Walter Becker, 1950-2017 - 'we play rock and roll, but we swing when we play' | reviews, news & interviews

Walter Becker, 1950-2017 - 'we play rock and roll, but we swing when we play'

Walter Becker, 1950-2017 - 'we play rock and roll, but we swing when we play'

In this interview from 2008, Steely Dan's co-founder talks about Donald Fagen, touring, jazz and solo albums

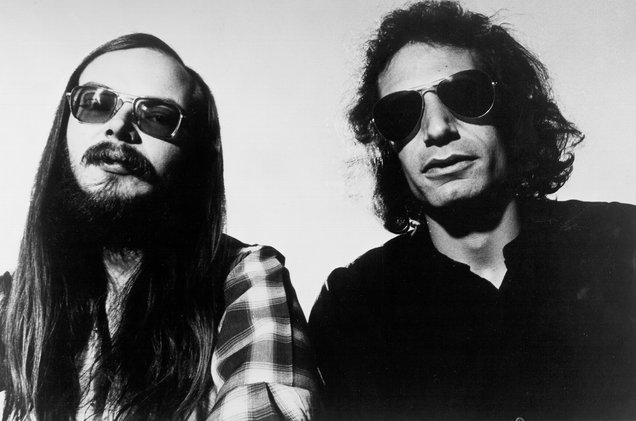

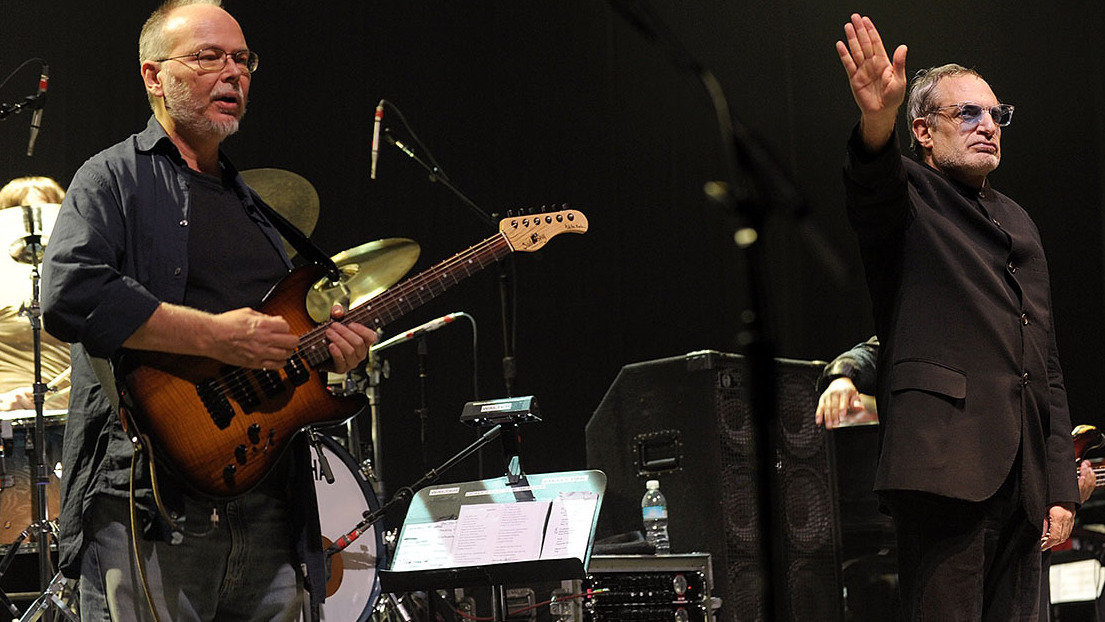

The death of Walter Becker last weekend brings to an end one of the great double acts of rock history.

The duo’s exacting standards meant that performing on a Steely Dan album was like taking part in a kind of musical Olympics, so as well as the brilliance of the songwriting, their albums are showcases of the studio musician’s art. "We play rock and roll, but we swing when we play," Becker explained. "We want that ongoing flow, that lightness, that forward rush of jazz."

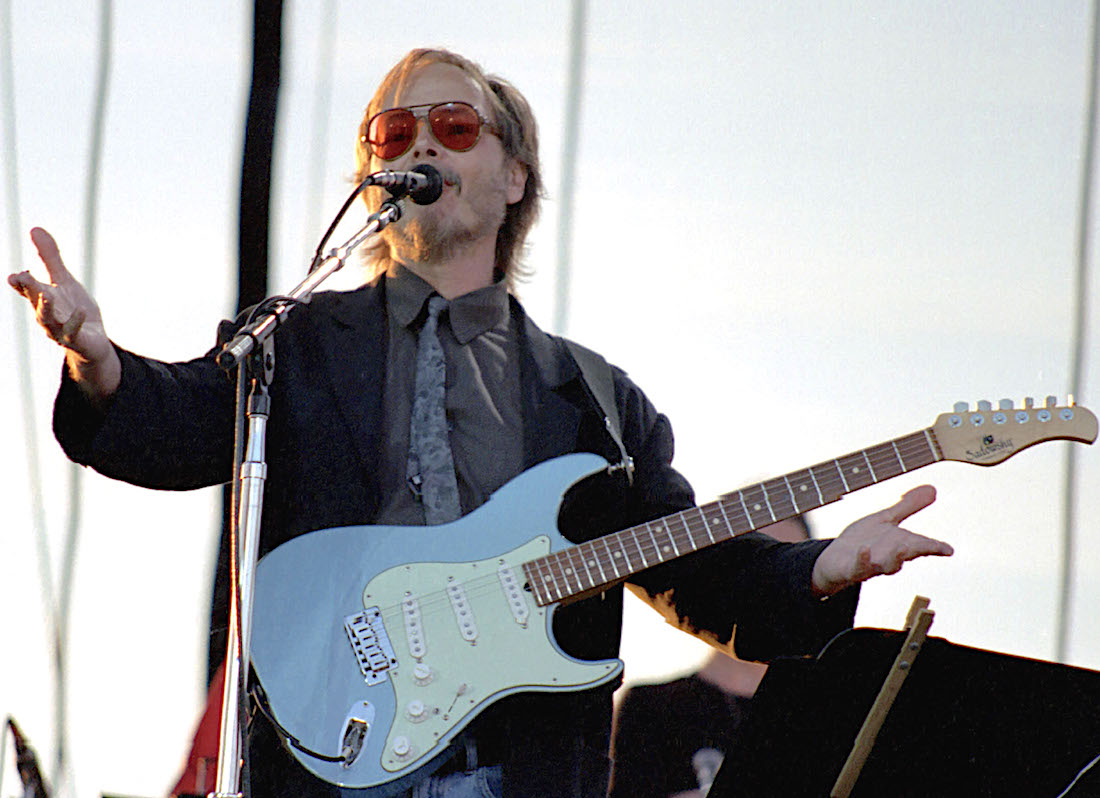

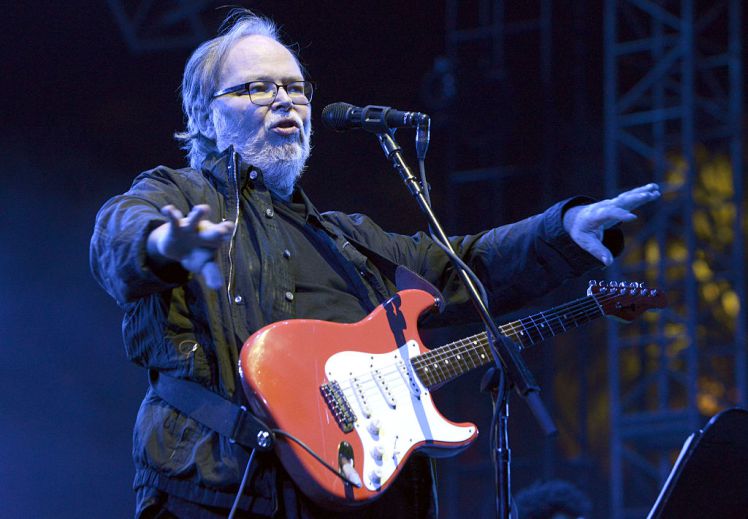

Becker, who originally met Fagen in 1967, when they were both students at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, was an accomplished guitarist as well as songwriter. He also racked up production credits with Rickie Lee Jones, China Crisis, Michael Franks and the Norwegian band Fra Lippo Lippi, as well as on Fagen’s 1993 solo album Kamakiriad. As a solo artist, he released 11 Tracks of Whack (1994) and Circus Money (2008), the latter partly inspired by rare and vintage recordings from Jamaica. This interview with Becker took place shortly before the release of Circus Money, backstage at New York’s Beacon Theatre, where he was performing a six-night stint with a stunningly accomplished touring version of Steely Dan.

Becker, who originally met Fagen in 1967, when they were both students at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, was an accomplished guitarist as well as songwriter. He also racked up production credits with Rickie Lee Jones, China Crisis, Michael Franks and the Norwegian band Fra Lippo Lippi, as well as on Fagen’s 1993 solo album Kamakiriad. As a solo artist, he released 11 Tracks of Whack (1994) and Circus Money (2008), the latter partly inspired by rare and vintage recordings from Jamaica. This interview with Becker took place shortly before the release of Circus Money, backstage at New York’s Beacon Theatre, where he was performing a six-night stint with a stunningly accomplished touring version of Steely Dan.

ADAM SWEETING: You used to hate touring so much so that you gave it up in the mid-Seventies. Was that because of the psychological issues of travelling with the same people all the time?

WALTER BECKER: There are many commonalities in the psychology of bands and band members that you find happening again and again. People dividing labour in certain ways, certain types of conflict evolving. It used to be the classic thing when we had the band in ‘70s, the potheads versus the juicers, those were the two most most salient divisions. A lot followed from that in terms of performance and what kind of mood you were in after the show and who said what and who kept quiet. Most bands didn’t last that long for those kinds of reasons, even hugely successful ones. It was understood when we started the band that Donald and I were going to run this band, we were gonna write the music and decide what songs to do and stuff like that and everybody would participate, but ultimately that was the concept. And eventually that became a problem, because frankly onstage some of the people were much more energetic than us and saw that as being equivalent to a making greater contribution to the success of the band. Now whether seeing a guy in a leather jacket with motorcycle flames painted on it leaping into the audience while I was playing struck me as a greater or lesser contribution is another question, but evidently that’s why we didn’t have a band any more. The ethos of the time lent itself to this idea of bands creating a sort of collective thing. The closest we came to doing that was with the second album, Countdown to Ecstasy, when we wrote the songs and showed them to the band members early on and arranged the songs with them in the studio, and that had a certain energy to it and it was great. So naturally we decided to do something completely different for the third album, with our unerring instinct.

Has the way technology has developed made touring more congenial and do-able?

Has the way technology has developed made touring more congenial and do-able?

Yeah it has, and professionalism, and just sort of organisational principles are elevated to a much higher degree. We used to travel with one or two guys who did everything – minus the sound company, who had their own people – and they humped all the gear, they didn’t have a truck, they used to get the gear onto commercial airlines as baggage and try to not pay for it. If stuff got bumped off the airplane you were just fucked. You’d get to the next town and your amplifier or whatever wasn’t there, so you’d rent whatever was missing or you couldn’t play. So now there’s like I dunno how many trucks and crew members and vast resources have been squandered… a giant swathe of rainforest has been cut down so that we and our fans can do whatever it is we’re doing this summer.

Was there any forethought in making your solo album and the Steely Dan tour coincide?

I would say as little as possible, because the album was actually finished about a year ago last February, and then we went on tour for the summer and so the minute it was finished I’d lost interest in it. I figured it was finished, now it’s somebody else’s job to go out and do all this stuff. Times being what they are in the music business that just didn’t happen, and some certain so-called record company that’s associated with a popular brand of coffee made some sort of offer that they later reneged on, which turns out to be the sine qua non of their business style. Anyway it didn’t work out and when I got home from the tour I finally said “why don’t we just license somebody to distribute this thing?” I don’t care, I’m not going to get rich selling these albums. There’s too much chaos in the scene right now. I don’t know overall if young musicians are in a worse position or a better position than we were in 40 years ago. When Donald and I were signed, the only reason was because a friend of ours [Gary Katz] who liked what we were doing became a producer there and said “just sign these guys, don’t even listen to their demos because you’re not gonna like it, you’re not gonna get it, just sign ‘em and that will be that”.

But if we had had to convince people in the ordinary way… we’d already tried that for years, and everybody said “we can’t sell these records, we can’t even play these records on the radio, much less sell them to anybody.” So I think in a way it’s not such a terrible time now. It’s too bad that a young musician can’t look forward to the idea that “well I’ll have an income and this is an ongoing business”, but I don’t know a time when that’s ever been the case actually, except for the tiny minority of us that were lucky and made careers out of it, and enough money that we could stay in one place and have families and have that kind of life. Not all the music that everybody makes is good, but music itself is still as powerful as it ever was. Not necessarily pop music, because pop has been turned into a fashion accessory and that’s what the record companies wanted to do, to create something that only had value for a season or two because that’s where they make their money. They make their money with kids who they just signed that they don’t have to pay, and then the careers of those kids are over and then some new kids come in that they’ve trained in their little music camp, y’know, their little boy band or girl band or little hooker-ette that they’ve taught to lipsync or do whatever.

But if we had had to convince people in the ordinary way… we’d already tried that for years, and everybody said “we can’t sell these records, we can’t even play these records on the radio, much less sell them to anybody.” So I think in a way it’s not such a terrible time now. It’s too bad that a young musician can’t look forward to the idea that “well I’ll have an income and this is an ongoing business”, but I don’t know a time when that’s ever been the case actually, except for the tiny minority of us that were lucky and made careers out of it, and enough money that we could stay in one place and have families and have that kind of life. Not all the music that everybody makes is good, but music itself is still as powerful as it ever was. Not necessarily pop music, because pop has been turned into a fashion accessory and that’s what the record companies wanted to do, to create something that only had value for a season or two because that’s where they make their money. They make their money with kids who they just signed that they don’t have to pay, and then the careers of those kids are over and then some new kids come in that they’ve trained in their little music camp, y’know, their little boy band or girl band or little hooker-ette that they’ve taught to lipsync or do whatever.

With the Circus Money album, you tried to record the tracks live as much as possible. That’s the complete antithesis of the way Steely Dan made records, isn’t it?

Literally in many cases that’s exactly true, but it hasn’t always been true. We’ve made many records where the band really just played, earlier on. So as time went on we got more and more into this sort of manufactured mode, and because it takes so long I had nothing to do while this incredibly tedious process was going on except to think about different ways, different things that were wrong with it. The biggest one being that nobody is playing with anybody else, nobody is responding to anybody else, there’s no musical communication, there’s no ebb and flow. You lay down something and then everybody is conforming their thing to that and you end up with something that sounds like it’s been manufactured. It can’t really breathe very much.

You and Donald must have had arguments about this, presumably?

You and Donald must have had arguments about this, presumably?

Yeah we did, and to some extent each of us was somewhat persuaded by the other. I think part of it has to do with letting things be what they are and what is better, is good better or is perfect better? To me good is better. Perfect is the enemy of the good in this case. I think to get good and perfect you need a lot of money and a lot of luck and a lot of different cracks at the ball and so forth. I could never afford to do it that way as a solo artist. With Steely Dan we used to have these huge budgets to make records and we could go in and track with bands all day and all night and then say “aah, this is all shit “, and not use it basically. So in other words what we got that was sort of good and sort of perfect was culled from this vast library of tracking sessions and so on.

Did drugs have anything to do with it? Was that way of working a cocaine-influenced trait?

No no, actually not. I would say not. I think this has to do with a personality thing. I think certainly the Seventies was an era of indulgence and discovery and so maybe you could make a parallel to the drug taking adventures and excesses and the results and some of things we did in the studio, but by and large Donald – who was and is more perfectionistic than I ever was – never took any cocaine. That had nothing to do with it. It had everything to do with an aesthetic ideal. If you listen to old big band records or old jazz records they’re monstrous, they’re so good. The way the bands played together and how tight they were. It’s a very high standard to shoot for and they had the advantage of having the band and travelling around with them and playing every night for year after year, same guys were in the band. Harry Carney joined the Duke Ellington band when he was like 20 and he stayed in it until he died. It was a job for life. We were trying to recreate things that were products of a process that was not available to us, so we did the best we could to simulate it.

You and Donald were both equally fanatical about jazz?

Oh yeah, that was our basic musical roots. I would say in the Seventies there was less of a dichotomy between the two of us, or less of a digression of tastes, than it became later on, but something that we both liked had to be good on many different levels. It had to not only be executed really well but it had to be harmonically interesting and all these other things, it had to be great in some way. And so we would just do things over and over again, we’d do guitar solos over and over again with different guitar players and stuff like that, not because there wasn’t something good about what those guys were doing but because it just didn’t ring the bell. For example, the song “Peg” turned out to be a very daunting thing for people to play over until suddenly this one guy came in and just played it. Every guitar player in town had played over this thing, and it just didn’t make sense to them. Then this guy just came in and he saw it the way we did it. Basically to me “Peg” was just a blues which somebody was going to play in a certain way, but because it had all of those cadences going through it and because it was a little bit of a weird length, it was very hard for people.

Did you study music theory?

Did you study music theory?

No, but working with Donald I did in a way. You basically realise there are certain chords you can play almost anything over. You can play blues notes over almost anything. If you listen to a Frank Sinatra record with a Nelson Riddle arrangement you hear all these weird little devices where suddenly part of the section will be unison muted trumpets and some flutes will play something in another key, and you know sort of what that is, it’s sort of meant to be an ironic reference. So what it boils down to is at some point anything goes, and you just try and find things. Part of my job as Donald’s partner was he would explain things to me. If he figured out some some new harmonic device or some trick you could do, he would show it to me and explain it to me, so when I wasn’t around he didn’t have anybody to explain it to. His wife didn’t know what he was talking about! At one point I was living in Hawaii and hadn’t worked with him for four or five years, and when we got back together he showed me all this stuff. He sent me a chart of different types of substitutions over different scale degrees and stuff like this. He had ldissected some Coltrane records and some Bill Evans records and read a couple of books and put together these new ideas. So for me that was like studying theory. I had private lessons. Student that I am, I absorbed only the idea of the thing and a few of the details, y’know. But enough to sort of get by.

- Walter Carl Becker, 20 February 1950 – 3 September 2017

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Album: Rise Against - Ricochet

Have the US punk veterans finally run out of road?

Album: Rise Against - Ricochet

Have the US punk veterans finally run out of road?

Music Reissues Weekly: The Final Solution - Just Like Gold

Despite their idiotic name, these San Francisco psychedelic pioneers sounded astonishing

Music Reissues Weekly: The Final Solution - Just Like Gold

Despite their idiotic name, these San Francisco psychedelic pioneers sounded astonishing

Mogwai / Lankum, South Facing Festival review - rich atmospheres in a south London field

Two polished performances and an embarrassment of instruments

Mogwai / Lankum, South Facing Festival review - rich atmospheres in a south London field

Two polished performances and an embarrassment of instruments

Album: Alison Goldfrapp - Flux

The synth diva in her comfort zone - maybe getting a little too comfortable, though

Album: Alison Goldfrapp - Flux

The synth diva in her comfort zone - maybe getting a little too comfortable, though

Album: The Black Keys - No Rain, No Flowers

Ohio rockers' 13th album improves on recent material, but still below mainstream peak

Album: The Black Keys - No Rain, No Flowers

Ohio rockers' 13th album improves on recent material, but still below mainstream peak

Wilderness Festival 2025 review - seriously delirious escapism

A curated collision of highbrow hedonism, surreal silliness and soulful connection

Wilderness Festival 2025 review - seriously delirious escapism

A curated collision of highbrow hedonism, surreal silliness and soulful connection

Album: Ethel Cain - Willoughby Tucker, I'll Always Love You

Relatively straightforward songs from the Southern Gothic star - with the emphasis on 'relatively'

Album: Ethel Cain - Willoughby Tucker, I'll Always Love You

Relatively straightforward songs from the Southern Gothic star - with the emphasis on 'relatively'

Album: Black Honey - Soak

South Coast band return with another set of catchy, confident indie-rockin'

Album: Black Honey - Soak

South Coast band return with another set of catchy, confident indie-rockin'

Album: Molly Tuttle - So Long Little Miss Sunshine

The US bluegrass queen makes a sally into Swift-tinted pop-country stylings

Album: Molly Tuttle - So Long Little Miss Sunshine

The US bluegrass queen makes a sally into Swift-tinted pop-country stylings

Music Reissues Weekly: Chip Shop Pop - The Sound of Denmark Street 1970-1975

Saint Etienne's Bob Stanley digs into British studio pop from the early Seventies

Music Reissues Weekly: Chip Shop Pop - The Sound of Denmark Street 1970-1975

Saint Etienne's Bob Stanley digs into British studio pop from the early Seventies

Album: Mansur Brown - Rihla

Jazz-prog scifi mind movies and personal discipline provide a... complex experience

Album: Mansur Brown - Rihla

Jazz-prog scifi mind movies and personal discipline provide a... complex experience

Album: Reneé Rapp - Bite Me

Second album from a rising US star is a feast of varied, fruity, forthright pop

Album: Reneé Rapp - Bite Me

Second album from a rising US star is a feast of varied, fruity, forthright pop

Add comment