. I will admit to wavering attention during those parts of the piece, but it's never less than a pleasure to soak in the atmosphere created by Khan and collaborators, particularly the set, a stunning use of the Roundhouse space by visual designer Tim Yip and lighting designer Michael Hulls. A round stage decorated to look like a tree stump, with rings and bark, is crossed by crevices, like cracks in stone or in the earth's crust. The floor can shift under the dancers' feet along these crevices; smoke rises and lights shine out of them like subterranean fire; thin bamboo poles are planted in them to look like arrows lodged in flesh, or bare reedy trees.

I have never seen a human gallop so fluently on all foursThere are some truly wonderful moments of dancing. A duet between Chien and Khan showing Amba's attempt to persuade Bheeshma to marry her, is tense and erotic in a way I don't recall seeing in Khan's choreography before; Chien reaches for Khan to touch him, to hold him, and he alternates between reciprocating and pushing her off, though he seems to succumb in the end (this week in January will always be remembered as the week in which we saw both Carlos Acosta and Akram Khan, two of dance's most chivalrous, gentlemanly stars, simulating sex on stage). Chien fascinates with her kinetic contortions during Amba's period of solitary penance, and Ritter – who plays various roles including Shikhandi, the male persona in which Amba kills Bheeshma – is strongly disconcerting in her creaturely movements: I have never seen a human gallop so fluently on all fours. The final confrontation in which the two other dancers align to "kill" Khan, is a very clever piece of stagecraft for the round stage and round theatre, the three of them rotating in a line so it feels almost as if we, the audience, are spinning about them like a film camera on a 360° tracking shot.

Filling in the space between dancers and audience are musicians who, like a chorus, inhabit the perimeter of the performance space and join in the action from time to time. Their use of the stage itself as percussion instrument is eerily threatening, recalling the drums in Stravinsky's Rite of Spring, and there are lyrical passages of haunting melancholy, like Gaelic love songs, mostly courtesy of guitarist Vincenzo Lamagna, and vocalists Sohini Alam and David Azurza – the latter contributing to the piece's gender fluidity with his remarkable countertenor.

The occasional confusions and longueurs notwithstanding, Until the Lions a beautifully designed, carefully considered approach to a strange but compelling story, and the strong central performances lift it past its problems of structure. It may not be in the league of Khan's very best work, but it's firmly in the stable of the good.

- Until the Lions at the Roundhouse until 24 January

Add comment