The Tales of Hoffmann, English National Opera | reviews, news & interviews

The Tales of Hoffmann, English National Opera

The Tales of Hoffmann, English National Opera

A kitsch fantasy of a production brings the best out of Offenbach's opera

For all its comic fantasy and lilting tunes, there’s nothing pastel-coloured about Offenbach’s The Tales of Hoffmann. Deaths are frequent and bloody, humour is macabre, and emotions run high – being late to the pub is cause enough for violence and conspiracy theories. It’s a world of sliding screens, where a smile always threatens to become a leer, a kiss a murder.

There are few operatic comedies that don’t overstay their welcome; the quick thrust of good humour and opera’s wide-load pacing don’t always line up, and when they fail the result can be desperately tedious. The Tales of Hoffmann is always a risk in this respect. Lacking a definitive edition, at its longest the opera endures for a Wagnerian four to five hours, but with some brutal trimming can be reduced to a more manageable three. The compromise (based on the Michael Kaye/Jean-Christophe Keck edition but with changes including the Oeser ending to Giulietta’s Act III) currently being staged at English National Opera may err on the lengthy side, but thanks to Jones’s imaginative direction and Giles Cadle’s designs (not to mention one of the finest ensemble casts of the season) this psychedelic trip down the rabbit-hole never palls.

Barry Banks's Hoffmann is a fever of late-Romantic passion

The curtain rises on Hoffmann himself (Barry Banks), alone and struggling to write. His roar of frustration as he hurls yet another sheet of paper aside becomes the lowering orchestral opening, and as orchestral colour and pace gather we find ourselves abandoning the 19th-century world of the pub for an altogether more free-form sequence of worlds for the stories of Hoffmann’s three beloveds – Fifties kitsch for Olympia (“the little girl”), 19th-century Gothic for Antonia (“the artist”) and contemporary pop-art for Giulietta (“the reckless beauty”). Anchoring these adventures are Cadle’s designs, which each inhabit the same architectural space, reimagining the fixtures with dextrous variation.

This coherence of design, coupled with the authentic casting of a single singer not only for the three villains of the piece, but also for Hoffmann’s three loves (four if you count Stella), gives a welcome sense of through-direction and thematic coherence to a work that can so easily feel laboriously episodic.

This coherence of design, coupled with the authentic casting of a single singer not only for the three villains of the piece, but also for Hoffmann’s three loves (four if you count Stella), gives a welcome sense of through-direction and thematic coherence to a work that can so easily feel laboriously episodic.

Offenbach’s score might not stand up to close musicological scrutiny, but his gauzy melodies and bravura set pieces offer a grateful platform for singers. Leading the cast is a technically secure Barry Banks, whose Hoffmann is a fever of late-Romantic passion. From a poised “Kleinzach” he grew into the more sustained lyricism required by the Antonia and Giulietta episodes, offering not only his habitual beauty of tone, but rather more vocal weight that we’ve heard from him before. With Jones’s production undermining emotional authenticity at every turn, Banks struggled slightly with the arc of his hero – not a problem shared by young American soprano Georgia Jarman (pictured above), making her ENO debut as Olympia/Antonia/Giulietta/Stella.

Most at home in the coloratura rigidity of Olympia (her “Les oiseaux dans la charmille” was a triumph of vocal and choreographical precision), Jarman nevertheless made for an affecting Antonia (playing off against Clive Bayley’s Dr Miracle), and though the demands of Giulietta exposed the slightly pushed quality in her tone, this was a hugely convincing achievement for so young a singer.

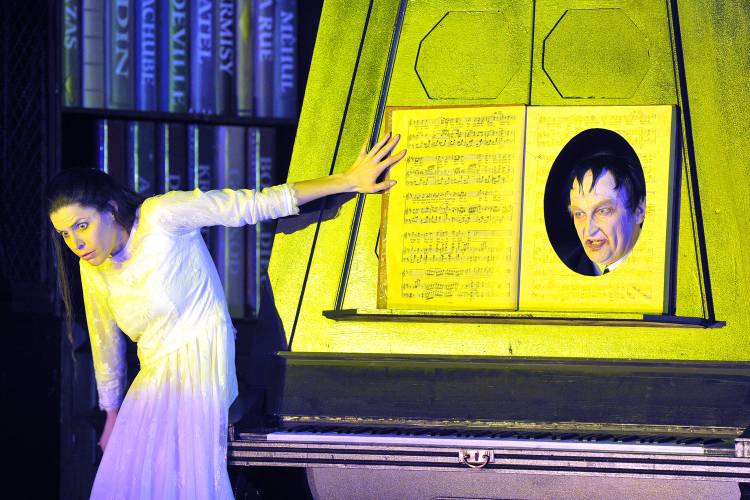

Support came in abundance from Bayley’s trio of villains (pictured left - does anyone do sinister quite as well as Bayley?), whose benign Coppelius gave way to the real menace of Miracle and Dapertutto, as well as from Simon Butteriss as the cross-dressing Cochenille and pirouetting servant (and artist manqué) Frantz. Yet even among the visual clamour of Jones’s staging and a universally strong cast, it was Christine Rice who stood out. This British mezzo just gets better and better, and here as Muse/Nicklausse it was the rounded beauty of her upper register that really shone, set off by the unlikely juxtaposition with her grinning Just William schoolboy persona – grubby knees, conker and all.

Support came in abundance from Bayley’s trio of villains (pictured left - does anyone do sinister quite as well as Bayley?), whose benign Coppelius gave way to the real menace of Miracle and Dapertutto, as well as from Simon Butteriss as the cross-dressing Cochenille and pirouetting servant (and artist manqué) Frantz. Yet even among the visual clamour of Jones’s staging and a universally strong cast, it was Christine Rice who stood out. This British mezzo just gets better and better, and here as Muse/Nicklausse it was the rounded beauty of her upper register that really shone, set off by the unlikely juxtaposition with her grinning Just William schoolboy persona – grubby knees, conker and all.

The Tales of Hoffmann will never be the greatest opera, but in Jones’s hands its weaknesses are celebrated – transfigured into brittle wit and even, on occasion, beauty. Yet among the chatter of cultural references (Disney vies with Manga and Banksy, and I still can’t place the gorilla who stalks the action in Act III) something gets lost. Perhaps partly the fault of Antony Walker’s rather woolly musical direction, this production lacks the violence so key to Hoffmann’s nightmare-vision. The stakes here are never quite real, and in sacrificing menace for surreal humour Jones blunts the fangs that peep out from the opera’s broad smile.

Buy

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Le nozze di Figaro, Glyndebourne review - perceptive humanity in period setting

Mostly glorious cast, sharp ideas, fussy conducting

Le nozze di Figaro, Glyndebourne review - perceptive humanity in period setting

Mostly glorious cast, sharp ideas, fussy conducting

Comments

Really enjoyed the in depth

I must correct a mistake I

Although I do not have any