theartsdesk in Tromsø: the celluloid Cold War | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk in Tromsø: the celluloid Cold War

theartsdesk in Tromsø: the celluloid Cold War

The Tromsø Film Festival in Norway has revealed some little-seen spy films from behind the Iron Curtain

With Russian spies murdering people in the UK, a Norwegian pensioner jailed in Moscow on spying charges, Russian hackers believed to have meddled in both the US presidential election and the EU referendum, diplomats thrown out of various countries and Donald Trump being portrayed as Putin’s puppet, it’s hard not to feel that the Cold War is being warmed up for the 21st century.

So while the spy genre is as busy as ever, this feels like an opportune moment to revisit or discover some of the best made during or about the Cold War period itself – from both sides of the Iron Curtain. The Tromsø Film Festival in Norway has duly obliged; while its Cold War: Moving Pictures sidebar consisted of just eight films, these offered a fascinating and rich glimpse into the cinematic spy game at a time when the real-world stakes were at their greatest.

There’s always a quality and mischief in the Tromsø programming, with both attributes in evidence here. The fact that the viewing takes place in sub-zero temperatures inside the Arctic Circle and in the midst of the Polar Night just added to the atmosphere. Norway’s biggest film festival, Tromsø attracts thousands of Norwegians, many from other parts of the country, for a wide-ranging programme of films. While many of this year’s audience will have seen the Bond entry, From Russia with Love (1963), far fewer would be acquainted with one of the greatest films of the genre, Martin Ritt’s The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1965).

The novel that made John le Carré’s reputation was brilliantly adapted to the screen, with Richard Burton (pictured above, with Oskar Werner) giving one of his finest performances as Alec Leamas, the British agent pretending to defect to the Russians but unaware, himself, of just how tricky his own masters can be. Shot in black and white and seeped in wintry gloom, the film conveys a world of grimly amoral expediency. As Leamas’s boss, Control, puts it: “You can’t be less wicked than your enemies, just because your government’s policies are benevolent.” Leamas doesn’t feel that benevolence, just a game played out by “seedy, squalid, bastard spies”.

From Russia with Love is one of Sean Connery’s best outings as 007, and one of the few Bonds squarely aimed at the Cold War, albeit with the criminal organisation Spectre playing the British and Soviet intelligence agencies against each other. It also features one of the most memorable Bond villains, the former Russian agent Rosa Klebb, she with the poisoned blade in her shoe.

Le Carré and Fleming offered two contrasting approaches to spy fiction: the former covering the procedure of the Cold War spy game, the grey apparatchiks in London and Moscow, the paranoia elicited by traitors and moles; Fleming a glamourous escapist version, dominated by machismo, gadgets and girls. The same variety could be found in the Eastern Bloc selections in Tromsø, though if anything there is a greater emphasis on entertainment.

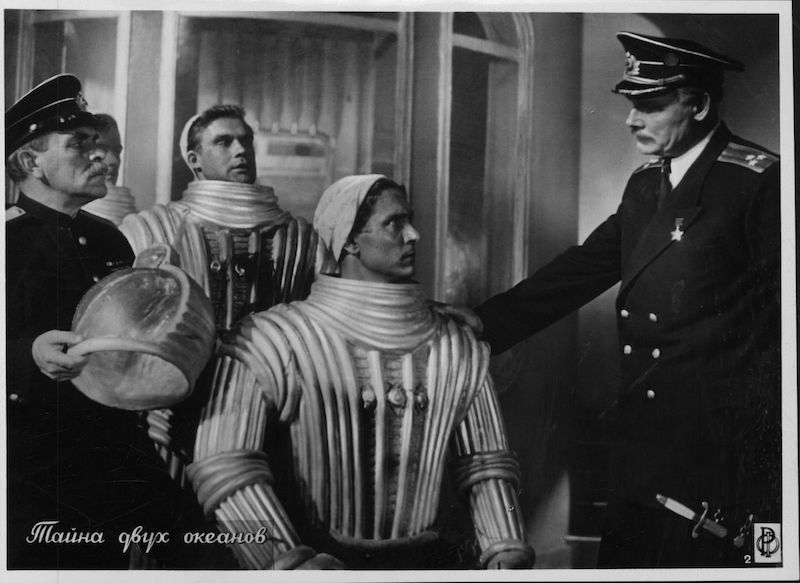

The Secret of Two Oceans (USSR, 1956, pictured left) is an astonishingly odd film, a sort of espionage sci-fi. Two ships are mysteriously sunk, one in the Atlantic, the other in the Pacific. The Soviet submarine Pioneer sets off to investigate. But there is a spy on board, determined to thwart its mission.

The Secret of Two Oceans (USSR, 1956, pictured left) is an astonishingly odd film, a sort of espionage sci-fi. Two ships are mysteriously sunk, one in the Atlantic, the other in the Pacific. The Soviet submarine Pioneer sets off to investigate. But there is a spy on board, determined to thwart its mission.

The film moves between atmospherically shot skulduggery on land, as the police try to capture the spy’s slippery accomplice, and the action at sea, where the futuristic sub tackles sea monsters, icebergs and manmade threats with a dazzling array of weapons. Its hammy fantasy is slightly reminiscent of the Sixties US TV series Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, but equally striking is the realistic aura of Cold War paranoia, with everyone a suspect, and no-one ever as he or she seems.

“That paranoia is what’s so important for me in this film,” says Tromsø’s artistic director Martha Otte, “and it’s made even more real because the enemy is never named.” Indeed, neither America nor any other capitalist country is mentioned, merely “a new master” intent on “a new war”.

Sergey Lavrentiev, the Russian film critic and curator who co-programmed the spy strand alongside Otte, says there’s a reason for this. “After Stalin died in ’53, Khrushchev started a new period of cooperation with the West [the ‘Khrushchev Thaw’]. So it was a question of politics, that’s why the film became some sort of science fiction, where you don’t know who the bad guys are. And it looks a little like James Bond before Bond.”

The Kremlin’s needs and predilections at any given time inevitably had an effect on film production. Hence Case No 306 (pictured right), also released in the Soviet Union in 1956. This time the genre mix is with the detective thriller. Lavrentiev again explains. “Stalin was a film buff, who favoured westerns – but hated detective stories. He insisted that there was no need for policemen in wonderful, crime-free Soviet society. Crooks, scoundrels, they all lived in the capitalist world.”

The Kremlin’s needs and predilections at any given time inevitably had an effect on film production. Hence Case No 306 (pictured right), also released in the Soviet Union in 1956. This time the genre mix is with the detective thriller. Lavrentiev again explains. “Stalin was a film buff, who favoured westerns – but hated detective stories. He insisted that there was no need for policemen in wonderful, crime-free Soviet society. Crooks, scoundrels, they all lived in the capitalist world.”

No surprise, then, that Case No 306 was put into production after the tyrant’s death and proved extremely popular with Russian audiences. Deservedly so.

It starts as a hit and run, thrillingly shot and edited, which leaves a traffic cop dead and an elderly woman fighting for her life. A male detective and his female forensic sidekick investigate. The moody black and white cinematography, the story’s dark tone and the fact that the handsome ‘tec looks a little like Glenn Ford all lend this a slightly noirish air, which only increases as the plot becomes as baffling as The Big Sleep.

A quality that’s all the film’s own is the spying sting in the tail, which sneaks out of nowhere. And free now to acknowledge a criminal fraternity, director Anatoly Rybakov lends a tongue-in-cheek social commentary: when the henchmen discover that their boss isn’t a criminal, but a spy (again unspecified, but likely to be West German), they’re positively outraged.

Made when the Bond movies were in full swing, The End of Agent W4C (Czechoslovakia, 1967), is wonderfully silly and effective spy spoof which, in keeping with all good parodies, both sends up and revels in the tropes of its target. It’s much funnier than a spoof from the West of the same year, Casino Royale. And it shows a smug capitalist spy becoming slowly unstuck in the East, the giveaway title suggesting the inevitability of this particular Cold War result.

The eponymous French agent (Jan Kačer, above right) has the far from imposing name of Cyril and a code name one numeral removed from a lavatory. Yet he’s portrayed as even more suave than Bond, turns female heads wherever he goes (despite the annoying trait of never removing his sunglasses), gets the measure of any room within seconds, and appears impervious to danger.

Armed with one all-purpose gadget, an old-fashioned alarm clock whose many functions includes that of a small atomic bomb (the agent needs to take care, himself, not to correct the time) W4C is dispatched to Prague in search of microfilm containing plans for the “military utilisation of Venus”, no less. Enemy agents fall like flies around him, all except an accountant drafted into the field with his dog, a Clouseau figure who will triumph despite himself.

Director Václav Vorlíček really has the measure of the genre he’s sending up, combining slapstick with the surreal and some very sharp commentary on the self-serving, naval gazing and arguably fruitless nature of the spy game.

Far more serious is the Hungarian documentary The Life of an Agent, made for TV in 2004 but comprised of archive material from between 1957 and 1988, discovered in the vaults of the Hungarian secret police after the fall of Communism. Specifically, these are excerpts from secret service training films, in which agents are designed in all things related to civilian surveillance – snooping on their own citizens.

This of course was a norm in Eastern Bloc countries, well documented and perhaps best depicted on screen in the German drama from 2006, The Lives of Others. But with chapter headings such as, ‘Where do you put the bug?’ and ‘Introduction to raiding homes,’ and detailed intel on interrogation, surveillance, home searches and the recruitment of informers (including the use of blackmail), the compilation brings home the distressing nuts and bolts of a society “shaped by compulsory paranoia.”

All the cliched tropes we’ve come to know largely through fiction – the camera hidden in a bag is a good example – are shown to be all too real. There are some new tips, to this writer at least, such as the importance of wearing felt slippers when snooping around someone’s house, and how to use the “bistro” table to prop up your concealed camera – one wouldn’t want blurry photos of your unsuspecting victim, after all. We’re told that there were 20,000 agents during the Kádár regime in Hungary, with thousands more collaborating in some form or other, and some 100,000 people under their gaze. By showing this in-house, how-to guide to repression, director Gábor Zsigmond Papp chills the blood.

The remaining two films on offer were the excellent 2009 French drama Farewell (starring Guillaume Canet and Emir Kusturica, pictured right), based on a true story from the Eighties involving a KGB colonel who smuggled thousands of secret documents to the West via a French engineer stationed in Moscow, which shows how the primary mechanism of espionage – deceit – will infect all aspects of a spy’s life; and Orion’s Belt (1985), a disposable Norwegian thriller in which the crew of a ramshackle cargo ship stumble upon a Russian listening station and suffer the consequences.

The remaining two films on offer were the excellent 2009 French drama Farewell (starring Guillaume Canet and Emir Kusturica, pictured right), based on a true story from the Eighties involving a KGB colonel who smuggled thousands of secret documents to the West via a French engineer stationed in Moscow, which shows how the primary mechanism of espionage – deceit – will infect all aspects of a spy’s life; and Orion’s Belt (1985), a disposable Norwegian thriller in which the crew of a ramshackle cargo ship stumble upon a Russian listening station and suffer the consequences.

The latter at least shows how the Cold War could infiltrate even a less than super power such as Norway. And Martha Otte says that with the former Norwegian border guard Frode Berg still in jail in Russia, “the Cold War theme definitely feels relevant right now for our region. His experience feels like a throwback to the bad old days.”

Other than mixing up the tone of the selection (realism, glamour, humour) Otte's aim was to try to make audiences think about the tension between superpowers and, further, “to offer a reflection on how film affects our perception of other peoples, other countries, even of who the enemy is.”

And the relevance of the selection has echoes elsewhere in Tromsø’s programme, not least in Werner Herzog’s documentary Meeting Gorbachev (2018). Here the USSR’s last president – a key figure in the end of the Cold War – clearly warns of a return to those dangerously frosty times. He’s not the only one looking over his shoulder.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

London Film Festival - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

London Film Festival - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

theartsdesk Q&A: Idris Elba on playing a US President faced with a missile crisis in 'A House of Dynamite'

The star talks about Presidential decision-making when millions of lives are imperilled

theartsdesk Q&A: Idris Elba on playing a US President faced with a missile crisis in 'A House of Dynamite'

The star talks about Presidential decision-making when millions of lives are imperilled

Urchin review - superb homeless drama

Frank Dillane gives a star-making turn in Harris Dickinson’s impressive directorial debut

Urchin review - superb homeless drama

Frank Dillane gives a star-making turn in Harris Dickinson’s impressive directorial debut

Mr Blake at Your Service review - John Malkovich in unlikely role as an English butler

Weird comedy directed by novelist Gilles Legardinier

Mr Blake at Your Service review - John Malkovich in unlikely role as an English butler

Weird comedy directed by novelist Gilles Legardinier

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight review - vivid adaptation of a memoir about a Rhodesian childhood

Embeth Davidtz delivers an impressive directing debut and an exceptional child star

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight review - vivid adaptation of a memoir about a Rhodesian childhood

Embeth Davidtz delivers an impressive directing debut and an exceptional child star

Add comment