Life is messy and so is Carolee Schneeman’s work. She wanted it that way. Breaking down the barriers between art and life, between inhabiting a woman’s body and using it as primal material, was a key objective.

And if this meant appearing naked in performances or filming herself having sex, so be it. “Can I be an image and an image-maker?” was a question she sought to answer over and over again in her work. And in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, the male-dominated art world of New York responded with a vehement “No!”.

In 1954, for instance, she was kicked off the undergraduate course at Bard College in upstate New York for “moral turpitude”, because she dared to make a painting of herself in the nude! The hypocrisy is breathtaking; when a man paints a female nude that’s tradition, but when a woman portrays herself naked it’s indecent, a challenge too far. Challenging the status quo, which she referred to as the “Art Stud Club”, was one of her missions and, in doing so, she produced some seminal works. Her response to Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings, for instance, was Up to and Including Her Limits, 1976 (main picture). Hanging naked from a harness, she swung back and forth in a trance-like state, drawing and writing on the sheets of paper surrounding her. Physically and emotionally taxing, the performance explored the limits of her endurance as well as the legal limits of appearing naked in public.

Challenging the status quo, which she referred to as the “Art Stud Club”, was one of her missions and, in doing so, she produced some seminal works. Her response to Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings, for instance, was Up to and Including Her Limits, 1976 (main picture). Hanging naked from a harness, she swung back and forth in a trance-like state, drawing and writing on the sheets of paper surrounding her. Physically and emotionally taxing, the performance explored the limits of her endurance as well as the legal limits of appearing naked in public.

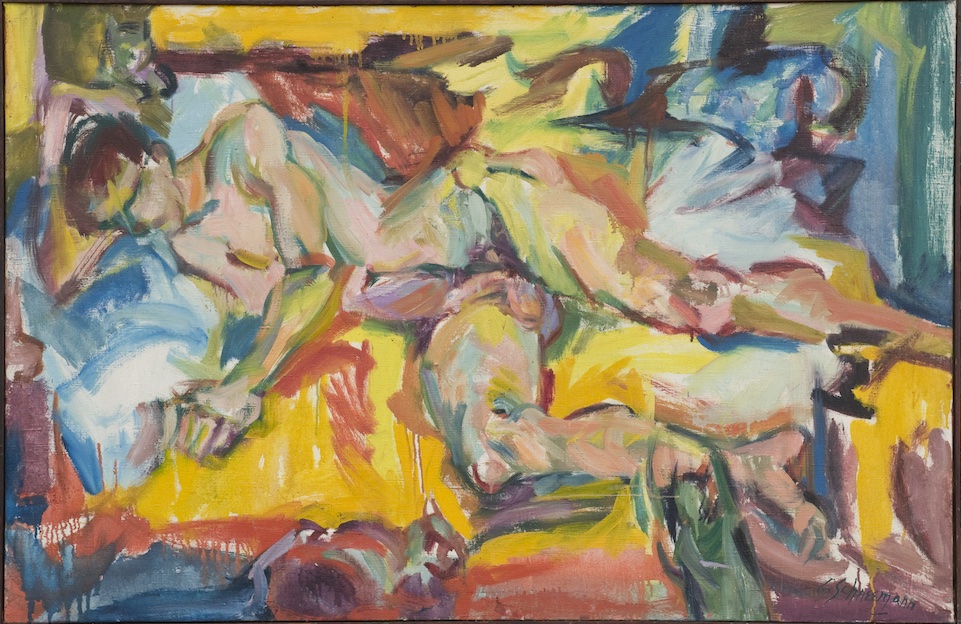

She was also exploring the limits of painting. Although most of her work is in other media – film, video, photography, installation and performance – Schneeman always described herself as a painter who “treat(s) space as if it’s time.” And the flickering, dynamic brushwork of early paintings like Personae: JT and Three Kitchs, 1957 (pictured above) creates a restless energy, as if the model is about to jump up and go walkabout.

She liked working to music and, wanting to incorporate sound, she attached an unwound spool of tape to the frame of One Window Is Clear – Note to Lou Andreas-Salomé, 1969. On the tape is a message to the Russian-born psychoanalyst named in the title, but the tangled recording dangles silent and useless, an emblem of frustration.

Then she expanded into 3D first with assemblages and then boxes inspired by Joseph Cornell; but whereas his collections are like miniature museums housing precious objects, her boxes contain splintered glass and the charred remains of items she has set on fire. Next she began staging solo performances for the camera; daubing her naked body in paint, she interacted with her assemblages to become a live element in the installation. This was a turning point, but it was only when she began collaborating with dancers – using her own and other people’s bodies actually to move through space and time – that she found her metier.

Then she expanded into 3D first with assemblages and then boxes inspired by Joseph Cornell; but whereas his collections are like miniature museums housing precious objects, her boxes contain splintered glass and the charred remains of items she has set on fire. Next she began staging solo performances for the camera; daubing her naked body in paint, she interacted with her assemblages to become a live element in the installation. This was a turning point, but it was only when she began collaborating with dancers – using her own and other people’s bodies actually to move through space and time – that she found her metier.

She was a founder member of the Judson Dance Theater; from 1962 in a basement in Greenwich Village key figures like Deborah Hay and Yvonne Rainer staged groundbreaking performances that reconfigured the parameters of contemporary dance. Schneeman invited the messiness of life into pieces that were carefully structured yet appeared chaotic. Dancers responded to scores including instructions like “run in 1 of 4 ways: forwards, backwards, in a low crawl and spinning with potential to fall”.

Their reception was rarely positive. Jill Johnston, dance critic of the Village Voice, described Chromolodeon, 1963 as “a brainless, messy 'happening'”. She wasn’t far off the mark, since Schneeman deliberately courted failure by embracing spontaneity. “I want a dance,” she wrote, “where dancers can fall, can crash into a wall… can crash into each other… where dancers can fart, stop and start… can leave the performance… and return, or not return.” Ironically, scores like these have since become classics, used to teach dance students how to improvise.

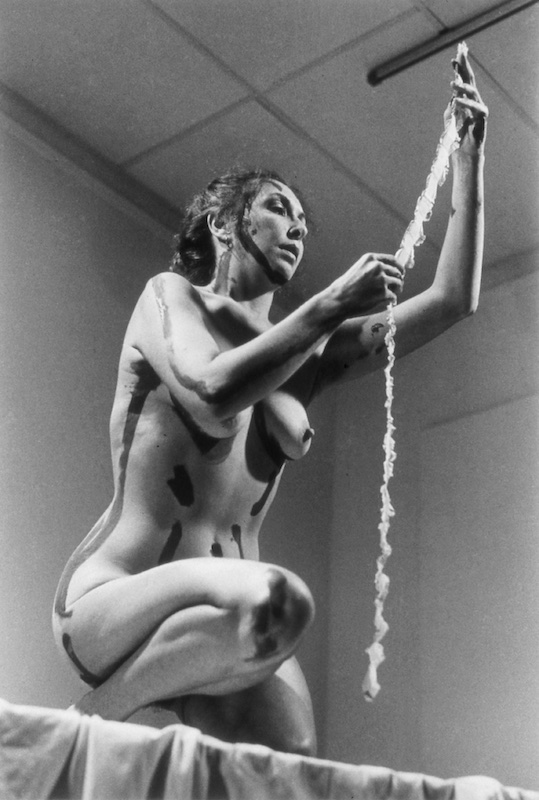

Although shocking at the time, performances like Meat Joy (pictured below) have not aged well. A group of men and women clad in fur bikinis roll orgiastically around in puddles of paint among chickens carcasses, phallic vegetables and dead fish. When it was first performed in Paris in 1964, a member of the audience was so outraged he tried to strangle the artist. It was restaged at the Whitechapel Gallery in 2002, by which time the sexuality seemed almost innocent but the inclusion of dead animals was really problematic. On the other hand, Interior Scroll, 1975 (pictured above middle) has retained its relevance and visceral power. Standing stark naked, the artist pulls out a long strip of paper from her vagina and reads a message addressed to male critics of her films. “There are certain films we cannot look at,” she reads. There follows a list of the many attributes she values and they decry: “The personal clutter, The persistence of feeling, The hand-touch of sensibility, The diaristic indulgence, The painterly mess, The dense gestalt, The primitive techniques.” She concludes that: “I saw my feelings were worthy of dismissal. I’d be buried alive, my works lost.”

On the other hand, Interior Scroll, 1975 (pictured above middle) has retained its relevance and visceral power. Standing stark naked, the artist pulls out a long strip of paper from her vagina and reads a message addressed to male critics of her films. “There are certain films we cannot look at,” she reads. There follows a list of the many attributes she values and they decry: “The personal clutter, The persistence of feeling, The hand-touch of sensibility, The diaristic indulgence, The painterly mess, The dense gestalt, The primitive techniques.” She concludes that: “I saw my feelings were worthy of dismissal. I’d be buried alive, my works lost.”

She was absolutely right. While artists like Claes Oldenburg and Robert Rauschenberg, with whom she had performed, were written about and lorded and applauded, she was consistently overlooked – until 2017, that is, when at the Venice Biennale she was awarded a Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement. Just two years before she died, her challenging and deliberately messy contribution to postwar American art was finally recognised and her place in history acknowledged.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment