theartsdesk at the Dubai International Film Festival | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk at the Dubai International Film Festival

theartsdesk at the Dubai International Film Festival

Few festivals involve such contrasts as Dubai's, where Emirati showboating and kitsch parties accompany some important Arab cinema

Dubai is a city that famously emerged from the desert, founded on oil and ambition, rising in an eruption of skyscrapers, luxury resorts and bling.

One might say that Gulf cinema is also trying to grow in a desert – a cultural one. Dubai is hardly known for its intellectual or cultural output; film doesn’t attract the same investment as real estate or tourism; and audiences attending the multiplexes in this city’s enormous malls are not given much of a taste for anything other than Hollywood.

There’s another issue, which is that the storytelling tradition in this part of the world, while rich, is an oral one, and filmmakers are still in the process of adapting that tradition into narratives that work on screen.

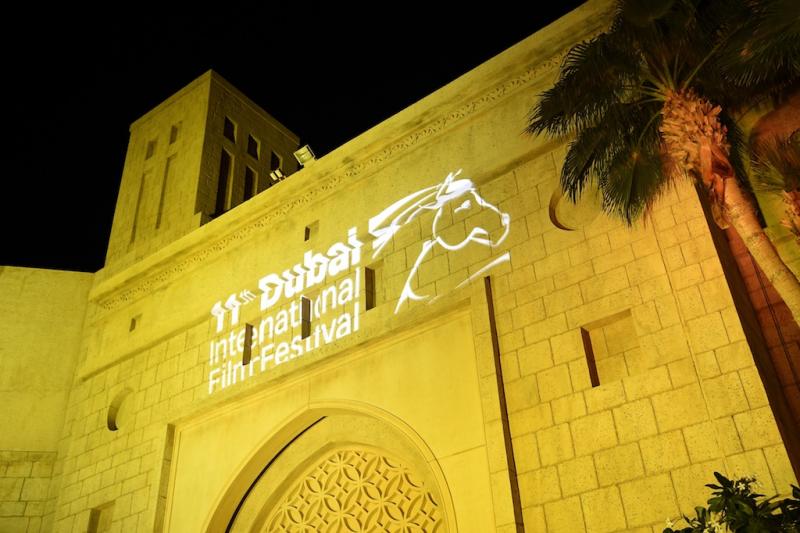

As in other regions in the world, for example Latin America, the film enthusiasts in the UAE have been answering this dilemma with film festivals, which offer both practical support and an all-important showcase for local filmmakers. There are now festivals in Doha and Abu Dhabi. But it was the Dubai International Film Festival (DIFF) that led the way.

There’s certainly a glitzy aspect to the festival that panders to the local elite

The idea for a festival in Dubai had been floating around from the 1990s. Then in 2001 two things happened that made it possible. One was the creation of the Dubai Media City – one of a number of cities-within-the-city that includes the Dubai Internet City and Dubai Healthcare City – which acted as a regional hub for news operations such as CNN and Reuters, and was attracting film production and post-production companies. The government asked the media city’s CEO, Abdulhamid Juma, to devise and lead its new film festival.

The other prompt was 9/11.

Recalls Juma: “After the tragedy of 9/11, everybody in the West wanted to know this part of the world – who are these people, Muslims, Arabs, why are they doing this? If you remember, in 2002/3 the Koran was one of the bestselling books, for that reason.

“So we said fine, let’s say who we are ourselves, rather than have others projecting the wrong image. Let’s enable our own filmmakers, our own people to tell their stories.”

DIFF's first edition was in 2004. And Juma certainly had his work cut out for him. “Dubai always wants the best, the biggest, the tallest,” he smiles. “And they wanted that from me in the first year.

“At the same time, the film industry was sceptical. ‘Not another film festival. In a city that doesn’t even produce films. Why?’ People thought it would be a PR thing, with stars and red carpets but no content. We had to strike the right balance between the glamour of what Dubai wanted, and building trust with the industry. This was the challenge thrown at us.”

There’s certainly a glitzy aspect to the festival that panders to the local elite – both the pampered Emirati and the wealthy expats and business people who lap up any opportunity to show off their designer labels and face jobs – and leaves the casual observer cold, if not downright appalled.

But on the film front, DIFF is succeeding pretty well. In its 11th edition, the international films (important in maintaining a festival’s connection to the wider film world and occasionally, though not this year, providing A-list guests) included The Theory of Everything, the screen version of Stephen Sondheim’s musical Into The Woods, and the scoop – immediately after its Australian premiere – of Russell Crowe’s directorial debut The Water Diviner. Crowe (pictured below) has done a very solid job with his sensitive and moving anti-war film, in which he plays a father determined to find the bodies of his sons, who died in Gallipoli, and take them home.

The real significance of the programme, however, is its Arab films, whose increasing number and prominence reflect the behind-the-scenes work of the festival in developing a local cinema, particularly through its Enjaaz post-production fund, which in a decade has assisted 240 Arab films, many of which are from the Gulf.

The real significance of the programme, however, is its Arab films, whose increasing number and prominence reflect the behind-the-scenes work of the festival in developing a local cinema, particularly through its Enjaaz post-production fund, which in a decade has assisted 240 Arab films, many of which are from the Gulf.

That said, Antoine Khalife, the director of the festival’s Arab programme, admits that the process towards making good films has been slower. “When we started to see these films, the subjects were not very interesting. All directors wanted to do was make a film – any film – and the content was pretty superficial.

“Now the subjects are deeper, the filmmakers really feel about the stories they are telling. They have something to say in terms of taboo issues, family problems, humanity in general. And they also understand that they have to have a very strong script before shooting.”

In truth, one still has to wade through some pretty awful fare, stories hampered by opaque narratives and pretension. Those that stood out, however, were very good indeed.

In truth, one still has to wade through some pretty awful fare, stories hampered by opaque narratives and pretension. Those that stood out, however, were very good indeed.

The excellent Yemeni drama I Am Nojoom, Age 10 and Divorced (pictured above) is based on a true story, in which a girl was married off to a 30-year-old man by her father, in a shoddy attempt to meet his debts. The film follows Nojoom as she is imprisoned in a village, where her treatment as a servant and sex slave is condoned by the older women, before the youngster finds a surprising and heartbreakingly bold way of saving herself.

Nojoom’s treatment is seen as an everyday aspect of tribal tradition, in a world where the only consideration is a man’s reputation – when Nojoom’s sister is raped by a neighbour, the recompense to the family is a couple of bulls – and the male characters are forever bleating about the shame brought upon them when a woman is wronged.

Though she has fictionalised the story, director Khadija Al-Salami brings her documentary experience to the table, eschewing melodrama for calm delivery of a story that speaks for itself. As shocking as it is, Nojoom’s experience is symptomatic of a problem that has resulted in thousands of child brides dying in Yemen.

The treatment of women is a major theme here. And the best film from the UAE, by a large margin, was a documentary. Nearby Sky follows Fatima Ali Alhameli (pictured below), the first Emirati woman ever to enter her camels into local auctions and beauty pageants – daring to take on one of her society’s many male bastions.

Fatima is a terrific character. An elderly widow of means and a Bedouin in spirit, most at home in the desert, she is feisty and very funny – whether constantly trying to hook up her male Sudanese assistant, declaring that camel milk is “ice cream for us Bedouins” and camel urine a cure for cancer, or lovingly shampooing her animals – which her sons suggest she loves more than them.

Fatima is a terrific character. An elderly widow of means and a Bedouin in spirit, most at home in the desert, she is feisty and very funny – whether constantly trying to hook up her male Sudanese assistant, declaring that camel milk is “ice cream for us Bedouins” and camel urine a cure for cancer, or lovingly shampooing her animals – which her sons suggest she loves more than them.

Yet Fatima is constantly knocked back by the event organisers, who feel that women should stay “behind the scenes”, her camels rejected from one event after another.

Director Nujoom Al Ghanem, an experienced documentary maker, paints a lovely relationship between mother and sons, while making one rile at the narrowness of a world in which even a beauty pageant for camels (surely an oxymoron) is infected by sexism. Her film is also ravishingly photographed.

I Am Nojoom and Nearby Sky won the best fiction and documentary feature prizes here.

Other commendable films included the Bahraini Sleeping Tree, about a couple struggling to cope with their daughter’s cerebral palsy, which had an emotional impact despite its poor structure, and Letter to the King, an ensemble drama concerning Kurdish refugees in Norway.

But when 80% of the population of Dubai is made up of expatriates, one does wonder who is watching these films.

“We do have a strange situation here,” Antoine Khalife wryly observes. “And when we began we didn’t know who was going to come to the theatres. Of course when you show a Lebanese film, for example, the Lebanese community comes. But the screenings are often full, and the audience is often mixed. For the foreigners living here it’s an amazing opportunity to learn something more about Arab life.”

Away from the Emirates, does Abdulhamid Juma feel that DIFF has fulfilled that aspiration to counter the negative images borne of 9/11?

“It remains a long journey. We’ve sent Arab films to more than 450 festivals, just to bridge that gap. And we sometimes invite film directors from very small US cities, in the hope that they may take one film back with them and show it to their audience in the middle of Alabama, say, so that people can see that Arabs are human beings too, they have the same issues, they want to educate their children, to have a better life, they want peace. If that happens every year, I think we are doing a good job.”

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

Add comment