A traditional Korean house has appeared at Tate Modern. And with its neat brickwork, beautifully carved roof beams and lattice work screens, this charming dwelling looks decidedly out of place, and somewhat ghostly. Go closer and you realise that, improbably, the full-sized building is made of paper. It’s the work of South Korean artist Do Ho Suh (main picture).

In 2013, he covered his childhood home in mulberry paper and painstakingly made a rubbing of every single nook and cranny of the exterior. He left the paper in situ for nine months until the drawing had weathered to resemble an old sepia photograph – faded and water damaged. It’s as though he were trying to fix a memory that had begun to dissolve during the 20 odd years since he left home.

When his parents built the house in Seoul, in 1972, it was already an anomaly. Traditional homes like this hanok were being torn down to make way for modern apartment blocks. Suh’s life-sized replica is a memorial, then, both to his childhood home and the collective loss of these beautiful buildings.

Hanoks were constructed so they could be taken apart and moved to another location and the process, referred to as “walk the house”, gives Suh’s exhibition its title. A series of delightful sketches, made with coloured threads embedded in paper, show little houses (detail pictured right) marching by as smoke rings puff merrily from their chimneys. And in drawings reminiscent of Louis Bourgeois’ depiction of herself as a house, Suh merges his body with a dwelling as if in realisation of the wish “to carry my home, my house, with me at all times like a snail.”

Hanoks were constructed so they could be taken apart and moved to another location and the process, referred to as “walk the house”, gives Suh’s exhibition its title. A series of delightful sketches, made with coloured threads embedded in paper, show little houses (detail pictured right) marching by as smoke rings puff merrily from their chimneys. And in drawings reminiscent of Louis Bourgeois’ depiction of herself as a house, Suh merges his body with a dwelling as if in realisation of the wish “to carry my home, my house, with me at all times like a snail.”

When he went to America in 1991 to study at Rhode Island School of design, he felt a profound sense of dislocation, even though his exile was voluntary. “Once you leave your first home”, he says, “a perpetual sense of displacement and vulnerability sets in, even within the solid walls that protect you physically.”

He had a recurring dream that, buoyed up by a parachute, his childhood home flew over the Pacific to join him. Ever since, the question of where and what constitutes home has been the subject of incredibly moving and beautiful work.

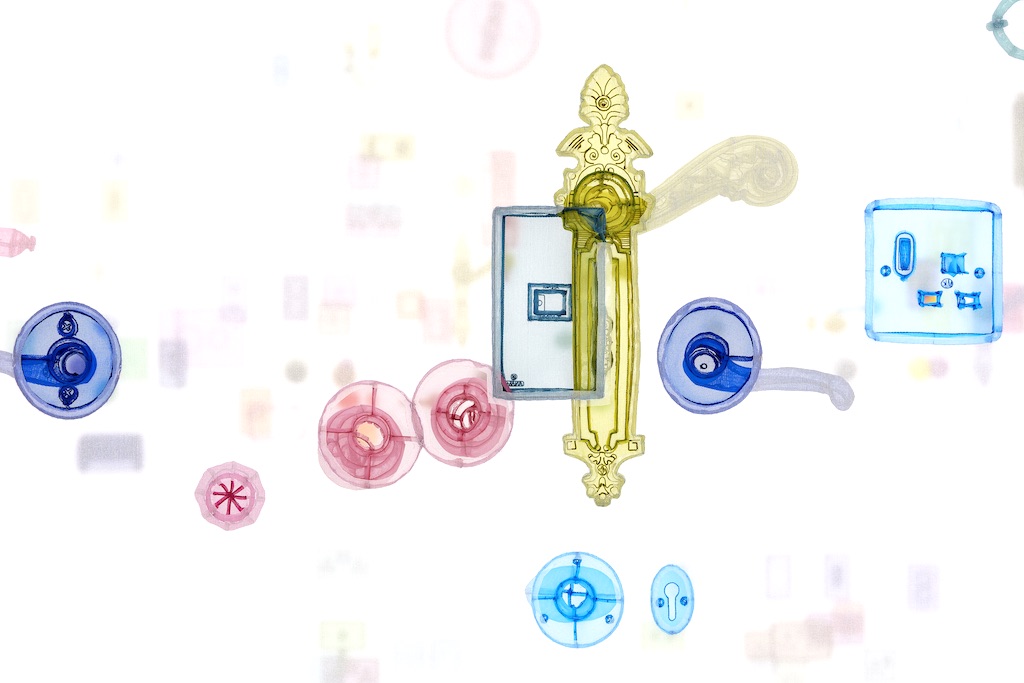

In 2014 he made rubbings of the fixtures and fittings in the New York apartment where he’d lived for nearly 20 years. Following the death of his landlord from dementia, the building was up for sale and Suh felt the need somehow to fix the memory of the dwelling they’d shared so that it would not slip away altogether. Assembled in groups, the paper knobs, handles, switches and wall lights that, for two decades, had been an integral part of his daily life are hung alongside a window, shutter and sections of wall, like an archival display of exotic artefacts – as though they were already becoming strangers. Memories can fade slowly or be wilfully suppressed. Hung on a nearby wall is a set of graphite panels so dark they resemble sheets of lead. These are rubbings of an empty building in Gwangju, a city where in May 1980 an uprising against the military dictatorship was brutally suppressed. Many protestors were killed, the city was laid to waste and all references to the event were removed from public record. Working blindfold in acknowledgement of this erasure, Suh and five helpers recorded the interior of a building that had once housed cinema employees. This sombre installation is, then, a memorial that makes visible a historic act of bravery.

Memories can fade slowly or be wilfully suppressed. Hung on a nearby wall is a set of graphite panels so dark they resemble sheets of lead. These are rubbings of an empty building in Gwangju, a city where in May 1980 an uprising against the military dictatorship was brutally suppressed. Many protestors were killed, the city was laid to waste and all references to the event were removed from public record. Working blindfold in acknowledgement of this erasure, Suh and five helpers recorded the interior of a building that had once housed cinema employees. This sombre installation is, then, a memorial that makes visible a historic act of bravery.

Suh now lives in London. He didn’t come here empty handed; along with his luggage he brought memories in tangible form. Since leaving Seoul, he has created full-sized replicas of every place he has called home. Made with translucent polyester fabric, these architectural skins have been linked together to form Nest/s 2024 (pictured above: detail) a colourful corridor that invites you to walk through time, as it were, following in the artist’s footsteps as he moves from place to place.

The white fabric walls of Perfect Home: London, Horsham, New York, Berlin, Providence, Seoul 2024 (pictured below: detail) enclose a space the size of his current flat. The walls are lined with replicas of fixtures and fittings – door knobs, handles, sockets, switches, lights, locks, thermostats and so on. They are joined by replicas of the same items from previous homes; familiar yet subtly different, each one is positioned where it was located in its original setting and coloured accordingly. Often overlapping and dotted all over the place, they accumulate like the notes of a symphony that celebrates the ongoing rituals of daily life and their continuation no matter where you find yourself.

While your memories may accompany you into the future, you are never able to return to the past, because you and the place you hold dear have both changed. The apartment blocks built in Seoul in the 1960s to replace the hanoks have now been torn down to make way for high rises and, in London, housing estates from the same era have similarly been demolished. In twin videos, Suh pays tribute to this constant state of flux and the dislocation that it causes.

While your memories may accompany you into the future, you are never able to return to the past, because you and the place you hold dear have both changed. The apartment blocks built in Seoul in the 1960s to replace the hanoks have now been torn down to make way for high rises and, in London, housing estates from the same era have similarly been demolished. In twin videos, Suh pays tribute to this constant state of flux and the dislocation that it causes.

He began filming Dong In, an estate in Daegu, South Korea in 2022, when it was already empty. The camera dwells on the desolation of the crumbling concrete blocks and the sad traces of lives spent in rooms now empty save for peeling wallpaper and tatty linoleum, a ragged curtain or a forgotten shirt trembling in the draft from a broken window.

When, in 2018, he began filming the demolition of Robin Hood Gardens in Poplar, East London, a few tenants were clinging on in melancholy isolation while, through the window, a bulldozer could be seen nibbling away at the neighbouring block. Mixing drone footage, flythroughs (that effortlessly seem to pass through walls) time-lapse photography and montages of stills, Suh creates incredibly beautiful sequences. Derelict units (pictured below: still, detail) and empty corridors are juxtaposed with the disorderly comfort of flats still crammed with furniture and personal belongings. Each frame resembles a perfectly crafted installation which, along with the silence, confers a ritualistic sense of dignity on the lives they record without a trace of sentimentality. And it makes the destruction seem the more shocking. It’s rare for an artist to change one’s perspective, but Do Ho Suh’s aesthetic is so exquisite and so precise that, on leaving his glorious exhibition, I saw the world as if through his eyes. I found myself noticing the particularities of every surface with unusual clarity and extreme pleasure. Thank you.

It’s rare for an artist to change one’s perspective, but Do Ho Suh’s aesthetic is so exquisite and so precise that, on leaving his glorious exhibition, I saw the world as if through his eyes. I found myself noticing the particularities of every surface with unusual clarity and extreme pleasure. Thank you.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment