Elgar's Enigma - A Love Child Named Pearl? | reviews, news & interviews

Elgar's Enigma - A Love Child Named Pearl?

Elgar's Enigma - A Love Child Named Pearl?

Tantalising evidence of the composer's secret double life as he composed The Kingdom

UPDATE 2015: Four years ago, in January 2011, I wrote this article about the music critic and biographer Michael Kennedy's search for the missing portion of Elgar's life. It identified a Mrs Dora Nelson as the composer's mistress and mother of a lovechild, who might have influenced some legendarily enigmatic aspects of Elgar's compositional output.

Michael Kennedy died on New Year's Eve 2014. He had given his enthusiastic approval to Baker's discoveries, as I reported in The Spectator. These discoveries have come tantalisingly close to definitive, but still need final proofs. My original article here for The Arts Desk set out the background to the mystery sparked by with Michael's letter from Sir Kenneth Clark, and how the search for Elgar's unacknowledged child arose.

THIS SUNDAY [January 2011] a period of gripping mystery in Edward Elgar's life will be summoned up when the LSO perform his oratorio The Kingdom at the Barbican. When he was struggling to write this devoutly religious work, going through something like a nervous breakdown, a young Welsh red-headed music-hall dancer was making her way on the stage. Were these events connected? More to the point, did Elgar have a lovechild with the dancer? Yes, was the answer given in private by musical circles. But the secret did not get out, while the evidence was allowed to die. Here, for the first time, the remarkable evidence that remains is laid out, in the hope that somewhere out there can be found a clinching piece.

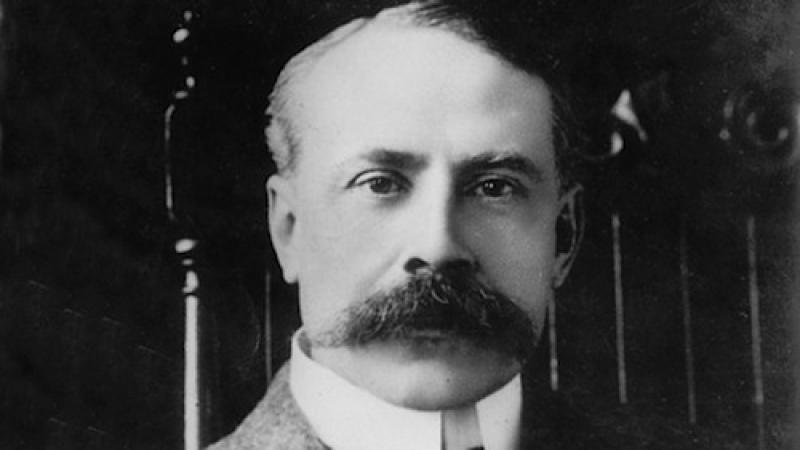

Elgar was always a man of riddles, as last November John Bridcut’s documentary, Elgar: The Man Behind the Mask, showed. The film pursued links between some of Elgar’s stranger, more potent music and his states of mind, seeded by a life of multiple layers and secrets. But potentially the greatest untold secret was not touched upon. Did Sir Edward Elgar have an illegitimate daughter? Further, was his secret love the muse who inspired the two mysterious dedications, never solved, in the 13th of the Enigma Variations and the Violin Concerto?

This is a story that has remained tantalisingly out of reach despite some significant pieces of tangential evidence that it is true.

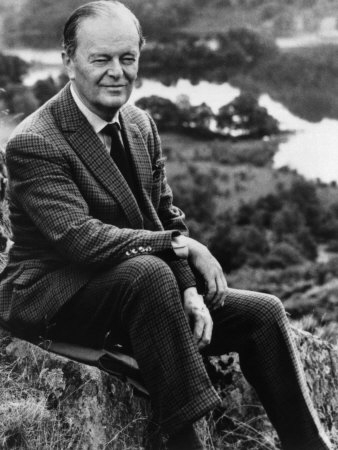

The eminent music critic Michael Kennedy was given the most crucial evidence that remains in a letter written to him by the historian and National Gallery Director, Sir Kenneth Clark (also maker of the landmark arts television series Civilisation). This sensational letter was prompted by the composer William Walton, who was not the only person to accept without doubt that the cook serving them at the palatial Clark residence had once been Elgar’s mistress, and that her daughter was his child.

Michael's article laid out the facts he knew, furnished him through his career as the doyen of music critics and major Elgar biographer

After many years of fruitless hunting for her, Kennedy wrote an article in The Sunday Telegraph, published Sunday, 15 November, 1992, headlined "The mysterious Mrs Nelson", appealing for assistance in finding corroborative evidence. I was the assistant arts editor at The Sunday Telegraph and working with Michael I subsequently pursued some of the research avenues it opened.

Birth certificates corroborate dates for the birth, as does Lady Elgar's diary of Elgar's visits to London at the critical time, but other supporting evidence from people who knew this at the time has not yet been unearthed.

Here, with Michael's approval, I am laying out a full summary of what we found and speculated, and what we have continued to discover of surrounding evidence. We hope that even at this very late stage (now with the help of internet communications) this largest of Elgarian mysteries may find a conclusive solution.

The Clark letter

Sir Kenneth (pictured below) had written to Michael in 1968, urged on by William Walton. As Director of the National Gallery and a knight while still only in his thirties, he was one of the highest panjandrums in British cultural life, and counted among his friends many composers, Walton, Constant Lambert and Alan Rawsthorne among them. He had met Elgar too, on his visits to London. On their household staff in the war the Clarks had had a cook, a Mrs Nelson, who was acknowledged by many in their circle as Elgar’s one-time mistress, and whose grown-up daughter was apparently accepted by them as being Elgar’s child.

Sir Kenneth recounted to Michael how he had been asked by Mrs Nelson to back up her daughter’s passport application for ENSA, the wartime entertainment troop, which identified her as “Miss Elgar”. He did so. This is his letter, in full:

Sept 13 1968, from B5 Albany, Piccadilly W1

Sept 13 1968, from B5 Albany, Piccadilly W1

Dear Mr Kennedy,

I am afraid I have been travelling about the country for some time and so have not been able to answer your letter to Lady Clark. During the war we had a cook called Mrs Nelson. She had been cook to Lord Berners and was an extremely good one. She had dyed red hair and the remains of considerable beauty, and in her youth had been on the stage in Paris. She claimed to have been a great friend of Jeanne d'Avril. She had a daughter, whose age appeared then to be about forty, who was also on the stage but without her mother's advantages. The daughter was acting with ENSA, required a passport, and I had to sign the necessary form. She said, and her mother confirmed, that she was a daughter of Elgar, and indeed her name appeared as Elgar on the passport. I only saw Elgar once or twice, but to judge by earlier photographs she certainly had a strong physical resemblance to him. I used to pretend that Mrs Nelson must have been one of the unknown characters in the Enigma Variations, but of course the dates are wrong, as the Miss Elgar whose passport I signed cannot have been born much before 1905.

Yours sincerely, (signed) Kenneth Clark.

After Michael’s story appeared in The Sunday Telegraph, I interviewed Alan Clark MP, Sir Kenneth’s son, who remembered as a boy being aware of Mrs Nelson’s widely known history with Elgar. The possibility appeared to fit chronology and various circumstantial evidence. When I began to research further, other things fitted too.

We made a great leap when we had contact from a Rupert West-Nelson who identified Mrs Nelson as his mother, and who had a much older half-sister. He was by then a man in his sixties who was attempting to fill in his own patchy family history, but he had had no idea of his half-sister’s possible paternal connection. He gave useful clues to hunt down at St Catherine’s House, then the office for birth, marriage and death certificates.

The musical reason to do so was that there was at least a possibility that this Mrs Nelson, a small, pretty Welsh actress with luxurious Titian hair, might be the mystery dedicatee of Elgar’s Violin Concerto and the famous three-asterisked variation in the Enigma Variations. Moreover, the illicit affair and the birth of a child might have been a significant cause of Elgar’s well-known but unfathomed nervous crisis at the time. This long drawn-out breakdown, while he was composing The Kingdom, has been the subject of intense interest in all Elgar studies ever since his death in 1934. It resulted in him, a staunch Catholic, ceasing to go to Mass and in a larger sense abandoning his church.

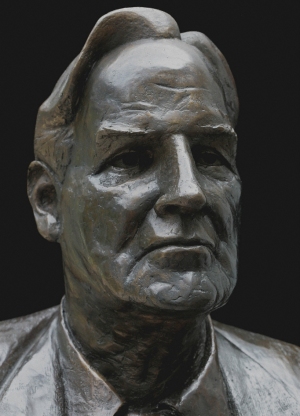

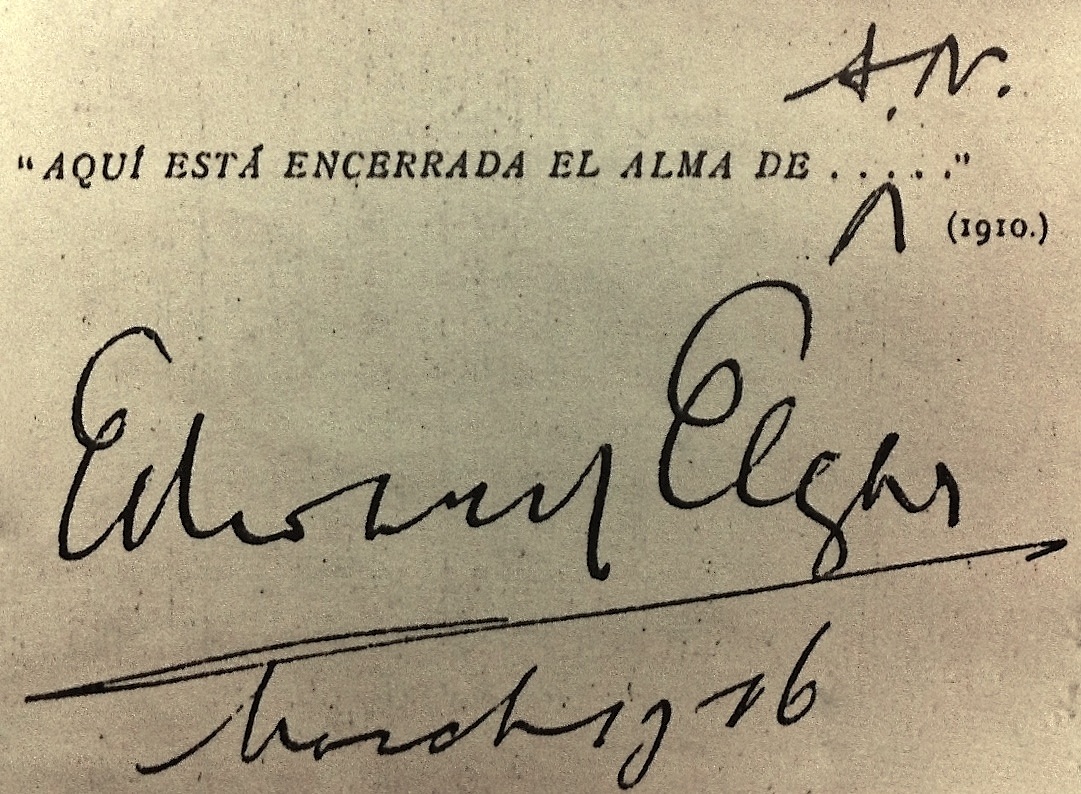

Michael’s article laid out for readers the facts he knew, furnished him through his lifelong career as the doyen of music critics and major Elgar biographer (portrait bust of Michael Kennedy, pictured right, by Cecile Elstein). He had two leading documents - the more important being the letter from Clark about his cook, but also a copy of the Violin Concerto inscribed by Elgar after a performance with the letters "A. N." over the five dots of the mystery dedicatee. This had belonged to a young violin student who had approached the composer after the concert - in later life she gave the score to Michael Kennedy.

Michael’s article laid out for readers the facts he knew, furnished him through his lifelong career as the doyen of music critics and major Elgar biographer (portrait bust of Michael Kennedy, pictured right, by Cecile Elstein). He had two leading documents - the more important being the letter from Clark about his cook, but also a copy of the Violin Concerto inscribed by Elgar after a performance with the letters "A. N." over the five dots of the mystery dedicatee. This had belonged to a young violin student who had approached the composer after the concert - in later life she gave the score to Michael Kennedy.

Elgar's assumed muse for the Violin Concerto has always been Mrs Alice Stuart Wortley, but the initials, reproduced in the Sunday Telegraph article, were much more obviously A.N. than A.W. (see reproduction below). If Elgar had indeed been serious when he inscribed those initials, it did not fit the standard wisdom.

Furthermore, Elgar had not even met Mrs Wortley when he composed the Engima Variations, and - for what it is worth - it was the strong view of two of his close associates, the music critic Ernest Newman and the conductor Leopold Stokowski, that one and the same woman inspired both works.

In sum, a plausible theory demanded researching. Elgar's *** in Enigma, written in 1899, and the "alma de ....." of the Violin Concerto, composed in 1909, have always been enigmas without solution.

In sum, a plausible theory demanded researching. Elgar's *** in Enigma, written in 1899, and the "alma de ....." of the Violin Concerto, composed in 1909, have always been enigmas without solution.

Rupert Nelson's mother was named Dora Adeline Nelson. DAN might be the three asterisks in the 1899 work and might also be the "A.N." Elgar inscribed on the concerto score. Her nickname Peggy, or that of her daughter, remembered by Rupert as Pearl, might also be the five dots in the 1909 work - the lovechild whom Sir Edward Elgar could never acknowledge. Just because they were lower-drawer than his other female associates did not mean that Elgar (a man clawing his way up from tradesman class) could not have felt the most regretful - and painful - love for them.

Even though John Bridcut’s film uncovered a love letter to Elgar from a young student written after his death, she was far too young to be the muse of 30 years before. After the film was broadcast, I asked Michael Kennedy for permission to reveal the full details of his long quest and my subsequent researches in a final attempt to see if further information might come to light. He agreed.

Listen to the 13th of the Enigma Variations, the LPO conducted by Daniel Barenboim (from ChrisWorthMusic on YouTube):

Dora Adeline Nelson

Sir Kenneth Clark’s employee during the war was a petite, characterful, well-spoken redhead by then nearing 60. Said to have been on stage in her youth, Mrs Nelson had later become a first-class cook, hired by very grand families around London, including Lord Berners, the noted epicurean, and Sir Oswald and Diana Mosley, as well as Sir Kenneth Clark.

Working from Rupert West-Nelson's clues proved a frustrating but eventually encouraging inquiry. He had grown up without much contact with his mother, and when he did so she told him little about her past. The names Dora and Nelson were common, Nelson being particularly widespread in Wales.

Working from Rupert West-Nelson's clues proved a frustrating but eventually encouraging inquiry. He had grown up without much contact with his mother, and when he did so she told him little about her past. The names Dora and Nelson were common, Nelson being particularly widespread in Wales.

A theatre actress named Dora Nelson appeared on an Ogden's Cigarette Card in 1900. Very pretty she looks. But it is unlikely, from the date, that this is the same Dora Nelson as his mother. Still it is certainly quite possible that a young dancer-actress might have become a mistress to Elgar on one of his trips away from his home in Great Malvern, Worcestershire, which he shared with his much older wife, Alice.

It was crucial to find a connection in the life of Dora Adeline Nelson, if Rupert's mother were the right woman. Born of Swedish background as Neilson, and raised in Wales, she was nicknamed Peggy as a child by her family, so her son told me. But when she left for London to go onto the stage, it is a reasonable guess that she would perform under one of her two Christian names. She was arriving in London just as another dancing Adeline, Adeline Genee, only a year older than herself, was becoming the latest sensation. Genee had named herself after the opera star Adelina Patti. It would be natural enough for the aspiring young Welsh dancer, on discovering the coincidence, to use her second name as well, perhaps in her social life to increase her shine. (Using a second name with acquaintances was a common enough practice - Mrs Elgar herself used Alice, not her first name, Caroline.) And if there was an established Dora Nelson in theatre already, it would be another reason to switch. Hence, it is not impossible that at the time Elgar may have been involved with her she was known to him as Adeline Nelson - A N.

At any rate, it is documented in official records that one Dora Adeline Nelson, when in her mid-twenties, bore a fatherless daughter discreetly in a home for unmarried mothers in south London in 1907. She named her baby identically to herself: Dora Adeline Nelson (which certainly didn't help in researches. Nor did it help that Miss Nelson, the mother, later became Mrs Nelson, without any traceable husband).

Two highly interesting circumstantial links fit this birth neatly into the "fact" of Sir Kenneth Clark's testimony. First, Sir Edward made two specific trips to London at precisely the time of conception, September 1906. Second, it is apparent that soon after the composer's death, Dora Adeline Nelson's tough working life took a marked step upwards - of which more later.

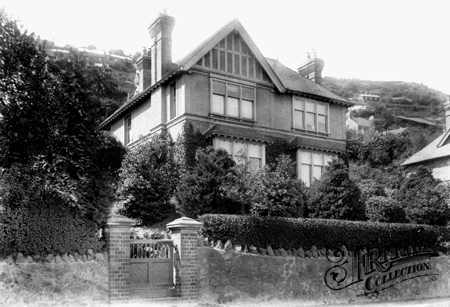

The scenario of a middle-aged, highly sexed Catholic Englishman having a fling with a feisty young dancer while away from home, and then being devastated by guilt on leaving her pregnant, is not inconsistent with either Elgar’s known predilections nor with the volatility of his emotions. (His Malvern home, Craeg Lea, pictured below in 1904.)

If he were indeed inspired by love with a young flame in 1899 (Enigma Variation XIII), and later mortified at abandoning her and her baby to inevitable oblivion (1907), this could be a cause for Elgar’s crisis of conscience and mental stability at the time - especially when trying to compose such elevated religious works as The Apostles and The Kingdom, with the tormented Judas figure at their heart.

If he were indeed inspired by love with a young flame in 1899 (Enigma Variation XIII), and later mortified at abandoning her and her baby to inevitable oblivion (1907), this could be a cause for Elgar’s crisis of conscience and mental stability at the time - especially when trying to compose such elevated religious works as The Apostles and The Kingdom, with the tormented Judas figure at their heart.

Nor would it be implausible that he should guiltily have the soul of his lost love and their young daughter at heart when he composed the Violin Concerto in 1909. Nor indeed would it be out of keeping with his allusive character that he might feel compelled to acknowledge it, if only in a private sidelong way, through penning the initials "A.N." on its score for a music student only a few years older than his lost daughter would be by then.

The secret survived, apparently kept on both sides, and nothing was suspected.

The rumours

However, the significant thing is that within 10 years of Elgar’s death, the very top drawer of society, Clark and Elgar's peer composers Alan Rawsthorne, William Walton and Constant Lambert, were all openly accepting "the known fact" of Clark's cook, Mrs Nelson, being Elgar's mistress and the daughter his illegitimate offspring. Clark even willingly put his signature to it on passport identity documents, as his letter to Michael Kennedy recounted.

Alan Clark MP, Sir Kenneth's son, told Michael Kennedy that it was "a known fact" among his father's musical friends, and much talked about. He gave me a few more details in a phone conversation in early 1993, after Michael's article appeared. He told me he was a schoolboy on holidays from Eton when he met Mrs Nelson at one of the family's homes, where they entertained in the grand style with a large staff. Alan Clark told me he thought Mrs Nelson had been with the family about eight months when he first became acquainted with her, though he could not remember which family house it was. Possibly Gloucestershire, possibly London. He did not remember seeing a daughter.

There was just a possibility of Mrs Nelson's daughter, Pearl, born in 1907, being still alive

"Pearl", Rupert West-Nelson's half-sister, was by now in her mid thirties, and married to an Enfield butcher. One must assume that her husband was on war service if she needed to renew identity documents and used any other name than her married one, Dora Puddefoot. If she was trying to get into ENSA, it seems likely she had asked her mother, a former dancer, to help her out with contacts.

When Michael Kennedy decided to write his article for the Sunday Telegraph, he needed others to help fill the jigsaw. He knew that Mrs Nelson would be long dead, but there was just a possibility of her daughter being still alive, in her late 80s. Rupert West-Nelson's letter gave a distinctive new direction for the investigation, which I, as the Sunday Telegraph's assistant arts editor, took up on Michael's behalf. In 1993 I did some interviewing and researching of birth, marriage and death certificates to identify more about his mother and her daughter through official records, but I ran aground after a few basic details.

Since that time, in new recent researches much aided by online resources, most of Mrs Nelson's extraordinary progress from uneducated Welsh girl to high-society cook, despite two illegitimate babies, can be discovered. But a connection between her and Elgar still lacks the clinching evidence. That there was a Mrs Nelson accepted as Elgar's mistress, and mother to his child, is attested by Sir Kenneth Clark's letter to Michael Kennedy. The question is how to confirm her identity.

Known facts about Elgar

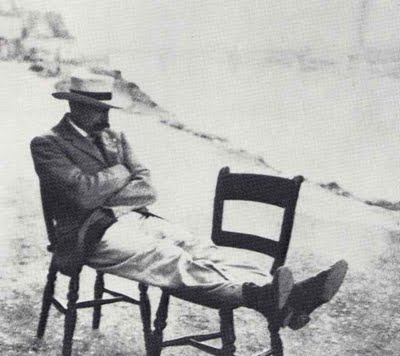

In 1889 Elgar, aged 31, married a woman of 40, Caroline Alice Roberts - a marriage generally accepted as a relationship of companionship rather than sexual passion. A year later, Alice bore Edward a daughter, Carice. (Mr and Mrs Elgar pictured right in 1891.)

In 1889 Elgar, aged 31, married a woman of 40, Caroline Alice Roberts - a marriage generally accepted as a relationship of companionship rather than sexual passion. A year later, Alice bore Edward a daughter, Carice. (Mr and Mrs Elgar pictured right in 1891.)- In 1899 Elgar wrote the Enigma Variations, dedicated to his friends, all easily guessed from their nicknames and initials. Yet there was a mysterious dedication of three asterisks *** over its 13th variation, a yearning, dreamily romantic piece.

- In 1904 Elgar was knighted.

- In 1905-7 Elgar had had something like a nervous breakdown. As he was a devout Catholic, it's been supposed that it was the stress of completing his religious oratorio The Kingdom, whose fitful progress had taken him five years or more. He wrote some of his strangest, most dissonant and nihilistic music in 1907.

- In June 1907 a child baptised Dora Adeline Nelson was born to a Dora Adeline Nelson in a charity maternity hostel in Wimbledon.

- In 1909 Elgar completed a violin concerto, premiered in November 1910 by the leading violinist Fritz Kreisler, and teasingly dedicated in Spanish "Aquí está encerrada el alma de ....." (Here is concealed the soul of) and five dots.

- In March 1916 after a performance of the Violin Concerto in Birmingham, a music student asked Elgar to sign her pocket score of the concerto. Over the five dots he wrote “A.N.”, signing it. It thus read: “Aquí está encerrada el alma de A.N." Decades later, that student gave the score to Michael Kennedy.

- In 1934, Elgar, on his deathbed, made a five-word remark to his friend, the leading music critic Ernest Newman, which Newman described later as "a distressing remark", "too tragic for the ear of the mob" and "[lending] itself too easily to the crudest of misinterpretations". Elgar's sickbed nurse reported that he had talked about a little girl in his last days.

- In 1939 Newman wrote to Clare Wortley, daughter of Elgar’s closest confidante, telling her of the deathbed remark, and asking her advice, agreeing with her not to reveal it.

- By 1944, and likely much earlier, it was common knowledge among Britain’s leading composers, and their friend Sir Kenneth Clark, the Director of the National Gallery, that Elgar had had an illegitimate daughter, and that the mistress was Sir Kenneth Clark’s cook. Sir Kenneth agreed to verify the daughter’s passport application, which bore the name "Elgar".

Known facts about the Dora Adeline Nelsons

- Dora Adeline Neilson born 1882, Newport, Monmouthshire, Wales, of Swedish emigrant stock

- April 1901, living in Wales, aged 18, now begins anglicising her surname to Nelson

- September 1906, becomes pregnant (probably in London)

- June 1907 bears a fatherless daughter in a Wimbledon charity hostel, named Dora Adeline Nelson

- April 1911, mother works as a servant in London while young daughter is in Wales, living with relatives

- Summer 1926, mother becomes pregnant aged 43 by the much younger Rupert West in London

- February 1927, mother bears an illegitimate son in London, named Dennis Rupert Nelson. The father is not named on the certificate (but the son confirmed to me who his father was)

- 1932, daughter, nicknamed "Pearl", marries an Enfield man

- 1934-6, mother works for a Hendon household

- 1937-9, a Mrs Nelson works for noted epicurean Lord Berners in Belgravia

- 1940s, this Mrs Nelson works for Sir Kenneth Clark - he signs her daughter's identity papers, and sees her passport says "Elgar". He is familiar with the "known fact" that mother was Elgar's mistress and daughter is his child

- 1944, in her sixties, Mrs Nelson works briefly for Sir Oswald and Diana Mosley in Newbury

- 1961, Dora Adeline Nelson (mother) dies in London, aged 79

- 1990, Dora Adeline Nelson Puddefoot (daughter) dies in Cornwall, aged 83

Speculation

This is a chronology of events which fits tantalisingly into a coherent emotional narrative, though it cannot all be proved.

In 1889 Elgar, aged 31, married Alice Roberts. Within a few years, however, the composer was vigorously tasting and pursuing success on many trips from Great Malvern to London on his own. It is possible that he met a 16-year-old aspirant dancer (or actress) named Dora Adeline Nelson touring in the West Country, or even as a servant, and fell for her bright, independent spirit and young glamour. It appears possible that she performed under the name Adeline, thanks to its celebrity association with Adeline Genee, though Theatrical World magazine in the late 1890s has a Dora Nelson shown in bit parts in comedy theatre. This may well be a different Dora Nelson, however, slightly older.

In 1899 Elgar wrote the Enigma Variations. It was gossiped straightaway that the 13th variation signified a secret love of Elgar’s, and that what was supposed a quotation from Mendelssohn's Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage referred to her having gone away. One could assume that his inspiration need not be a grande passion - simply to tease might be enough in a riddlesome composition dedicated "to my friends pictured within". The point would be whether an association begun then had lasted 10 years.

In 1905-7 the recently knighted Sir Edward had had something like a nervous breakdown, while taking a long time to complete The Kingdom, his companion oratorio to The Dream of Gerontius and The Apostles. From around that time Elgar seems to have virtually stopped going to Mass. What caused this personal crisis? Guilt? If so, about what, or whom? Did mental illness lead him to an adulterous relationship with a young woman? And what dark journey caused him in 1907 to produce that desolate, nihilistic song Owls, highlighted in John Bridcut’s film?

In 1905-7 the recently knighted Sir Edward had had something like a nervous breakdown, while taking a long time to complete The Kingdom, his companion oratorio to The Dream of Gerontius and The Apostles. From around that time Elgar seems to have virtually stopped going to Mass. What caused this personal crisis? Guilt? If so, about what, or whom? Did mental illness lead him to an adulterous relationship with a young woman? And what dark journey caused him in 1907 to produce that desolate, nihilistic song Owls, highlighted in John Bridcut’s film?

Meanwhile, for a few years into the new century, pretty young Dora Adeline Nelson from Newport, Wales, had gone to London to work in domestic service and then launched herself as a dancer in Paris, allegedly with the celebrated performer Jane Avril, Toulouse-Lautrec's frequent muse (who was a keen Anglophile). Dora Adeline was clearly an attractive and resourceful girl, and having shed her Welsh accent, she would not have lacked for admirers.

Yet she remained single evidently, because in 1907, aged 28, and presumably having had to abandon the stage, she bore a child in a charity home for unmarried mothers in South London.

When I went to St Catherine’s House in 1993 I found four Dora Nelsons were born 1904-1907, but one fatherless Dora Adeline Nelson, which was the full name remembered by her son Rupert. “June 15 1907: Dora Adeline born to Dora Adeline Nelson, General servant (domestic), at the residence 47 Haydons Rd, Wimbledon. No father named.”

Remarkably, Elgar made two visits to London at exactly the necessary time

If Clark was right about Mrs Nelson, when Elgar was putting the finishing touches to his oratorio The Kingdom, he was simultaneously tripping surreptitiously to his flame-haired young lover in London and getting her pregnant.

And there is the confirmation in his life. Remarkably, according to the Elgar Society's online timeline, using evidence from Lady's Elgar's diary entries, Elgar made two visits to London at exactly the necessary time, 3-7 September and 17-19 September.

If on one of his visits to DAN, she told Sir Edward she was pregnant, he would undoubtedly have been in an agonised battle with his conscience. Their liaison beforehand surely could not have left him unmarked by fear and guilt at his adultery, the more so if he was already torn by spiritual doubts through his deep immersion in the profound emotions of his oratorios.

Something certainly permeated to his wife, Lady Elgar, whose bitter verses about betrayal, evidently aimed at him, were brought out by John Bridcut's film.

Everything was at stake. Elgar had finally come into the status he had craved all his life. If this liaison did indeed occur, he would have known that a bastard child could mean the end of it, probably disgrace, and the curse of lifelong condemnation by the God whom he had spent several years building musical monuments to in epic and acclaimed oratorios.

One can only speculate how DAN and her child would have managed when it was clear that there was no question of the father being acknowledged. Evidently DAN was an honourable and robust woman, who swiftly got on with her new life in domestic service; whether she received any money from Elgar or other sources at that time we do not know.

But in 1909 Elgar picked up the violin concerto he had begun in 1905 and completed it. It was much publicised, premiered by the leading violinist Fritz Kreisler in 1910. In its mysterious dedication, "Aquí está encerrada el alma de ....." it is of incidental interest that there are five dots, not three, the standard form for printed ellipses. Were the dots deliberately five? For a name? If it were true - as Newman and Stokowski said - that one woman was at the centre of both the Enigma variation in 1899 and this concerto, there would have had to be an unusually durable cause for attachment over a decade.

The inscribed copy of the Violin Concerto that Elgar gave the student in Birmingham in March 1916 with the initials “A.N.” over the dots appears to be the only document existing in which Elgar gave any clue to the identity of the dedicatee. Though again, it might not be what it seems.

In 1920 Lady Elgar died (the Elgars' grave in St Wulstan's Roman Catholic Church, Little Malvern, pictured right). Two years later Carice Elgar married. It could be supposed that this left Sir Edward in an easier position to arrange support for an illegitimate daughter of 13, who by now had spent much of her short life in the privations of the First World War. He might even be curious to know whether she had inherited his music or her mother’s stage charisma.

In 1920 Lady Elgar died (the Elgars' grave in St Wulstan's Roman Catholic Church, Little Malvern, pictured right). Two years later Carice Elgar married. It could be supposed that this left Sir Edward in an easier position to arrange support for an illegitimate daughter of 13, who by now had spent much of her short life in the privations of the First World War. He might even be curious to know whether she had inherited his music or her mother’s stage charisma.

On the other hand he was locked into his global reputation, the lowly self-taught composer who had become a knight and member of the exclusive Order of Merit. Could he dare to make some provision for her, after his death?

The death-bed remark

In 1934, the dying Elgar made the leading remark that only his friend Ernest Newman, the musicologist and Sunday Times music critic, heard. It would have seismic implications.

Two years after his death Elgar's confidante and close intimate Alice Wortley died, aged 74. After a decent interval, in 1939 Newman wrote to her daughter Clare (herself middle-aged) of Elgar's last words to him. The correspondence appears to have involved two or three letters, and one can guess that Newman may have been attempting very cautiously to ask advice as to some possible obligation he felt Elgar had left behind.

In what is perhaps the third letter of the sequence, Newman wrote to Clare Wortley that "the whole facts of the case" had been told him by an "intimate" of both Elgar and the woman concerned. "There was only one woman behind the two pieces - and I am pretty sure I know the name," wrote Newman. "The details are very curious and sad. I'm glad you [Clare] agree with me that Elgar's secret should not be exposed to profane eyes." [My italics.]

This wording is curious in its implications: it has a degree of complicity within it that implies Newman was expecting from Clare a privileged knowledge of Elgar’s intimate affairs, and therefore also some advice on a sensitive subject that he himself felt unsure about. It implies, too, that Clare Wortley did not know the name of the woman in "the case" - so it could not be her mother, Alice Stuart Wortley, concerned in this delicate "case".

However, the last sentence of Newman's (italicised) is intriguing in its implication that a biographer and eminent music critic would acquiesce readily to the suppression (which Clare Wortley clearly advised) of something that could undoubtedly have allowed him to produce a massively publicised Elgar biography. He had already done the official Elgar monograph and was the obvious man for the first official "life" of Elgar. That sentence implies something agreed between them to be unprintable.

Newman may have hearkened to Clare's advice at the time - and presumably he took no action. But he did not necessarily hold his tongue.

The contenders for Elgar’s *** and .....

Elgar had many lady friends, and quite a gallery of flings were available to fit his mysterious unnamed dedicatees. Lady Elgar told Dora Penny ("Dorabella" of the Enigmas) that the woman behind the 13th Enigma variation was Mrs Julia Worthington, an American friend of the pair. But Michael Kennedy thinks she was putting Dora Penny off the scent.

Some years after Enigma, Elgar marked a sketch for it "LML" - it's often taken that this was Lady Mary Lygon (pictured right), one of his many female friends, who went overseas to Australia (hence the supposed quotation from Mendelssohn’s Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage ). But the intense, mystical poignancy of the music jars with the idea of a mere friendship. (Also, wouldn't a friend naturally mark it "ML" for Mary Lygon rather than the more formal LML for “Lady” Mary Lygon?)

Some years after Enigma, Elgar marked a sketch for it "LML" - it's often taken that this was Lady Mary Lygon (pictured right), one of his many female friends, who went overseas to Australia (hence the supposed quotation from Mendelssohn’s Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage ). But the intense, mystical poignancy of the music jars with the idea of a mere friendship. (Also, wouldn't a friend naturally mark it "ML" for Mary Lygon rather than the more formal LML for “Lady” Mary Lygon?)

In the 1880s the young Elgar had been engaged to Helen Weaver (a five-letter name), but she got tuberculosis and emigrated to Australia. Was this Elgar’s lifelong passionate regret? Yet why would it continue to haunt him a quarter-century later?

Mrs Alice Stuart Wortley, of all Elgar's women, was his closest friend and a particularly intimate confidante. She was the daughter of the painter John Everett Millais, who painted a famous portrait of her (pictured left). However Elgar first met “Carrie” Wortley, then 40, three years after the Enigma Variations were composed, which upends any idea of her being a double muse for both works. Yet he referred to the Violin Concerto in their extremely close and loving correspondence as "yours" or "our own". So are the letters that appear to be A.N. on the inscribed violin score actually A.W.? They look exactly like A.N. as reproduced in the Sunday Telegraph article.

Mrs Alice Stuart Wortley, of all Elgar's women, was his closest friend and a particularly intimate confidante. She was the daughter of the painter John Everett Millais, who painted a famous portrait of her (pictured left). However Elgar first met “Carrie” Wortley, then 40, three years after the Enigma Variations were composed, which upends any idea of her being a double muse for both works. Yet he referred to the Violin Concerto in their extremely close and loving correspondence as "yours" or "our own". So are the letters that appear to be A.N. on the inscribed violin score actually A.W.? They look exactly like A.N. as reproduced in the Sunday Telegraph article.

But it also might be questioned that Elgar would have fallen into mental crisis over her in 1906-7 when the indications are that their relationship only intensified after 1909, after the concerto had been dedicated. By that time Mrs Wortley (her husband became a baron in 1917) was in her late forties, Elgar a little older, and their friendship was several years old. She was also a good friend of Elgar's wife. If it was not illicit passion between them that caused this deepening of relations, but a mature bond between a flawed man and his trusted intimate, this appears to take Alice Wortley out of the frame as the muse.

But the mysterious Mrs Nelson, on the evidence we have, has as strong a claim as these. She was an entirely other type of girl from Elgar’s constrained aristocratic lady friends, and a susceptible middle-aged composer might indeed be lovestruck while away from his restraining home. It is also well conceivable that on her return to London in the mid-1900s, she and Elgar met again when he was in a highly emotional state, and a child resulted. Elgar, now Sir Edward (1904), might well have been devastated by allowing a surrender to carnality to result in a child he could not support openly - a serious offence indeed against morality as well as his new, longed-for social status. It is perfectly plausible that in such a situation a composer would sublimate his feelings in music, and enigmatically send his thoughts to her via secret dedications that perhaps only he would know.

Ernest Newman’s letters

Whether any of Elgar's friends knew about this is unclear, but it may well have come to light for the first time when Elgar was on his deathbed, and made that telling remark to his friend, the leading music critic Ernest Newman. The curious letter Newman wrote to Lady Alice Wortley's daughter a few years later raises considerable speculation. For one thing, it appears to indicate that Newman and Clare closed ranks and buried Elgar’s secret, whatever it was.

In Bridcut’s film, the Elgar specialist Michael Kennedy showed a tender letter from Elgar to Alice Wortley from which her daughter had scissored most of the back page, destroying whatever was in it. (Kennedy tells me that many of the "Windflower" letters had been similarly scissored by Clare.) Between two such soulmates what might be confessed? Possibly to Alice, and to no one else, would he confess his flaws, his worries about betraying his faith, or perhaps even his marriage. Perhaps he gave her hints that he knew he had behaved very badly, a long time before he had left a woman pregnant, and there was a child he had abandoned. God would not forgive him.

By the time Newman (pictured) chose to write to Clare, both her mother and Elgar were dead. But given Clare's protectiveness of her mother's reputation, and the overwhelming intimacy of Elgar's letters to her that Clare had possession of, one wonders how she received Newman's account of Elgar's deathbed remark, “too tragic for the ear of the mob” and "[lending] itself too easily to the crudest of misinterpretations".

By the time Newman (pictured) chose to write to Clare, both her mother and Elgar were dead. But given Clare's protectiveness of her mother's reputation, and the overwhelming intimacy of Elgar's letters to her that Clare had possession of, one wonders how she received Newman's account of Elgar's deathbed remark, “too tragic for the ear of the mob” and "[lending] itself too easily to the crudest of misinterpretations".

Was it that the remark was a shock revelation of a betrayed marriage? Was this the too tragic matter that Newman was asking one of Elgar's nearest and dearest to give her view of? Was it a charge to try to find this now grown-up child? One could indeed see how he would hesitate.

There would be the potential for a very great scandal indeed, and possibly the contamination of some of Elgar's most heartfelt and nationally loved work. He himself, a distinguished critic, might well have suffered a public backlash by revealing any such thing.

Clare appears to have counselled silence. “I am glad you agree with me...” he wrote, closing the matter.

Yet within only four or five years, we reach the perplexing point that Sir Kenneth Clark's letter records. He, William Walton, Alan Rawsthorne, Constant Lambert and other musical colleagues were all acknowledging that Clark’s cook was Elgar’s former mistress, and that her daughter was his child. Clark was even prepared to put his signature to that effect. Where did that belief come from, so soon after Elgar's death?

Most probably Newman was the source of the information, recounting to his musical friends Elgar’s last words

Most probably Newman was the source of the information, recounting to his musical friends in confidence Elgar’s last words. Maybe he worried that Clare Wortley's attitude was not the right one for history, or for the biography that he felt he had to abandon. At any rate, the "known fact" evidently found wide, if discreet acceptance within the highest cultural circles after 1939.

But perhaps there was a second, more difficult legacy that Newman could not deal with openly. Perhaps Elgar had not just asked Newman to tell the outcasts of his death, but had also left a letter for the old flame and the now adult daughter, to show they had remained in his guilty thoughts - or even had inspired these two mysterious musical dedications. If a secret mistress was his muse for two of his greatest musical masterpieces, this indeed would blow open all the obsessively constructed Elgar respectability should Newman reveal it. Better for the keepers of the flame of Britain's greatest composer that these should stay mysteries...

Well, such a heartbreaking story is not at all implausible. The problem is tying this speculation firmly to fact and documentation.

Speculating on Dora Adeline Nelson’s story (after Elgar)

One can find the birth certificates for Dora mother and Dora daughter, one can stitch together from references in biographies of Lord Berners and Diana Mosley the fine career and reputation that "Mrs" Nelson had achieved after Elgar's death. What remains shadowy is how she and Elgar launched any liaison, and how she may have been helped either by him or on his behalf by his friends. Further circumstantial evidence can be found from my conversations and correspondence with DAN’s late-born son, Rupert West-Nelson, whose own life had been fractured by war and an absent father of his own.

It is highly likely that the birth of the little girl ended any secret relationship between her mother and Elgar. What is certainly known, from her son and elsewhere, is that Dora Adeline Nelson’s short stage career must have been over, for she went into domestic service, initially as a “general servant”. Now known as “Mrs” Nelson, she parked her baby with relations back in Wales while she continued to work her way determinedly upwards around London. She may have been hoping for her daughter to show signs of her famous father’s talent - she probably would not dare tell her child or her family who he was.

Meanwhile she continued to attract men, one of them a much younger chancer called Rupert Joseph West, with whom unexpectedly - despite a 13-year age gap - she had a child in her forties in 1927: a boy who would become our second witness. Dora, then 45, was working as "refreshments-counter assistant", it says on the birth certificate. It was a lousy second choice.

Once again her child was born in a charity hospital and had no father named on the birth certificate, indicating that Joe West could not commit himself to regularise this unorthodox relationship. It was the Depression; Dora was no doubt in desperate circumstances. In the early 1950s Joe West was caught embezzling a charity and went to jail, said his son; prison was the last place he ever saw him. The boy grew up under his second name, Rupert, and took on the surname West-Nelson, uniting his parents’ surnames.

Perhaps the mother wondered if there would be some secret sign sent from Elgar’s will to acknowledge his daughter

Pearl was 20 when her brother was born, a plain, big-boned girl lacking her mother's spirited attitude - she probably helped look after the boy while their mother kept on working to support them, but she left to work as a domestic in Enfield, where she met her future husband, Daniel Puddefoot. There was a marriage certificate for her when she was 25: "July 29 1932: Dora Adeline Nelson, 25, spinster (profession blank), m Daniel George Alfred Puddefoot, 31, bachelor (profession Valet), in Edmonton district. Witnessed by Walter Puddefoot, father, a builder's storekeeper." Her marriage must have been a relief to her mother.

Two years after Pearl’s marriage, in 1934, the newspapers announced the death of Sir Edward Elgar. Perhaps then Pearl was told who her father was. Perhaps the mother wondered if there would be some secret sign sent from Elgar’s will to acknowledge his daughter - or some money, even.

At any rate, soon after Elgar's death, Mrs Nelson, by now in her fifties, suddenly started doing rather well for herself. From housekeeping in modest households in North London, she was swiftly working as a cook for aristocratic families, highly recommended, judging by her progress through the households of Lords and knights during the next two decades. And the boy Rupert West-Nelson had been accepted into King Edward's School in Witley, Surrey, a very exclusive charity school.

Mrs Nelson's employers now included Lord Berners, the Clarks and the Mosleys. Alan Clark told me he thought it was probably around 1943 when his family were living in Gloucestershire that he remembered her. Michael Kennedy, though, thought it might have been at their London house a year or two later. At any rate, by the late war Mrs Nelson's Elgar liaison was apparently so well known that she had no fear of asking this distinguished knight, the director of the National Gallery, to sign her daughter’s ENSA application with her "real" father's illustrious name. If only we could discover that application.

The son's story

I spoke to Rupert West-Nelson, when I followed up Michael's research in 1993. He had contacted Michael to say, he believed this might be his mother, whose life he was attempting to piece together. He told me on the phone: "Mother was a wonderful cook and she was a cracker, a good-looking woman, with a straight nose, but the left of her upper lip had a hole. I used to say to her, 'What's that?' She said, Peter clawed her - Peter was a cat. In the Thirties she had short cropped hair. She kept her glorious Titian hair for years - it was a foot long. When she cut it off she kept the tresses wrapped in tissue in a trunk. I used to take delight in going through her trunk. Since she lived in other people's houses, she kept all her bits and pieces in a trunk."

He said she was Welsh but didn't sound it; and Alan Clark also remembered the cook being Welsh. She constantly talked about the theatre, Rupert recalled; what plays were currently on, who was in them, what to see. She did not talk about her own past, he said. "My mother was much abused and always seemed to be on her own." He told me he had a photo of himself and his mother, DAN, from when he was around five or six, taken in Brighton, he thought. He said he had cut up most photos of himself and his mother, out of unhappiness. He had had a most unsettling life.

After four years in the Witley charity school, he and the other pupils were dispersed when the school was commandeered in 1941 by the Admiralty. Rupert was 14 and his schooling was over. He applied to the army, but his age was swiftly rumbled. He then did marine work at BOAC in Poole, then in 1944, aged 17 - at about the time when the daughter was having her forms signed by Kenneth Clark - Rupert joined the Navy. These were the happiest three years of his life, he said. After demob in 1947, he went to live with his father’s brother Arnold in Sudbury, until Arnold emigrated to Canada. He thinks it was his uncle who told him that he had a much older half-sister. He did not recall seeing his mother during the war except for once visiting her at her then employer's, Sir Robert Gillan in Guildford, when he was on leave. He recalled Sturges the gardener. Sir Robert had given him a photo of himself as a pilot.

He tried to track down his father, Rupert Joseph West, for whom his mother had named him; it was an unhappy encounter. His father was convicted of fraud against a charity in London, and Rupert found himself visiting him in jail. It was his last sight of his elusive father.

He had missed his mother very much, he said, as school and services took him one way and her employment took her another. It was, in his touching phrase, "a life of separations". She was not demonstrative but pleasant, though he had few memories of her as a child. He saw little of his older half-sister Pearl - a “shadowy” figure, he said. He remembered one of the rare occasions he saw her in the 1950s, when they both visited his ageing mother in Shepherd's Bush. She was tall and tidily dressed, he said. He knew her as “Pearl”, now Mrs Puddefoot, but otherwise little about her. He knew nothing of any Elgar connection.

The elder Dora lived with Rupert and his wife and children for a year until she became too frail for them to cope with. Pearl, ageing herself, was reluctant to take her mother on, and Mrs Dora Adeline Nelson went into an old people's home in Islington. She died in 1961, aged 83. Rupert then lost touch with Pearl. Much later he tried to track her down, without success. He himself did well; he married and had children. He died in Oxfordshire in 1998.

Pearl's story

It was not a close family, thanks to events. Even if she did not believe herself to be the unacknowledged daughter of Sir Edward Elgar, Pearl Nelson might well have harboured some bitterness towards her mother and towards fate. She was less attractive to men, and the chance to acknowledge her luminous parent was denied to her when he might have helped her life to be very different indeed. Her mother's lively love life probably brought young Pearl a sense of instability too. She had been parked out by the mother as a toddler, and no doubt suffered from the same lack of maternal demonstrativeness that Rupert regretted. Her likely childlessness (there is no indication of Dora Puddefoot having a child) could have increased her sense of life’s unfairness.

One presumes she must have asked her busy, distant mother at some point to tell her about her father. The mother might well have kept the secret until Elgar died, 1934, when Pearl was 27. Or she might have already revealed it on Pearl's marriage to Daniel Puddefoot two years earlier - but then, what pressure might have been put on her by the younger generation to pressurise, or even blackmail, Sir Edward into recognising it?

It seems more likely that DAN kept her secret. Maybe if she was helped by Elgar's circle in that career leap of hers in the Thirties, it was on condition of secrecy.

Did the daughter go into ENSA, as per Kenneth Clark's recall? I drew a blank in my research. Wartime records are too fragmented. Given that her marriage to Puddefoot endured till death parted them in the 1980s, it could only have been a stage-name. Perhaps it was suggested by the mother, as one chance to claim the Elgar name for herself. In war, much about the future must have seemed uncertain; one might claim what one could. Especially if it was already common talk around the dinner tables where Mrs Nelson cooked.

I wondered if Pearl ended her days in an old folks’ home, telling visitors grandly, “I am Sir Edward Elgar’s daughter and I used to be on the stage.” And they would say, "There, there, Pearl, dear." It would sound like a fantasy. But perhaps it was not.

Watch home movies of Elgar in old age (ElgarRareMovies on YouTube)

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Dunedin Consort, Butt / D’Angelo, Muñoz, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - tedious Handel, directionless song recital

Ho-hum 'comic' cantata, and a song recital needing more than a beautiful voice

Dunedin Consort, Butt / D’Angelo, Muñoz, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - tedious Handel, directionless song recital

Ho-hum 'comic' cantata, and a song recital needing more than a beautiful voice

Classical CDs: Dungeons, microtones and psychic distress

This year's big anniversary celebrated with a pair of boxes, plus clarinets, pianos and sacred music

Classical CDs: Dungeons, microtones and psychic distress

This year's big anniversary celebrated with a pair of boxes, plus clarinets, pianos and sacred music

BBC Proms: Liu, Philharmonia, Rouvali review - fine-tuned Tchaikovsky epic

Sounds perfectly finessed in a colourful cornucopia

BBC Proms: Liu, Philharmonia, Rouvali review - fine-tuned Tchaikovsky epic

Sounds perfectly finessed in a colourful cornucopia

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: A Mass of Life, BBCSO, Elder review - a subtle guide to Delius's Nietzschean masterpiece

Mark Elder held back from blasting the audience with a wall of sound

BBC Proms: A Mass of Life, BBCSO, Elder review - a subtle guide to Delius's Nietzschean masterpiece

Mark Elder held back from blasting the audience with a wall of sound

BBC Proms: Le Concert Spirituel, Niquet review - super-sized polyphonic rarities

Monumental works don't quite make for monumental sounds in the Royal Albert Hall

BBC Proms: Le Concert Spirituel, Niquet review - super-sized polyphonic rarities

Monumental works don't quite make for monumental sounds in the Royal Albert Hall

Frang, Romaniw, Liverman, LSO, Pappano, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - sunlight, salt spray, Sea Symphony

Full force of the midday sea in the Usher Hall, thanks to the best captain at the helm

Frang, Romaniw, Liverman, LSO, Pappano, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - sunlight, salt spray, Sea Symphony

Full force of the midday sea in the Usher Hall, thanks to the best captain at the helm

Elschenbroich, Grynyuk / Fibonacci Quartet, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mahogany Brahms and explosive Janáček

String partnerships demonstrate brilliant listening as well as first rate playing

Elschenbroich, Grynyuk / Fibonacci Quartet, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mahogany Brahms and explosive Janáček

String partnerships demonstrate brilliant listening as well as first rate playing

BBC Proms: Akhmetshina, LPO, Gardner review - liquid luxuries

First-class service on an ocean-going programme

BBC Proms: Akhmetshina, LPO, Gardner review - liquid luxuries

First-class service on an ocean-going programme

Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mania and menuets

The Hungarians bring dance music to Edinburgh, but Fischer’s pastiche falls flat

Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mania and menuets

The Hungarians bring dance music to Edinburgh, but Fischer’s pastiche falls flat

Classical CDs: Hamlet, harps and haiku

Epic romantic symphonies, unaccompanied choral music and a bold string quartet's response to rising sea levels

Classical CDs: Hamlet, harps and haiku

Epic romantic symphonies, unaccompanied choral music and a bold string quartet's response to rising sea levels

Comments

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

The initials on the score of

I have only just discovered

My mother was born in 1933 -

Hi Debbie, I am doing