The credits unfold against a backdrop of a tall, exotic plant, down whose length the camera slowly pans. The African Queen, in glorious Technicolor, based on a novel by CS Forrester, directed by John Huston, shot by Jack Cardiff, starring two of the great names of the cinematic age. Katharine Hepburn, the female face of the screwball comedy, and Humphrey Bogart, the hardbitten star of Casablanca and The Maltese Falcon. If you’re reading carefully, you’ll note that the credit for continuity goes to Angela Allen. Sixty years later, I sit in a cinema in Soho with Angela Allen and watch The African Queen.

Angela Allen (b 1929) was only 22 when she was hired to fly out to central Africa, having already worked in continuity on the second unit of The Third Man. She went on to make 13 further films with Huston including The Misfits and The Man Who Would Be King, and also worked more than once with John Frankenheimer, Sidney Lumet and Franco Zeffirelli. But it was The African Queen that she first sat on set next to a major Hollywood director.

The film is in effect a two-hander, but on an epic scale. Bogart plays Charlie Allnut, a boatman on the Congo River who delivers mail to an outpost where Miss Rose Sayer (Hepburn) helps her missionary brother (Robert Morley) bring the Good News to the natives. Mr Allnut (as she primly calls him) brings bad news of war in Europe, and soon imperial German troops arrive to burn down the village, the padre collapses and dies and Rose is forced to flee in the African Queen, the old bucket of a steamer whose pistons need coaxing back into life with the odd brutal kick from the skipper's heel.

The dauntless Rose conceives a plan to attack the armed German boat patrolling the lake many miles downriver by persuading the resourceful Charlie (as she comes to call him) to customise up the bits and pieces of equipment on board. Along the way they have to get past huge crocodiles, foaming rapids (shot with dummies in for the actors), a German fortress and a swampy maze of leech-infested waters. The pair of them are of course chalk and cheese. Rose is a God-fearing teetotaller, while Allnut fuels up on gin. Naturally, as obstacles are tackled and they draw closer to their prey, they tumble into each other’s arms.

The African Queen has been ravishingly restored at a cost of $650,000 by ITV Studios Global Entertainment, Paramount Pictures and Romulus Films. In its new incarnation every bead of sweat on Ms Hepburn’s freckled face comes up a treat, every lump of stubble on Bogart’s grizzled chin is pin-sharp. And it’s as if the greens of the Congo River and Uganda, where the film was shot, have been given a fresh lick of paint. The result is available for inspection at the BFI Southbank in London, the Filmhouse in Edinburgh and other cinemas.

The African Queen has been ravishingly restored at a cost of $650,000 by ITV Studios Global Entertainment, Paramount Pictures and Romulus Films. In its new incarnation every bead of sweat on Ms Hepburn’s freckled face comes up a treat, every lump of stubble on Bogart’s grizzled chin is pin-sharp. And it’s as if the greens of the Congo River and Uganda, where the film was shot, have been given a fresh lick of paint. The result is available for inspection at the BFI Southbank in London, the Filmhouse in Edinburgh and other cinemas.

Bogart won the Oscar for his performance. Allen had to wait for her awards. But after a lifetime of service to the film industry the recognition started to pile up: an MBE, an award from the BFI and, in 2005, the Michael Balcon Award from Bafta which she accepted from Anjelica Huston. Of all the arcane job titles given to people who go about their work on a film set – key grip, best boy, gaffer etc - the role once known as continuity girl carries huge responsibility. Featuring alongside a gallery of images celebrating her life in film, in this wide-ranging conversation with theartsdesk, a surviving link with the golden age of Hollywood recalls her ride on The African Queen and other journeys.

Watch the trailer for the newly restored The African Queen

JASPER REES: What is (or was) a continuity girl?

ANGELA ALLEN: The role when I started was called continuity. It didn’t have "girl" because it was just women who were doing it. They changed much later to the title “script supervisor”. Identical job. Nothing changed. You have to observe everything that goes on on the set on every shot. You are there sitting beside the director – hopefully - and you are responsible for seeing that the actors say the correct lines, rise on the right words after you’d done a master shot, make sure they’re wearing the right clothes the right way, the props are in the same position. You listen if the director makes any comments and you take them down. You don't dictate anything. You’re responsible for telling him if you think he needs any extra shots. And correcting him if the eyelines are incorrect. You have to step in and say, “It has to be over the right shoulder. He was on the right, she was on the left in the master therefore the close-ups have got to be this or that.” It’s a job where you can’t really leave the set. If you want to go to the bathroom you’ve got to put your hand up like at school and say, “Please can I be excused for two minutes?”

Without you, in short, any film could end up being a dog’s dinner?

It certainly could have been or would have been when I started off. After all, we didn’t have video then or even the Polaroid camera. Everybody has to know what takes the director wants to print therefore you have to tell the camera boy and the sound people, and the editor’s checked your notes to make sure they’ve received all the right prints.

You’re a sort of on-set computer.

Sort of. A memory bank.

And how did you become one?

I knew I wanted to work in the film business and I thought I would like to do make-up and then I discovered in those days you had to be able to sketch, which I’ve never been able to do. And then I heard about continuity because I could do shorthand and typing, and was taken to a film studio and just shown around it one day.

How old would you have been?

Eighteen. I’d been working for an artists’ agent. I had known actors because they came into the office all the time. And I thought, this is a better laugh: I’m not secretarial, I think I’m too independent, I don't want to take orders all the time. And I’d heard about continuity. So when I left the agency I literally went knocking on doors. I got myself out to what was then Worton Hall studios in Isleworth and they said, “Yes, we’ll take on an assistant as a trainee. And I got I think the princely sum of 13s and 6d a week.

How long did you have to learn the ropes?

I did three films as an assistant and then they said, “You can go out on your own.” My very first picture was Old Mother Reilly and I thought after day one, that’s it, give up, because they could never do the same thing twice, never say the same thing twice, and I was crying. All the crew said to me, “Don't worry, they’re like this all the time. Nobody can tell them. We’ll help you through it. Don’t get upset.” So I survived that. And then I went on the second unit of The Third Man. I was on the sewer unit in the day, and the main unit was doing all the night stuff. But Carol Reed would come over if an actor was involved with us and then when we came back to London I used to take notes as he viewed the rushes which was incredibly helpful because I’d then see it cut together the next night or two nights later and see how you can change things, how you can improve a scene by putting the emphasis on different people. And Carol had an incredible memory. Smoke at the end of a scene when somebody had said “cut” - he’d remember that. And he was incredible too as a technician and as a director. Even the films I did as an assistant, definitely Carol was the best that I learnt everything from.

Pictured left: Angela Allen with colleagues in her first ever film, Nightbeat (1947)

Pictured left: Angela Allen with colleagues in her first ever film, Nightbeat (1947)

Could you tell you were working on a masterpiece?

No, I don’t think anybody who works on a film ever knows it. You don’t. Everybody always hopes the film is going to be good or be liked but you have no idea how good it’s going to be. Obviously certain scenes strike when you’re watching them as being fascinating but no, I don’t think any of us knew, including Carol.

Of course on set you wouldn’t have heard the music. That came later.

Yes. It was Guy Hamilton who then was the assistant director and the protégé who went to one of the bars and there was a zither player there. It was Guy who brought him over and he played the music for Carol. They [the studio] didn’t want him. They were absolutely petrified. “How can you use this, not a score?” But Carol insisted. How right he was.

If you were on the second unit, how close did you get to those incredibly well-known actors?

The very first shot that Orson [Welles] did, which was walking past a hurdy gurdy in the Prater, was done by the second unit, so Carol came over. And he was a very elusive figure at that time. Everybody was chasing around Europe to get him to come. He didn’t really talk to the crew or people very much. He was there really very briefly. The first unit Guy had to double him in the shadows because he hadn’t arrived. And in the long shots of him running he hadn’t arrived and they had to shoot it.

The first unit came over [to the sewer] to do their stuff and Orson Welles saw the crew eating their bacon sandwiches down there and was absolutely horrified. All the other actors - Trevor [Howard] and Bernie [Bernard Lee] and that lot - were down there having theirs and Orson came down and did one shot and was so horrified that he refused to go down. Actually it wasn’t dirty and it wasn’t smelly at all. And that’s why we had to build the sewers back in London. But it’s so beautifully matched, the building and the way it’s shot and lit, that you wouldn’t know which is the studio shot and which is the real bit.

Were you there when his face is famously seen for the first time?

The doorway shot? Yes. I was there but my unit wasn’t shooting that. And I think it’s one of the most classic shots ever, isn’t it? Incredibly well lit.

How about the climactic scene in the churchyard with Alida Valli? Were you there for that?

We did that. The first time she did it Carol said, “Put her further back.” Take two. Take three. “Put her even further back so she’s got further to walk.” Very brave to have done that shot in one and just held it.

"Put her further back": Alida Valli walks straight past Joseph Cotten in The Third Man

What did that film do for you?

Because I was working and it was a Korda film and you were in those studios, the next big one I got was Pandora and the Flying Dutchman. I was the youngest in the business and I guess because I was in the studio and the production manager put me forward, I think I had to be interviewed by Al Lewin, who was five foot three and stone deaf. I became friends with Ava [Gardner] on that. I even had to double her once. She had to go and swim out to the yacht and find James Mason and that evening she didn’t particularly want to. I was the only youngish female around so I was told to get in the water and swim around for a couple of long shots. Then she’s in all the close-ups.

Did you double for anyone else in your time?

Much more dangerous was when I then went on to The African Queen. It was as if we were going to be shot at by the Germans on the hill [in the film the German soldiers manning the fortress can’t see Rose and Charlie as they crouch down to make themselves a smaller target]. We had done all the work with the artists, they had gone, Huston had gone back and I was left with the second unit to pick up some shots that I knew we needed of the animals [on the river bank] and things like that. Again there were very few females and I was the only one left and I was told, “You’re doubling and steering this boat.” The captain came with me for a dummy run and said, “You can’t go more than a few feet left or right because you’ll go aground.” There were these enormous crocodiles lying on the bank – it was their territory – and I had one little dummy run. I was sitting, because Rose is cowering at the tiller, so you’re not even able to look over the edge to see whether you’re going left or right. And we got right up. These crocs really were enormous lying there with their mouths open. I was 22 when I did that. You’ll do anything stupid. I never got a penny extra for being the second unit director getting these shots and doubling. And my salary – I found an old slip in a desk – was £9 a week.

How did you meet Huston?

I was selected by [the producer] Sam Spiegel in London. I think Guy Hamilton had recommended me and Sam chose me because I think he thought I was the youngest and would be the fittest to survive in the jungle. And Huston was already in Africa so he got me sight unseen.

How easy was it to do your job on that film?

We used to go out on a raft. Down the river we had the prep boat. We also had a half boat that we could put on the raft. Jack [Cardiff] was only allowed two lamps. And he had a generator. The Congo was quite narrow. One day after we did a take Katie [Hepburn] said, “But you weren’t watching, John.” Which is true, he wasn’t. “But I was listening.” Which is true, he was. "But that’s not the same." This went on and she demanded to do it again. We had to turn this whole thing around and once we were about to do it we struck a tree, it took the boiler off [the African Queen] and half the boat to pieces, so by the time we’d turned round and the poor art department had to come in and tried to make the boat it was absolutely hours to do another take. He used the original one anyway, though she never knew.

Was she demanding?

He wanted to pick up another close-up of something we’d done and I said she had to change her blouse or hat or something and she said no and I said yes and she said no and to John’s credit he said, “Well, that’s Angie’s job so we’ll go with what Angie says. Go change your blouse.” I was only 22 and she was this big star. It was quite intimidating for me to say you’re wrong and I’m right. And we didn’t have Polaroids or stills. It’s what I’ve written down. I was right but I never knew that till I got back to London. There were no telephones. It was primitive, it really was.

What was Bogart like?

He was incredibly professional. He was always on time. I think he had Betty [the real first name of Bogart’s wife Lauren Bacall] there with him all the time. There was no entourage. The cabins we lived on on the river boat were pretty small. There was no luxury. They had the same as everybody else. She didn’t have anybody with her. She came by herself. It’s a very different world. (Pictured below from the left: Angela Allen, Katharine Hepburn, hairdresser Eileen Bates, Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall.)

Watching it again, does it bring back sentimental memories?

I have fond memories and you think, we were there then and that was that bit of the river. I can visualise the boat we lived on and what we did in the evening. It’s interesting. Is it because as you get older they say you remember things much more clearly than what you did yesterday? I remember that film much clearer than some. I look down my credits and think, what was that about?

How did that film manage to get made when you consider what the stars had to put up with?

John Huston’s charm, I would think. He talked to them and got them to do it. I think Spiegel got Katharine Hepburn. Bogey would have done it for John and probably had a few rows. In the leech scene [in which Bogart, after pulling the boat through a swamp, emerges covered in leeches] John said, “You’ve got to have leeches and we’ve got a leech trainer,” and Bogey said, “I’m not going to have leeches!” It would have been John teasing him. We had toy ones.

How did you get on with Huston?

Very well. I went on to Moulin Rouge, and then Beat the Devil, again with Bogart. So I carried on with him. I guess we got on because I did 13 more with him. He was very easy. You see, I knew his style. It was simple. He didn't do all this coverage. He knew what he wanted. He never would do a wide long shot and make them play a three-minute dialogue scene. He’d say, “I’m not going to use it. One line, two lines, cut it.” I worked with Robert Aldrich on The Dirty Dozen. That man covered it 360 degrees. I’ll never forget one scene of putting a grenade in a hole. We went round it 360 degrees. Every shot was static, three sizes of lenses - for one word! It was unbelievable. That was an old-fashioned technique. You were told to do the master shot wide, then get in slightly closer, then slightly closer, then cover it all with close-ups or over-shoulders etc. Huston would never do that. He designed his shots, he knew what he wanted. I’d have to say to him sometimes, “I think we need a close-up,” and he agreed.

He took me everywhere. When we did The Misfits it was a very strong union and they didn’t want me because I was a foreigner. His agent said, “I’ll put her in your contract.” I had to have a double, a script boy who did nothing and probably got more money than I did. But that’s how it was.

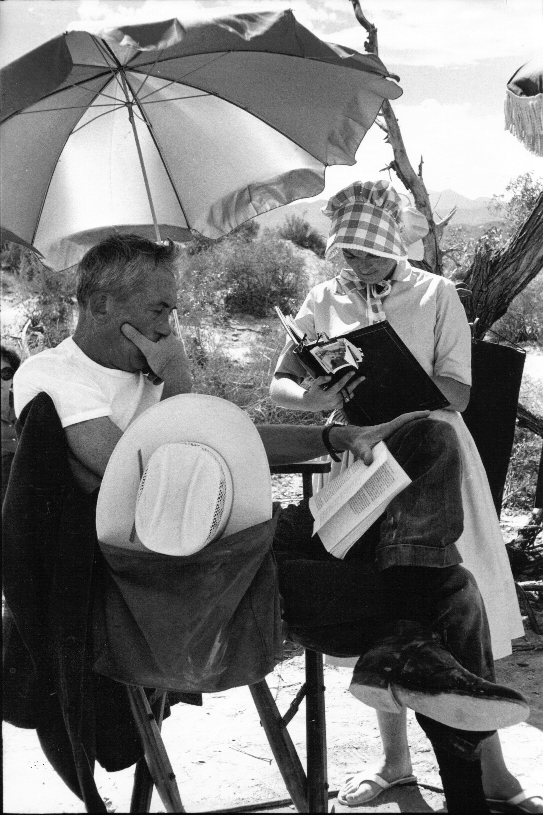

What are your memories of being on The Misfits? (Pictured right: Angela Allen and John Huston on the set of The Misfits in the Nevada desert. Photograph by Eve Arnold.)

What are your memories of being on The Misfits? (Pictured right: Angela Allen and John Huston on the set of The Misfits in the Nevada desert. Photograph by Eve Arnold.)

Well, it was an extremely difficult shoot only because you never knew whether she [Marilyn Monroe] would turn up or not. We had this dreadful woman Paula Strasberg. We used to called her Black Bart. John couldn’t stand her. Arthur [Miller] couldn’t. She was the coach and the manipulator of Marilyn. She was with her all the time. After a take John would say, “Print it," she wouldn’t look at John, she would look to Paula.

Was it a relief to finish the shoot?

It was. The others were all very nice. I got on with Monty [Montgomery Clift]. He got through his scenes on that one in one take. And that was why John chose him to play Freud, the film he made after. Clark [Gable] was the gentleman, the professional. He loved motor cars. I remember spending an afternoon with him when we were off because of Marilyn. We were taken round an enormous warehouse with old cars. Just the two of us going round looking at all these old cars.

He died very soon after the end of the shoot.

Two weeks after the film he was a changing a tyre. His wife was pregnant and he said, “I don’t feel very good.” Nobody called the doctor and he had another heart attack and lasted another week. We’d left and I was in LA. We were very sad. We had no idea. He appeared to be fine and fit and everything on the film.

In recent decades you have worked on several Franco Zeffirelli films, presumably a very different experience from working with Huston.

Franco taught me a tremendous amount about colour, design, costume. He’s a great authority. I’d say he trained my eye. Not that it was a continuity area but I might say, “Did the coat fall in an ugly manner?” and he would say, “Yes, you were right.” I’m a great admirer of his work. The English may find it too flowery but he likes colour. I don’t want to see opera in beige and brown as the English do. I think opera is his first love. And he is very good at it.

You were script supervisor on his Hamlet with Mel Gibson. What was it like for you doing continuity on Shakespeare?

Years ago I had done Macbeth with Polanski. The one thing about Shakespeare is Franco can’t change the words. We’d had terrible arguments about direction and looks but he never seemed to take offence and we’d got on and if he shouted or said something at lunchtime he’d slapped me on the bottom and say, “Are you coming to lunch?” I have enormous affection for him.

"A man must choose whether to forgive or to avenge": watch the US trailer to Franco Zeffirelli's Hamlet

Have you waved goodbye to continuity?

Once you start getting lifetime achievement awards you don’t get the offers.

Would you do a job if someone offered?

Yes, if it wasn’t too physical. It if wasn’t 16 hours standing outside every day in the London streets in the rain, yes I would. I think the brain is still there.

What did winning the Bafta fellowship mean to you, and accepting it in front of a very large crowd and a national TV audience?

That was very nice. I had to make a speech and had very nice jewels to wear and I don’t think I’ll ever get them round my neck again of course. It was a bit intimidating to face an audience when you’re not an actress. I didn't fall up the steps.

Finally, Angela, the job may be called continuity girl or script supervisor, but is it wider than that? Are you also a kind of on-set shrink and diplomat and smoother of brows?

Yes, you have to get on. You may be wonderful at your job but it is personalities. I was lucky enough to find Huston. It was a good working relationship. I’ve never been frightened to open my mouth and make suggestions which all those people appreciated and I found working with a few younger ones who’d come out of film school who don’t want to be told or have anything suggested. They know it all.

- Angela Allen in Conversation at the Fan Museum,12 Crooms Hill, Greenwich SE10 at 7.30 on 11 April. Email admin@fan-museum.org

Find The African Queen: The Restoration Edition on Amazon

Find The African Queen: The Restoration Edition on Amazon

Watch Angela Allen talking about The African Queen at the Cinema Museum

Add comment