Blu-ray: Radio On | reviews, news & interviews

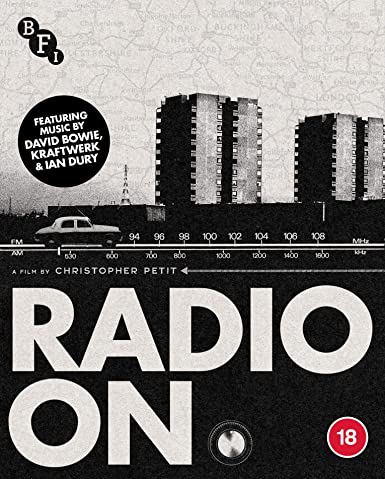

Blu-ray: Radio On

Blu-ray: Radio On

British cinema's finest road movie is anti-British cinema

Chris Petit's Radio On, his 1979 debut as writer-director, should be regarded as the first British psychogeography film.

Unfolding over a few wintry days centred on Saturday, 10 March 1979, Radio On is often painted as bleak, which is not quite accurate. B may end up as lonely and alienated at the end as he is at the beginning, when his live-in girlfriend (sullenly played by Sue-Jones Davies, a future mayor of Aberstywyth) leaves him, but there are grains of hope in some of the human connections he makes in transit. His offhand chat with a Wiltshire petrol pump attendant (pre-fame Sting) and singer who's obsessed with Eddie Cochran – killed in a car crash nearby in 1960 – is conducted in the language of rockabilly lovers and isn't, therefore, meaningless, even though the wannabe star pointedly remarks they won't meet again.

B's temporary friendship with a German woman (Lisa Kreuzer), whom he helps on her quest to recover her young daughter from her estranged husband, isn't pointless either because meeting her, a fellow traveller in loss and sorrow, elicits his compassion. Her apparent disappointment that they didn't sleep together the evening they met is mitigated by the smiles she gives B as she drives him back to his brother's flat after a visit to see her antagonistic émigré aunt in Weston-super-Mare. The brother's girlfriend (Sandy Ratcliff), whose angry, can't-be-bothered tone suggests she's in denial, is kinder to B at the end of their acquaintance than she had been when he arrived. People being unreliable, B can, in any case, succour himself with the pocketful of Kraftwerk cassettes his brother sent him before dying.

Included on this BFI release are fresh interviews with Petit and producer Keith Griffiths and a lively, informative spiel on the film by critic-author Jason Wood, a road movie specialist and Radio On fanatic. Wood explains how Petit's discovery of Kraftwerk engendered the film as a music-driven piece that prioritised driving, architecture (Ballardian high-rises, the Westway flyover), weather, and late '70s English dystopianism – relayed through radio news bulletins about Northern Ireland and a police sweep of a West Country porn ring Robert's brother may have belonged to – over character and story. Nonetheless, the performances of Beames, Ratcliff and Kreuzer are charged with suppressed emotion, the long-held shots of B cogitating his brother's demise and his own existential void being especially effective.

Included on this BFI release are fresh interviews with Petit and producer Keith Griffiths and a lively, informative spiel on the film by critic-author Jason Wood, a road movie specialist and Radio On fanatic. Wood explains how Petit's discovery of Kraftwerk engendered the film as a music-driven piece that prioritised driving, architecture (Ballardian high-rises, the Westway flyover), weather, and late '70s English dystopianism – relayed through radio news bulletins about Northern Ireland and a police sweep of a West Country porn ring Robert's brother may have belonged to – over character and story. Nonetheless, the performances of Beames, Ratcliff and Kreuzer are charged with suppressed emotion, the long-held shots of B cogitating his brother's demise and his own existential void being especially effective.

In contrast, Andrew Byatt played the Glaswegian Army deserter given a ride by B as a lit fuse. His bitter tale of ejection from school at 15, unemployment, soliciting, theft, and PTSD-inducing experiences on his tours in Belfast is a paradigm of the government's betrayal of young men.

A former Army brat in Germany and Time Out's film editor when he wrote the screenplay, Petit was influenced by Antonioni, Two-Lane Blacktop, Get Carter, Perfomance, and the desire to make a film that would be nothing like Mike Leigh's Abigail's Party – or anything traditionally British. He adopted the style of New German Cinema, specifically Alice in the Cities and Kings of the Road, the black-and-white entries in Wim Wenders's masterful Road Trilogy.

Wenders boarded Radio On as an associate producer and co-financier, asked Petit to write a part for Kreuzer (then Wenders's wife, who channelled her Alice in the Cities character), and loaned him his sound man Martin Müller and cameraman Martin Schäfer, assistant to Wenders's cinematographer Robby Müller. Radio On's beauty and Wenders-like ennui, illustrative of sociopolitical and spiritual malaise, owes greatly to the two Martins, who also insisted Petit film Sting performing Cochran's "Three Steps to Heaven"; intending to omit the scene, an affecting homage, Petit mercifully retained it. As well as Kraftwerk (whose "Uranium" fizzes demonically at ominous moments), the searing diegetic soundtrack's contributors include David Bowie (the Anglo-German version of "Heroes"/"Helden" used as a harbinger of tragedy), Robert Fripp, and the Stiff label's Wreckless Eric, Lene Lovich, Ian Dury, and the Rumour.

Radio On set a course for radical, advanced British road movies no one bothered to follow (or knew how to). Only Andrew Kötting's Gallivant – less concerned with the road than destinations and beloved family members – is a comparable English travel film. (Richard Eyre's The Ploughman's Lunch, written by Ian McEwen, is an excellent if stylistically conventional anti-Thatcher road movie.) The miracle of Radio On is its timelessness. No less now than in 1979, it makes you "feel in touch with the modern world," to cite the Jonathan Richman song "Roadrunner", from which Petit plucked his title. Trouble is, modern life is rubbish.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

Add comment