Shostakovich: Symphonies 8, 9 and 10 Berliner Philharmoniker/Kirill Petrenko (Berlin Phil Media)

Shostakovich: Symphonies 8, 9 and 10 Berliner Philharmoniker/Kirill Petrenko (Berlin Phil Media)

Potential purchasers worrying that the Berlin sound might be a little too well-upholstered for Shostakovich needn’t worry; one striking aspect of the performances captured in this set is their rawness and bite. Herbert von Karajan made two superb recordings of Symphony No. 10 with the Berlin Philharmonic in the 1960s and 1980s, and Kirill Petrenko’s new one is similarly involving. That he’s got an orchestra capable of playing the second and fourth movements up to tempo is a plus: I’ve rarely heard the demonic scherzo dispatched with such precision. Do watch the bonus Blu-ray disc and marvel at the woodwind section’s collective articulation. Key instrumental solos, like the solo horn in the third movement and the frenzied clarinet line as the finale picks itself up for the final sprint are superbly done. Petrenko’s first movement is broad (why do so few conductors follow Shostakovich’s moderato marking?) but gripping, the piccolos’ lament in the final bars supported by just a hint of warmth in the strings. The symphony’s coda is a toe-tapping triumph here, Petrenko describing it in the booklet as “the greatest stroke of liberation in Shostakovich’s artistic output.” Recorded in October 2021, the video shows a full audience in the Philharmonie, whereas the two earlier symphonies were taped a year before, the listeners in the 9th socially distanced.

This reading of Symphony No. 9 is a treat. Watch the video for Petrenko’s smile before beginning Shostakovich’s “Allegro”, and for the lower strings grinning as the third movement opens. Trumpets and bassoons acquit themselves brilliantly, the bassoon’s long soliloquy deeply eloquent. You might prefer a bit more vulgarity and bombast at the close, but this is a wonderfully witty and entertaining reading. Petrenko’s 8th Symphony marries emotional oomph and spectacle. Lower strings have visceral impact in the bare opening statement, and the brass don’t flinch in the movement’s development. There’s a terrific trumpet solo in the central “Allegro non troppo”, and the tam tam crash at the start of the passacaglia will have your windows rattling. The finale’s equivocal coda is deeply moving. Audiophiles will appreciate the production values; this is the best-sounding recording I’ve yet heard from this source. Highly recommended.

Stravinsky The Soldier’s Tale Hallé/Sir Mark Elder (Hallé)

Stravinsky The Soldier’s Tale Hallé/Sir Mark Elder (Hallé)

Stravinsky’s The Soldier’s Tale was written during WWI, when he was living in Switzerland, as a deliberately pared-down theatre piece: minimal set, three actors, seven musicians. It tells the folk-tale of a soldier who sells his violin to the devil, with a text by C.F. Ramuz. It has always been better known in the suite Stravinsky made of the instrumental movements, and I’ve always found performances of the whole thing, with narration and action, to be overextended, the opposite of the succinctness that is Stravinsky’s hallmark.

This new translation by Jeremy Sams (who did such brilliant work translating Winterreise into English as Winter Journey) does add a brio and fresh punch, and is well delivered by Richard Katz (Narrator), channelling Brian Cant from vintage BBC children's series Playaway, Martins Imhangbe as a likeable Soldier and Mark Lockyer, a perky, rustic Devil. But there remains an imbalance that is unbridgeable: there are about 33 minutes of music in a 58-minute running time (and a lot of those come together in the brilliant dance sequence at the end), so there are long stretches of speech between the musical episodes. The playing of the small band taken from the Hallé is great, from Peter Lang’s gutsy violin to Emily Hultmark’s quizzical bassoon, and it’s all led briskly by Sir Mark Elder. There are lots of recordings of The Soldier’s Tale, with quite the range of speakers: Jeremy Irons, Harrison Birtwistle, Peter Ustinov, Christopher Lee, Roger Waters(!) – the list goes on, and this Hallé version is better than most. But I would always probably go for the suite, all killer no filler, for which I would recommend Pierre Boulez with members of the Cleveland Orchestra on Deutsche Grammophon. Bernard Hughes

Vaughan Williams Live Vol. 4 (Somm)

Vaughan Williams Live Vol. 4 (Somm)

This is a disc to treasure, opening with a Carnegie Hall performance of Vaughan Williams’ Tallis Fantasia which really defies its age. The strings of the New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra under Dimitri Mitroupolos produce a warm, vibrant sound that’s intoxicating, Mitropoulos audibly smitten by the work. That the playing is so rich surely owes something to the orchestra’s recently departed Music Director, who’d recently left the city to take up a new post in Manchester. More on him later. Presumably this is an off-air recording (no details are given other than dates), and Lani Spahr’s remastering is excellent. Mitropoulos also conducts a 1952 account of Vaughan Williams’ quirky, neglected Concerto for Two Pianos and Orchestra, a reworking of an earlier single-player concerto. It’s an enjoyable if uneven piece, and the recorded balance works against it here, the busy piano lines often buried in the thickly scored outer movements. Soloists Arthur Whittemore and Jack Lowe get more room to breathe in the gorgeous central “Romanza”, and in the concerto’s soft epilogue.

Finally, there’s the 8th Symphony, dedicated to Sir John Barbirolli and the Hallé Orchestra. They gave the premier in 1956 and their early stereo recording still sounds vivid. This 1964 Free Trade Hall performance is less well-recorded, but the playing has more panache. The “Scherzo alla marcia” is a spiky, witty delight (listen out for the trumpet solo 39” in!), and the strings have plenty of bloom in the radiant “Cavatina”. If you’re not grinning as the last movement clatters to its conclusion, you’ve no soul. And it’s nice that Spahr has left in the voice of a 1964 Radio 3 continuity announcer after the final unison D’s have died away, though his fruity tones might make you jump. An excellent compilation. More, please.

Magnificat 3 The Choir of St John’s College, Cambridge/Andrew Nethsingha (Signum)

Magnificat 3 The Choir of St John’s College, Cambridge/Andrew Nethsingha (Signum)

After 15 years as Director of Music of St John’s College, Cambridge, Andrew Nethsingha arrived at Westminster Abbey in January, just in time to take centre stage at the Coronation. This has thrust him into the attention of many casual viewers, with lots of praise for his masterful musical stewardship of a major national event. In the last few years at St John’s, the choir recorded a number of albums of liturgical repertoire for Signum (the Vaughan Williams Mass of 2018 is a favourite) and this is the third of a series of Mag-and-Nuncs – with one last one promised.

Where the second leant more into recent and living composers – including Giles Swayne, Arvo Pärt and Julian Anderson – this new instalment goes back to the mid-20th century Anglican mainstream of Howells, Leighton and Dyson. It is impeccably sung and played (by organist George Herbert) and is an accurate reflection of what goes on in Evensong every week in the big Oxbridge colleges and cathedrals. This is not a world I am steeped in, and is a very specific musical language of rich chordal writing for voices, and occasionally thunderous organ, but it shows what the top end of collegiate choirs sounds like. That said, it was the less typical pieces that bookend the album that stirred me most: a terrific opening Nunc Dimittis by the Russian composer Pavel Chesnokov (1877-1944), who I have never heard of, but whose Orthodox-flavoured piece is in the vein of his contemporary Rachmaninoff, with whom he shared a teacher. At the other end of the programme are the Canticles in C by Bryan Kelly (b.1934) from 1965 (commissioned for the same festival as Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms). Another composer I didn’t know, a student of Nadia Boulanger, his setting borrows from Latin rhythms, and dances with a joyous energy not always found in liturgical music. Bernard Hughes

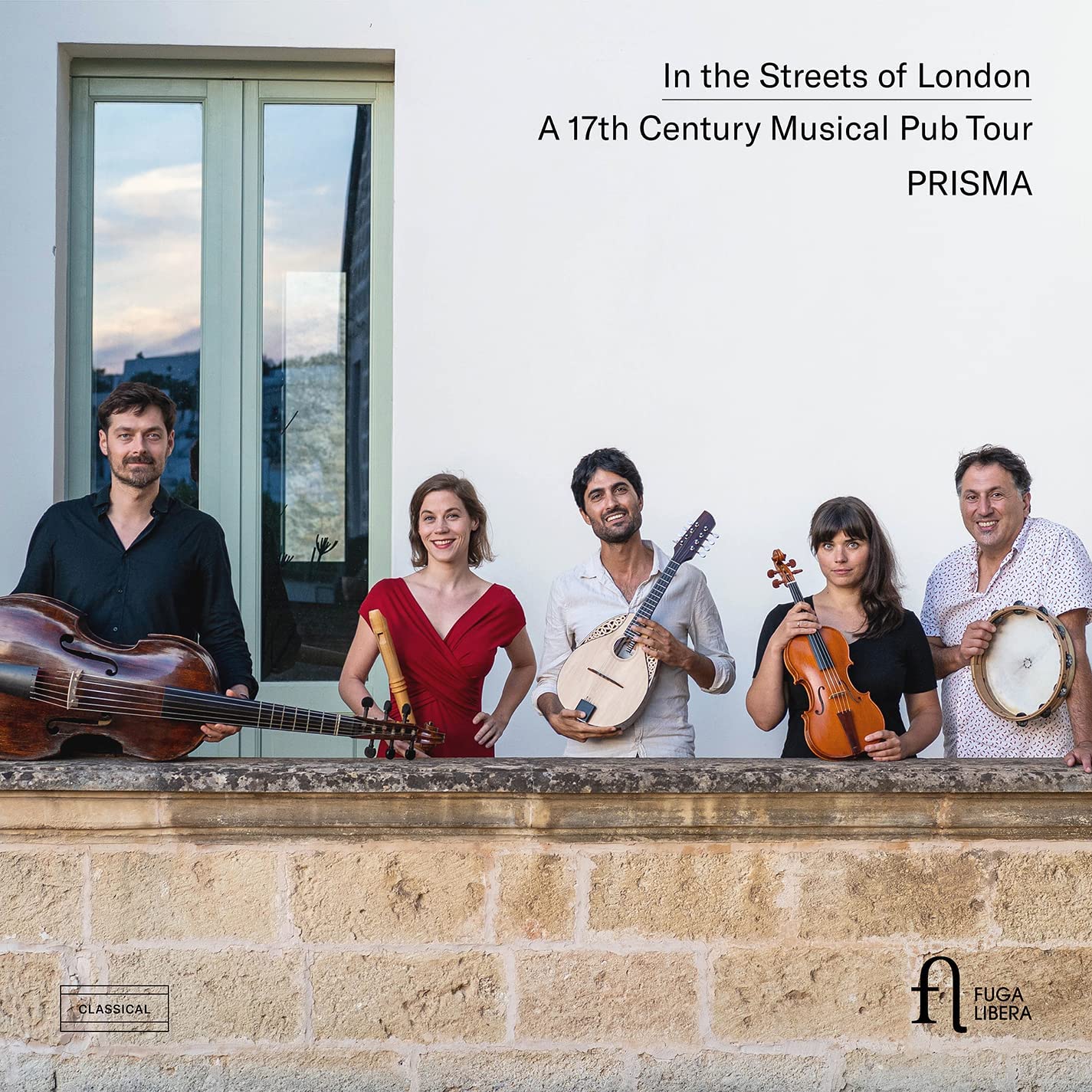

In the Streets of London: A 17th Century Musical Pub Tour Prisma (Fuga libera)

In the Streets of London: A 17th Century Musical Pub Tour Prisma (Fuga libera)

This disc opens with some atmospheric whistling. Hmm, what's that tune? Surely it can’t be…? Part of me wishes that the virtuosic quartet Prisma had then inserted an orotund voiceover quoting from the sleeve note: “London 1651: the Civil War enters its third year. Opera houses and theatres have long been closed, but below the surface, the nightlife simmers…” We’re asked to imagine that we’re in a pub with Henry Purcell, publisher John Playford and violinist Niel Gow, listening to a generous selection of popular ditties. Numbers taken from Playford’s The Dancing Master rub shoulders with popular tunes by Purcell and a selection of Irish and Scottish folk tunes. This is a delightful album, the tunes played, variously, on recorder, violin, mandolin and viol, Murat Coşkun adding judicious touches of percussion. Try the little “Curtain Tune” from Purcell’s Timon of Athens, or the second track’s folksong medley, including such vintage gems as “Trip it Upstairs” and “My Wife is a Wanton Wee Thing”. The group’s idiomatic vocals add colour to “The Star of County Down”. Thomas Forde’s tiny “Cate of Bardie” fizzes.

There’s not a dud track here. A clever take on Ralph McTell’s “Streets of London” caught me unawares (despite the album's title) but had me giggling, and violist Soma Salat-Zakarias’s bass lines in the “Groud After the Scottish Humour” are punchy and sonorous. A sequence of five traditional Irish tunes brings the disc to an uproarious and uplifting conclusion, followed by some more whistling. This is a terrific collection, funny, moving and exciting by turns, a shoo-in for my end-of-year ‘Best of 2023’ list, and something to file alongside your Alehouse Sessions CDs. Trust me – it’s that good.

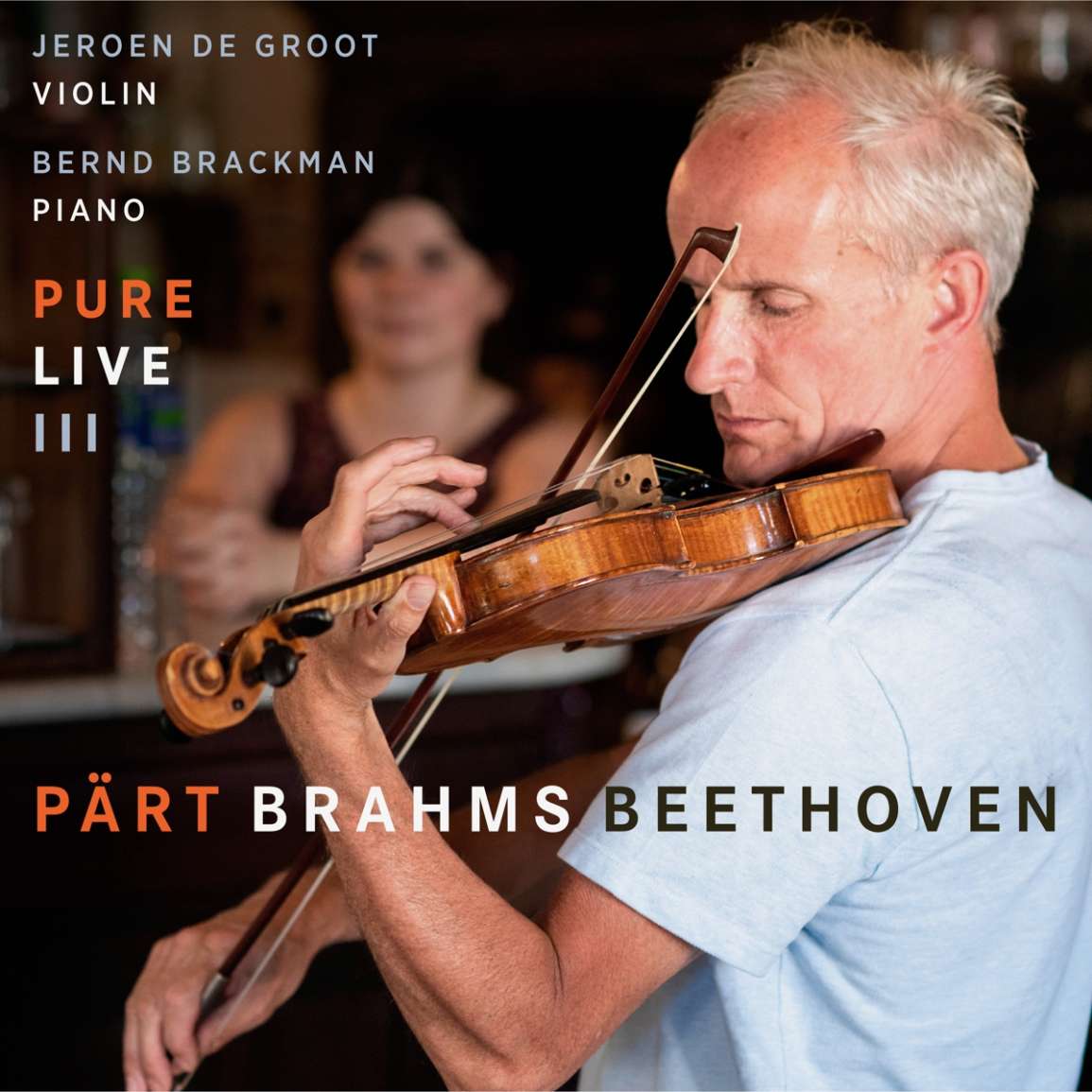

Pure Live iii: Music by Pärt, Brahms and Beethoven Jeroen de Groot (violin), Bernd Brackman (piano) (Zefir Records)

Pure Live iii: Music by Pärt, Brahms and Beethoven Jeroen de Groot (violin), Bernd Brackman (piano) (Zefir Records)

Beginning a live recital with Arvo Pärt’s Fratres is a little mischievous, violinist Jeroen de Groot’s reading full of poise and cool beauty. He and pianist Bernd Brackman do really ratchet up the tension midway through, the playing scarily intense, but the cooling off is mesmeric. Pärt’s spareness makes Brahms’s Sonata No. 3 all the more powerful, a piece which starts similarly quietly but hints at its scope and size before a minute has elapsed. De Groot and Bernd are alert to the music’s warmth as well as its weight; the first movement’s second subject is sweetly phrased, and de Groot’s hushed playing at the start of the “Adagio” is perfectly pitched. Bernd’s soft flurries of notes at the start of the scherzo are immaculate, and the passage in the finale where the music seems to dissolve into space is heart-stopping.

Beethoven’s Kreutzer Sonata makes for an epic second half. De Groot and Brackman’s slow introduction lulls us into a false sense of calm, before the first movement’s glowering “Presto” erupts into life. The coda is desolate, making the central movement’s serene sequence of variations both disconcerting and welcoming. Stops are duly pulled out in the closing tarantella, de Groot and Brackman brilliantly coordinated, relishing every twist and turn before an exultant finish where it’s difficult not to join in with the audience applause. Taped in November 2021 in the Zeeuwse Concertzaal in the south-western Netherlands, the recorded sound has bloom and immediacy.

Add comment