A Previn treasury | reviews, news & interviews

A Previn treasury

A Previn treasury

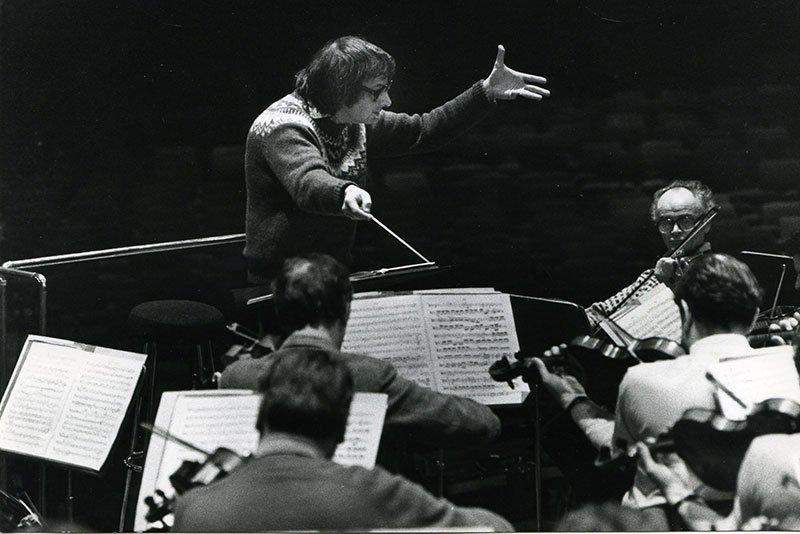

Selected recordings of the great musician, who has died just short of his 90th birthday

In a way, he was a second Bernstein.

Something of the fire had gone out of his conducting by the time I met him in his Reigate retreat in 1988 to talk about his Beethoven symphonies cycle with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (though he spoke passionately and in detail about the change in his attitude to Beethoven and his scorn for the period-instruments movement: "the idea of having to go overtime in order to make sure everyone plays out of tune is beyond me!"). Yet the heyday of the 1960s and 70s has left us a legacy of great recordings, his partnership with the London Symphony Orchestra very much at the centre.

A Jewish refugee from Nazi Berlin, turned away after three years as a piano student at the Hochschule, the nine-year-old and his family arrived in America by way of Paris in 1939. From New York they went to Los Angeles, so it was only a matter of time before the Wunderkind became involved with Hollywood as film composer and arranger; his first score was for The Sun Comes Up, a film with very little dialogue and Lassie appearing alongside Jeanette MacDonald in her final singing role on screen. His best soundtrack, I think, is for Elmer Gantry (1960); he told Edward Seckerson that at the time of composing it he'd just discovered Hindemith's Concert Music for Strings and Brass; it tells not only in the orchestration but also in the introduction. If that also sounds like Walton, soon to become another Previn speciality, that's because Walton too was under the spell of the German master.

At the same time he was playing Beethoven piano trios with Josef Szigeti, and had a reputation as a jazz pianist. Both parallel careers blossomed after the war. Among his best jazz versions are LPs devoted respectively to Weill and My Fair Lady (the full score of which he also re-arranged for the film). A personal choice here would be Rodgers and Hart's "Nobody's Heart" with another successful crossover, Leontyne Price. The slip into cocktail-bar piano at 1m45s is cool indeed.

By then (1967) his talents as a conductor of the late romantic and 20th century orchestral repertoire was established in a series of RCA recordings, most groundbreaking among them an electrifying interpretation of Walton's First Symphony which gave the work a new lease of life (the same happened with the series of Vaughan Williams symphonies). It was hardly surprising that Previn was the choice to conduct the composer's 80th birthday concert culminating in the riotous drama and ultimate celebration of Belshazzar's Feast (starting at 43m37s), happily to be heard if not seen in its entirety on YouTube (a DVD exists of both sound and vision, an invaluable document).

Three years after his 1965 recording of Shostakovich's Fifth with the LSO, he became the orchestra's chief conductor. He took them to some unexpected places – not least to the TV studios for weekly Saturday filmings of André Previn's Music Night. I remember so much of the then relatively unfamiliar repertoire well: Butterworth's The Banks of Green Willow, Ravel's La Valse, the second suite from Falla's The Three-Cornered Hat. At that point I was a bit young for regular concert-going, but I treasured the LSO recordings, made in the vintage days of a great EMI/HMV team, producer Christopher Bishop and balance engineer Christopher Parker. I got to know the complete Tchaikovsky ballets as grand, lush symphonic entities. Previn's preference for slow tempi meant that certain movements like this one from The Nutcracker were carved in my mind as the only way to do it; now I know otherwise, but I’m still fond of his take.

It seems extraordinary, now that snobbery about the Russian masterworks is a thing of the past, to find Previn taken to task by one American critic for being a "first-rate interpreter of second-rate repertoire". No-one thinks that way about his definitive Prokofiev now, and thanks partly to his championiship of an uncut Second Symphony, Rachmaninov's stature as a master symphonist went up several notches.

He left his post at the LSO after 11 years, but returned to become Conductor Laureate in 1993, and after 2016, Conductor Emeritus. Only one performance stays firm in my memory from those days, of Strauss's Eine Alpensinfonie. One might also question whether with the Vienna Philharmonic he became a "second-rate interpreter of first-rate repertoire". Some edge was also lost in performances with the Pittsburgh Symphony and Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestras (though there's a Pittsburgh Mahler 4 which is an absolute gem). His own concertos for a range of artists, including fifth wife Anne-Sophie Mutter, and his opera based on A Streetcar Named Desire, seem less likely to stand the test of time than his film music. But still, what a rich legacy from over 40 years of his creative life. And, very well, then, just as a silly encore, That Clip of Mr Preview.

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

Comments

If you want to name names on