Best of 2022: Visual Arts | reviews, news & interviews

Best of 2022: Visual Arts

Best of 2022: Visual Arts

Museums and galleries are no longer afraid of giving women major shows

Have you noticed how exhibitions now seem to go on for ever and ever? Three months seems to be the norm, but five months is not unknown. Ever wondered why? In terms of time and money, mounting a major exhibition is incredibly expensive, of course.

And as Covid had such a disastrous impact on the finances of museums and public galleries, post-lockdown they’ve had to find ways of maximising revenue, and extending the duration of each show seems to be a popular solution. Inevitably, this reduces the number of exhibitions put on – so much so that I’d say a full-time critic would be hard pressed to find enough shows to review. It also appears to have upped the ante in terms of scale and ambition; every show, it seems, now aims to be a blockbuster!

The good news is that museums and galleries are no longer afraid of giving women major shows. With one exception, for me the most memorable exhibitions of the year have all been of work by women artists. The Hayward Gallery’s survey of sculptures and installations by Louise Bourgeois got things off to a memorable start. Bourgeois died in 2010 aged 98. During the last 20 years of her life, she used her own and her mother’s old clothes to create theatrical tableaux that revisit painful childhood memories of a sick mother and philandering father (main picture: Cell XXV (The View of the World of the Jealous Wife), 2001).

Her art is far more than a response to a fraught childhood, though. Having married, moved from Choisy-le-Roi (outside Paris) to New York and had children of her own, she was able to address the paradoxes, absurdities, joys and humiliations of being a woman in some of the most memorable sculptures of the 20th and 21st centuries. She was brilliant at creating physical equivalents of emotional states. Like a theatre of the mind, her tableaux encompass the humour, love, cruelty, compassion and despair that people are capable of. Having opened in May, Cornelia Parker’s Tate Britain retrospective continued until October. Early installations, such as Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View 1991 (pictured above) proved to be as dramatic as ever. Fascinated by the idea that destructive impulses can be harnessed for creative ends, with the help of the Army and some Semtex, she famously blew up a shed and its contents, then collected the debris and hung each item from a thread. Framed by the splintered remains of the wooden shell, the accumulated clobber of daily life hangs in the air as if caught mid-explosion. The initial thrill of the piece came from the spectacle of this frozen-in-time act of demolition. Now, though, the work has accrued further meaning; it feels like an ironic comment on a way of life that encourages endless accumulation and the waste of precious resources. Seeing all this stuff blown sky high felt incredibly liberating.

Having opened in May, Cornelia Parker’s Tate Britain retrospective continued until October. Early installations, such as Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View 1991 (pictured above) proved to be as dramatic as ever. Fascinated by the idea that destructive impulses can be harnessed for creative ends, with the help of the Army and some Semtex, she famously blew up a shed and its contents, then collected the debris and hung each item from a thread. Framed by the splintered remains of the wooden shell, the accumulated clobber of daily life hangs in the air as if caught mid-explosion. The initial thrill of the piece came from the spectacle of this frozen-in-time act of demolition. Now, though, the work has accrued further meaning; it feels like an ironic comment on a way of life that encourages endless accumulation and the waste of precious resources. Seeing all this stuff blown sky high felt incredibly liberating.

Like so many women, Vivian Maier was completely overlooked during her lifetime. She worked as a nanny but spent her spare time wandering the streets of New York and Chicago taking photographs. Over 40 years she took 140,000 pictures that were saved for posterity by sheer fluke when they were bought at auction by John Maloof who realised their extraordinary quality. He began publishing the pictures on Flickr and, in 2011, organised the first of many exhibitions which brought her international recognition.

Like so many women, Vivian Maier was completely overlooked during her lifetime. She worked as a nanny but spent her spare time wandering the streets of New York and Chicago taking photographs. Over 40 years she took 140,000 pictures that were saved for posterity by sheer fluke when they were bought at auction by John Maloof who realised their extraordinary quality. He began publishing the pictures on Flickr and, in 2011, organised the first of many exhibitions which brought her international recognition.

The MK Gallery’s retrospective, the first exhibition of her work in the UK, revealed what a sharp eye Maier had for the absurd encounter, the witty juxtaposition or the surreal moment – like the man with no ear making a phone call, or the burnt-out chair smouldering beside a waste bin on a New York street (pictured above right). American artist, Carolee Schneeman was also overlooked during her lifetime. While Claes Oldenburg and Robert Rauschenberg, with whom she had performed, were lorded and applauded, she was consistently ignored – until, that is, she was awarded a Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the Venice Biennale in 2017, just two years before she died.

American artist, Carolee Schneeman was also overlooked during her lifetime. While Claes Oldenburg and Robert Rauschenberg, with whom she had performed, were lorded and applauded, she was consistently ignored – until, that is, she was awarded a Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the Venice Biennale in 2017, just two years before she died.

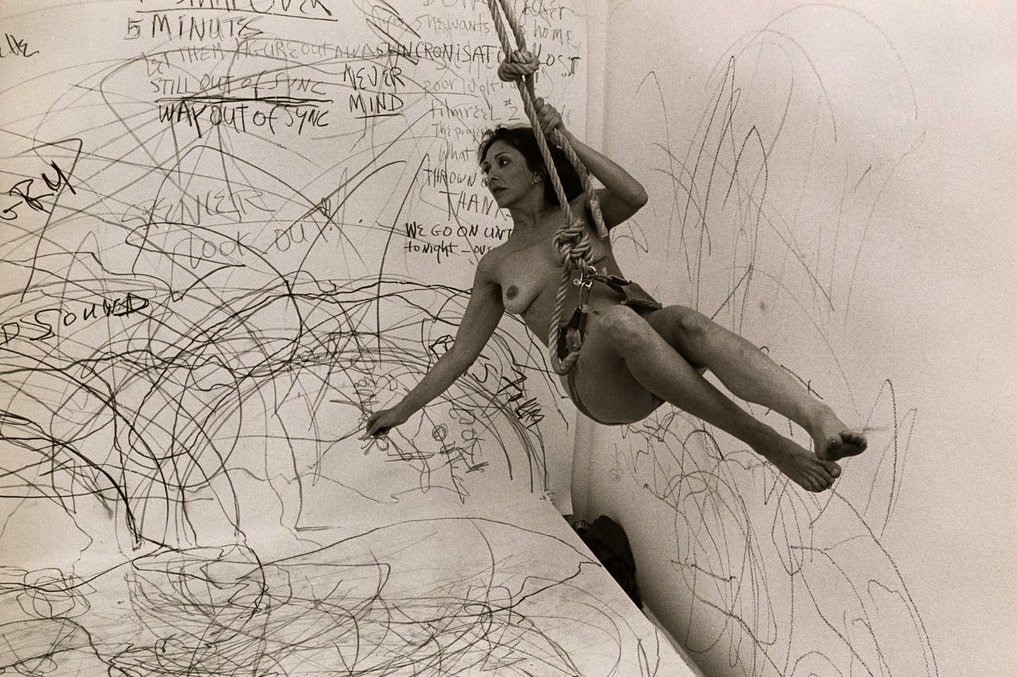

The Barbican’s retrospective brought home just how challenging were visceral performances such as Up to and Including Her Limits, 1976 (pictured above). Hanging naked from a harness, she swung back and forth, drawing and writing on the sheets of paper surrounding her. Physically and emotionally taxing, it explored the limits of her endurance as well as the legal limits of appearing naked in public. Her challenging and deliberately messy contribution to post-war American art has at last been recognised and her place in history acknowledged. Magdalena Abakanowicz’s huge woven sculptures are still on show at Tate Modern until May 21 2023. Hanging from the ceiling, ten magnificent forms create a forest of darkly intriguing presences. Made from rope, sisal and horsehair dyed black or rich brown, they are reminiscent of hollowed-out tree trunks, gargantuan cloaks or underwater creatures such as giant stingrays.

Magdalena Abakanowicz’s huge woven sculptures are still on show at Tate Modern until May 21 2023. Hanging from the ceiling, ten magnificent forms create a forest of darkly intriguing presences. Made from rope, sisal and horsehair dyed black or rich brown, they are reminiscent of hollowed-out tree trunks, gargantuan cloaks or underwater creatures such as giant stingrays.

Next she began dying the material gorgeous colours and suspending the hangings in more open configurations (pictured above: detail of installation shot by Madeline Buddo) that makes them extremely seductive and their fleshy folds suggestive of human bodies and other living organisms. Opened out like a double cape, for instance, Abakan January-February 1972 resembles a pair of giant lungs joined by a tangled array of bronchial tubes.

The exception to my all-female list is Lucian Freud; you can still catch his National Gallery retrospective (until Jan 22 2023). I’ve always found his paintings cruelly dispassionate; the God’s-eye view he adopted – looking down on his sitters – and the eagle-eyed scrutiny to which he subjected them seems arrogant and merciless. But hung in these spacious rooms, the paintings reveal their visceral power. When you have the space to stand back, canvases that close-to often seem clogged and inert, miraculously cohere into three-dimensional depictions.

The exception to my all-female list is Lucian Freud; you can still catch his National Gallery retrospective (until Jan 22 2023). I’ve always found his paintings cruelly dispassionate; the God’s-eye view he adopted – looking down on his sitters – and the eagle-eyed scrutiny to which he subjected them seems arrogant and merciless. But hung in these spacious rooms, the paintings reveal their visceral power. When you have the space to stand back, canvases that close-to often seem clogged and inert, miraculously cohere into three-dimensional depictions.

Freud spent 70 years relentlessly examining his own and his sitter’s faces and bodies and recording what he saw in paint (pictured left: Sleeping by the Lion Carpet, 1996) and these studio encounters are full of tension. There’s a power struggle going on; it’s as if Freud wants you to question who has the right to look at whom. His paintings are like an assault on both eye and mind; I left feeling as if I’d been punched in the gut.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment