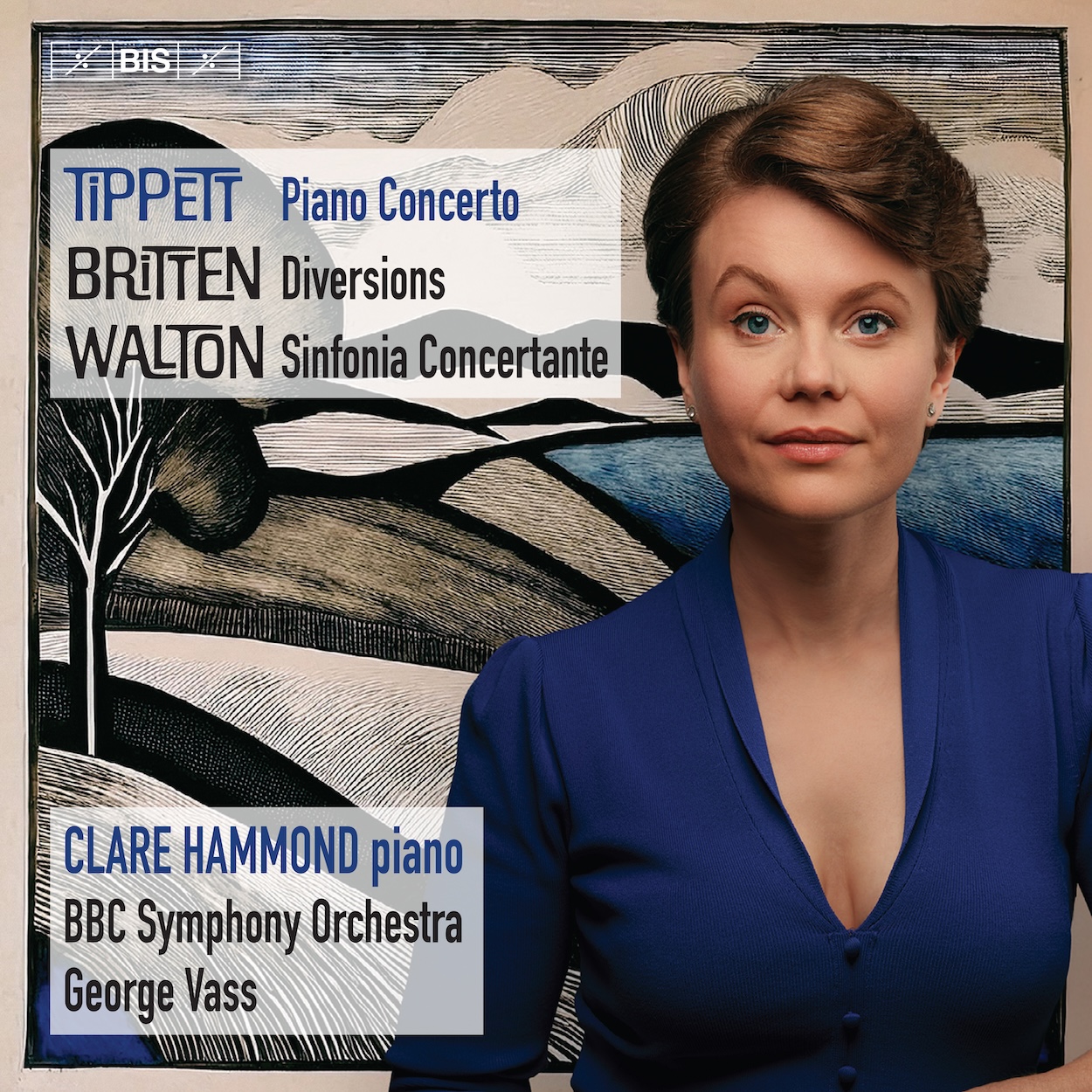

British Piano Concertos: Walton, Britten & Tippett Clare Hammond (piano), BBC Symphony Orchestra/George Vass (BIS Records)

British Piano Concertos: Walton, Britten & Tippett Clare Hammond (piano), BBC Symphony Orchestra/George Vass (BIS Records)

I really liked this programme of neglected British piano concertos by the always excellent pianist Clare Hammond, accompanied by conductor George Vass, himself committed to the cause of promoting British music over many years. Britten’s one-handed Diversions, written for Paul Wittgenstein, and Walton’s Sinfonia Concertante are both full of youthful vivacity, although both have troubled histories.

Best known by far is Michael Tippett’s Piano Concerto, a top-three in my Tippett favourites list, alongside the Fantasia on a Theme by Corelli and the Second String Quartet. I observed recently in this column how Tippett is one of the most uneven of composers, but when he’s on song I find him irresistible. The concerto is big-boned, with the heft of a large construction, and designed to explore the piano’s “poetic capabilities”, in which it really succeeds. Hammond paces her passages of build-up so the climaxes really hit and her playing brings out the melodic lines sometimes hidden in a barrage of notes. The orchestration is often quite dense (a bit of a Tippett weakness) but Vass keeps it light, the BBC Symphony Orchestra revelling in the sparser woodwind solos, but also finding a nobility in the brass fanfares. The second movement is labyrinthine and a touch self-important, although Hammond negotiates her way through its thickets with a clear eye. But it’s in the last movement that everything comes together: spirited pianism, orchestral sparkle and the dancing high spirits that characterised Tippett’s best music from the early 50s.

The Walton Sinfonia Concertante that opens the album has an interesting backstory. Written as a ballet score for Diaghilev in 1926, dismissively spurned by the great impresario. Reworked as a concert piece in 1928 and then into its final form in 1943, Walton was clear it was not a concerto, but a symphony “with piano obbligato”. To me it works as a concerto, with dialogue between piano and orchestra, and it has the vivacity and wit of Walton’s early style, with a serious and thoughtful second movement, as in the Tippett. As Hammond notes in her liner notes, Walton’s downplaying of the piano’s role makes this a somewhat unappealing prospect for pianists, but she does a great job of advocacy, her playing dynamic and, in the slow movement, inward to the right degree.

The other piece is Britten’s one-hand concerto Diversions, on which Hammond is an expert, having written her doctoral thesis about it. The chequered history here consists of the dedicatee Paul Wittgenstein making significant changes to Britten’s music in his performances, to the composer’s distress. The piece is a set of variations, each strongly characterised, the piano collaborating with the orchestra, rather than being in heroic combat. Hammond’s playing of this attractive work is perfectly judged and accompanied sympathetically by Vass and the BBCSO, with the “Nocturne” a particular highlight. Bernard Hughes

Terry Riley: The Columbia Recordings (Sony)

Terry Riley: The Columbia Recordings (Sony)

Released to celebrate pioneering minimalist Terry Riley’s 90th birthday, this handy box contains the four LPs of his music released by CBS between 1968 and 1980. The most famous, In C, sounds on paper as if it shouldn’t work, just a single sheet of A4 containing 53 pithy melodic phrases. Riley’s performance directions are both incredibly precise and alarmingly vague, the exact number of players required left open-ended, the most critical instruction being “it is very important that performers listen very carefully to one another and this means occasionally to drop out and listen”. Here, pianist Margaret Hassell heroically maintaining order by pounding out repeated high Cs on a piano for 42 minutes. Riley plays saxophone on this famous recording, the eleven-piece ensemble overdubbed to create a 28-voice performance. Producer David Behrman revisits the sessions in an entertaining booklet note, describing how a newly acquired eight-track tape recorder made the project possible. Each performance is unique, and this one, the ensemble dominated by woodwinds, has a pungent perkiness that’s uniquely uplifting, and listening to it on this beautifully remastered CD means that there’s no irritating side break. If you’re fond of hearing composers direct their own music, you need this.

The success of In C led to 1969’s A Rainbow in Curved Air, its 19-minute title track an exuberant electric organ solo, Riley making full use of CBS’s facilities by piling on the overdubs, one CBS sound engineer ejected after complaining about this unorthodox use of studio resources. It’s an infectiously upbeat piece, the untuned percussion (dumbec, anyone?) more prominent in the mix as it proceeds. “Poppy Nogood and the Phantom Band” features Riley on soprano saxophone playing over organ. It’s a grower, the solemn organ chord at the close suddenly stopping rather than fading out. Sony include a promo radio ad as a bonus, the voiceover telling us that the album “begins… and ends, and begins again. And if you let yourself travel with it long enough, the same thing will start happening to you…”. As with In C, the remastered sound has huge impact.

The success of In C led to 1969’s A Rainbow in Curved Air, its 19-minute title track an exuberant electric organ solo, Riley making full use of CBS’s facilities by piling on the overdubs, one CBS sound engineer ejected after complaining about this unorthodox use of studio resources. It’s an infectiously upbeat piece, the untuned percussion (dumbec, anyone?) more prominent in the mix as it proceeds. “Poppy Nogood and the Phantom Band” features Riley on soprano saxophone playing over organ. It’s a grower, the solemn organ chord at the close suddenly stopping rather than fading out. Sony include a promo radio ad as a bonus, the voiceover telling us that the album “begins… and ends, and begins again. And if you let yourself travel with it long enough, the same thing will start happening to you…”. As with In C, the remastered sound has huge impact.

Church of Anthrax followed in 1971, a collaboration with John Cale. A publicity photo features a rather bored looking Cale staring impassively at the camera, next to a beaming, seraphic Riley. It’s the most uneven of the three albums, Riley’s contribution to “The Soul of Patrick Lee”, the one vocal number, difficult to detect. Still, the title track is pretty funky and “The Hall of Mirrors in the Palace of Versailles” sounds like vintage Riley. Shri Camel, a solo project, was taped in 1977 and released three years later, the album reflecting the composer’s fascination with North Indian classical music. Riley plays a modified, retuned Yamaha keyboard, at one point using every track on a 16-track recorder. Spacey, elegant, and hypnotic, it’s a brilliant return to form, a big warm hug of a disc. Sony’s production values are impressive, each album presented with its original sleeve art, a thick booklet packed with essays, reminiscences and session information. Buy this before it disappears.

Church of Anthrax followed in 1971, a collaboration with John Cale. A publicity photo features a rather bored looking Cale staring impassively at the camera, next to a beaming, seraphic Riley. It’s the most uneven of the three albums, Riley’s contribution to “The Soul of Patrick Lee”, the one vocal number, difficult to detect. Still, the title track is pretty funky and “The Hall of Mirrors in the Palace of Versailles” sounds like vintage Riley. Shri Camel, a solo project, was taped in 1977 and released three years later, the album reflecting the composer’s fascination with North Indian classical music. Riley plays a modified, retuned Yamaha keyboard, at one point using every track on a 16-track recorder. Spacey, elegant, and hypnotic, it’s a brilliant return to form, a big warm hug of a disc. Sony’s production values are impressive, each album presented with its original sleeve art, a thick booklet packed with essays, reminiscences and session information. Buy this before it disappears.

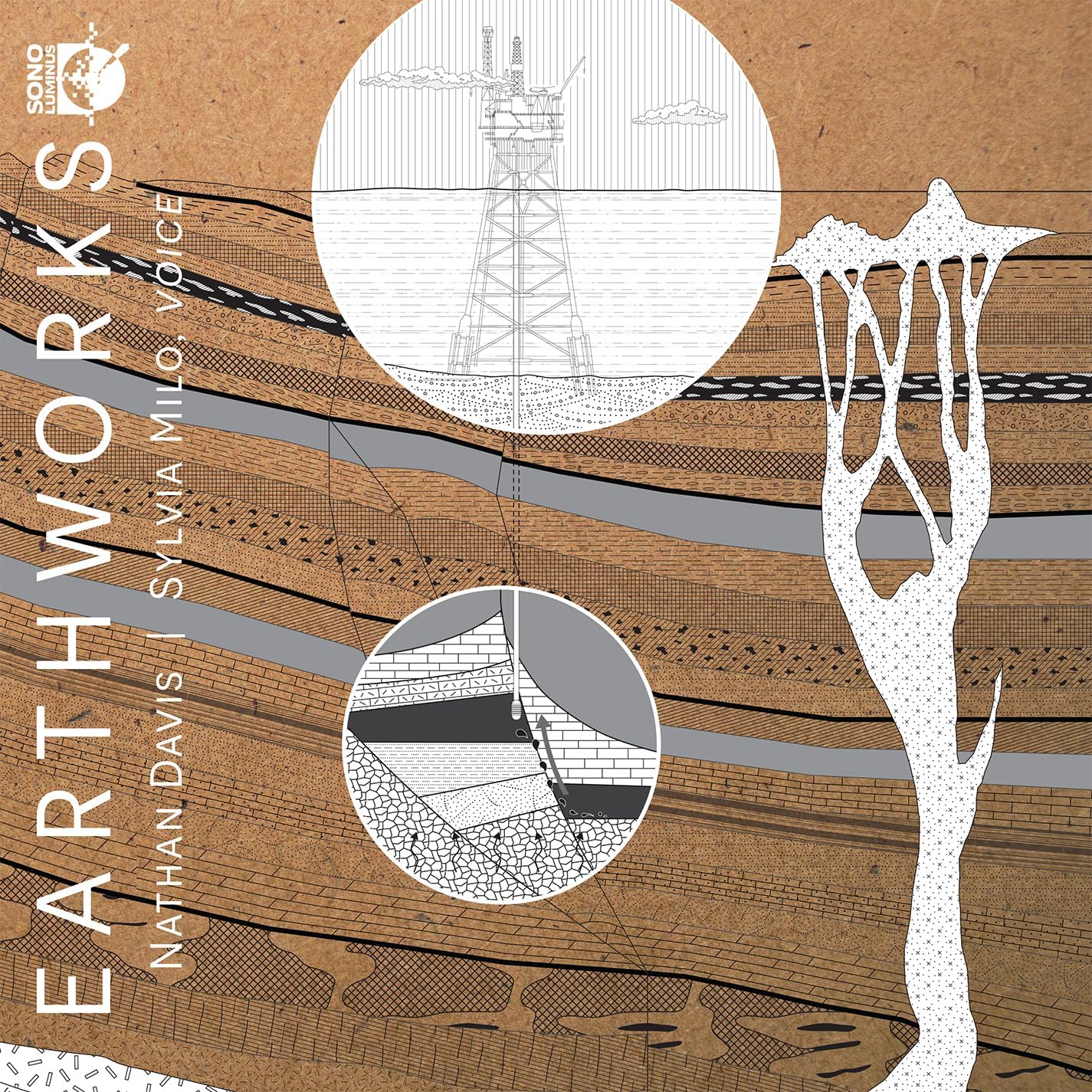

Nathan Davis: Earthworks Sylvia Milo (voice) (Sono Luminus)

Nathan Davis: Earthworks Sylvia Milo (voice) (Sono Luminus)

Here’s an oddity, a 40-minute, seven-movement work which began life as a sound installation for a touring exhibition entitled Planetary Home Improvement: From Just-in-time to Geological Time. An examination of “the geological time of material culture through both physical and digital gallery artefacts”, it contrasts the huge timescales involved in the formation of natural resources with humanity’s total indifference. As the exhibition flyer states, “it takes 1 day to install drywall; it takes 299 million years to form gypsum.” Composer and percussionist Nathan Davis assembled the work from field recordings of the materials in both their raw and processed forms, the first track consisting of actor Sylvia Milo reading a list of album ingredients accompanied by the sounds they make. ‘Galvanized steel sheet’ makes a satisfyingly rich gong-like boom, while ‘polycarbonate panel’ is a flurry of insectile clicks and taps. ‘Crushed stone’ makes a pleasing rasp.

This is musique concrète made with actual concrete, Davis’s gift for layering and manipulating his material intensely musical. There are some extraordinary sounds here – sample the latter stages of the third section, “Weathering”, the eerie scraping heard above a barely-audible rumble resembling a heartbeat. It’s both terrifying and compelling. “Erosion” features the sound of dripping water and there’s something almost brutal about the thumps and crashes of ‘Extraction”. I approached Earthworks with trepidation but was instantly gripped, the album’s rich, immersive sound a key ingredient. One to listen to through headphones.

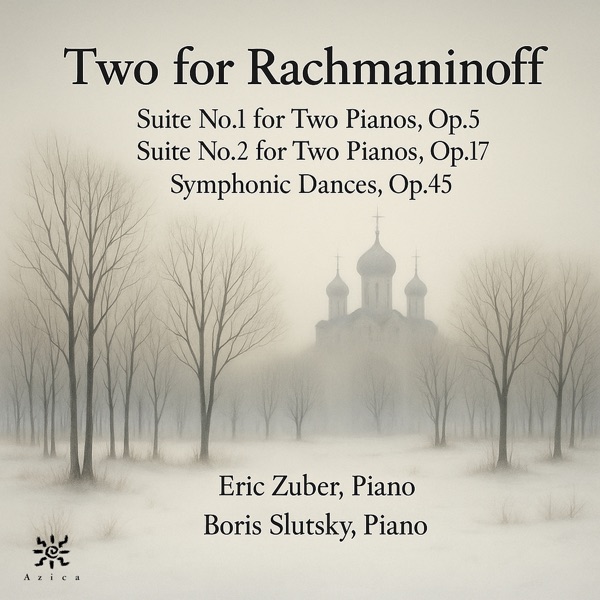

Two for Rachmaninoff: Suites for Two Pianos 1 and 2, Symphonic Dances Eric Zuber, Boris Slutsky (pianos) (Azica Records)

Two for Rachmaninoff: Suites for Two Pianos 1 and 2, Symphonic Dances Eric Zuber, Boris Slutsky (pianos) (Azica Records)

Finding good recordings of music you love by artists you’ve never heard of is one of this job’s best perks. This disc arrived out of the blue, Rachmaninov’s collected works for two pianos performed by Eric Zuber and Boris Slutsky, Zuber formerly Slutsky’s pupil at Baltimore’s Peabody Institute. The playing is terrific, muscular and poetic turns, the pair’s coordination as good as you’d expect from two musicians with an enduring relationship. The works here span Rachmaninov’s career, the early 1893 Suite in G minor dedicated to Tchaikovsky, each of its four movements depicting a different poem. Zuber and Slutsky tap into the music’s strangeness and wildness, the eerie third movement “Les Larmes” disquieting and the bell sounds in “Pâques” full of impact. Suite No. 2 followed in 1901, an outwardly more conventional work, its opening “Alla marcia” full of mature Rachmaninovian fingerprints. Zuber and Slutsky are winning in the lovely “Romance” and the closing “Tarantelle” is exciting.

Nearly 40 years passed before the completion of the Symphonic Dances, Rachmaninov’s self-described ‘last spark’, to me one of the most moving final works by any composer. The two-piano and orchestral scores were composed concurrently, the former premiered by Rachmaninov and Vladimir Horowitz at a private party in 1942. The pair wanted to record it, but, unbelievably, the RCA label declined. A 1970s Decca LP from Ashkenazy and Previn is still my go-to performance, but Zuber and Slutsky are excellent, stressing the work’s (relative) harmonic and rhythmic boldness. Try their jubilant recapitulation in the first dance, the percussive chords at 9’17” full of impact, the tender glancing back at a theme from Rachmaninov’s Symphony No. 1 handled objectively but effectively. The central waltz smoulders, and the finale’s closing minutes are incendiary. No recording venue or dates are listed, though Azica’s bright, clear sound very much suits the performances. Recommended.

Opus 1 – Works by Clementi, Schumann, Chopin, Tchaikovsky, Brahms and Berg Anna Geniushene (piano) (Fuga Libera/Alpha Classics)

Opus 1 – Works by Clementi, Schumann, Chopin, Tchaikovsky, Brahms and Berg Anna Geniushene (piano) (Fuga Libera/Alpha Classics)

It takes something very special indeed for a classical pianist to garner attention among the hundreds of contenders trying to make their way onto the scene, but Anna Geniushene did make a very distinctive mark at the Van Cliburn competition in 2022 – one of only three female finalists since 2010. She emerged as second prize-winner, and as a musician with a different way of going about things, clearly intent on drawing attention to the music itself, rather than to her own pyrotechnics.

There are very few reviews of her around, but a recent one describes her well: “A subtle, grounded musician...at her best in works that have layers beyond the virtuosic.” Geniushene’s previous album was Berceuse (Piano Classics, 2023). To describe this as a wide-ranging programme is a massive understatement: each of its eighteen tracks was by a different composer. And yet, Geniushene has a particularly jaw-dropping way of finding depth and beauty, and flooring the listener with it. Try the surprisingly irresistible “Berceuse” from the film soundtrack Moscow by Leonid Desyatnikov.

The programme of Opus 1 consists exclusively of works published with that designation by six composers: Clementi, Schumann, Chopin, Tchaikovsky, Brahms and Berg. Again, there is an element of the self-imposed straitjacket about the whole idea, but it definitely brings its rewards. I was first struck by her mesmerising account of the Schumann Abegg Variations. There is not just flow and ease, but also light and shade. A virtuosic episode such as the third variation with its cascading triplets stands out above all because it fits so well into the story. There is particular beauty and depth in the Berg Sonata which rewards repeated listening. The Brahms first Sonata has a forbidding opening, what Tchaikovsky referred to in Brahms as "a pedestal without a statue". Geniushene, just like Sviatoslav Richter before her, soon takes us beyond that and into deep and reflective places, particularly in a quite wonderful "andante" second movement.

Geniushene refers to the theme of this album of Opus 1’s as “standing at the edge of something very vast and unknown, to step forward and to say ‘This is who I am’”. The fact that she has ‘genius’ as the first six letters of her surname might not be an accident, and it’s not a huge leap to apply the image of stepping forward to the pianist, and to be mightily curious as to where she herself will land next. I can’t wait. Sebastian Scotney

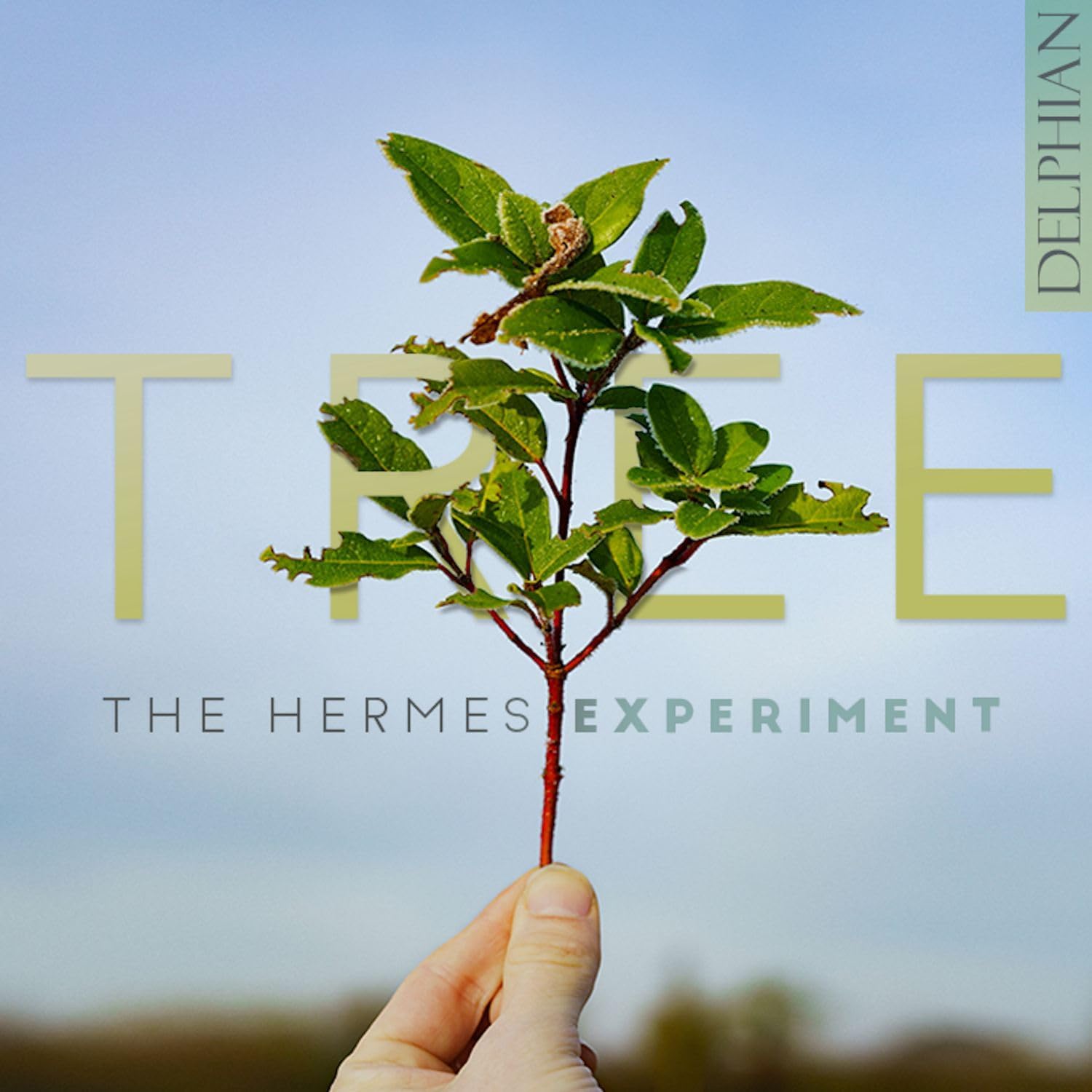

Tree The Hermes Experiment (Delphian)

Tree The Hermes Experiment (Delphian)

The Hermes Experiment is an unlikely combination of harp, clarinet, double bass and voice, the voice being that of the group’s driving artistic force, soprano Héloïse Werner. This third album for Delphian examines nature, memory and change through their distinctive mix of specially written pieces and newly re-imagined existing music. The line-up naturally leads to textures that are fragile, elliptical and elusive, all centred around the infinitely flexible, versatile and intriguing vocals of Werner herself. The tone is generally reflective and meditative – although there are swerves, like the second movement of Laura Moody’s Rilke Songs, which conjures up interwar German cabaret, with an ironic tone and range of musical references. Werner goes from singing “straight” to rasping and groaning: it’s extraordinary, and memorable.

The Elisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre song “Les Rossignols” (originally published in 1694) is re-worked by the bassist of the group, Marianne Schofield, with a free introduction evoking a “gentle dawn chorus”, before the main part of the aria takes the familiar baroque harmonic world and translates it into something timbrally remote. Similarly outré in its acoustic world is Werner’s own composition Thunder Clears, originally a solo song, now garlanded with improvised instrumental lines, “always hushed… blurry”. Other re-workings include Nicola LeFanu’s haunting The Bourne, originally for voice and harp, now expanded, and Hannah Peel’s refreshingly direct “The Almond Tree”. The largest single piece is South African cellist Abel Selaocoe’s Buhle Bendalo, which builds from a floating start to an insistent chanting end.

Although Werner can cut it with the best “classical” singers, the comparisons that kept coming to me were Kate Bush and Björk, not because Werner sounds like them, but she has a similarly eclectic approach to style, the album a collage of contrasting worlds, and because her singing has a comparably wide set of technical resources while remaining completely distinctive. Tree isn’t an easy listen – it demands full attention and emotional commitment – but amply rewards that investment. Bernard Hughes

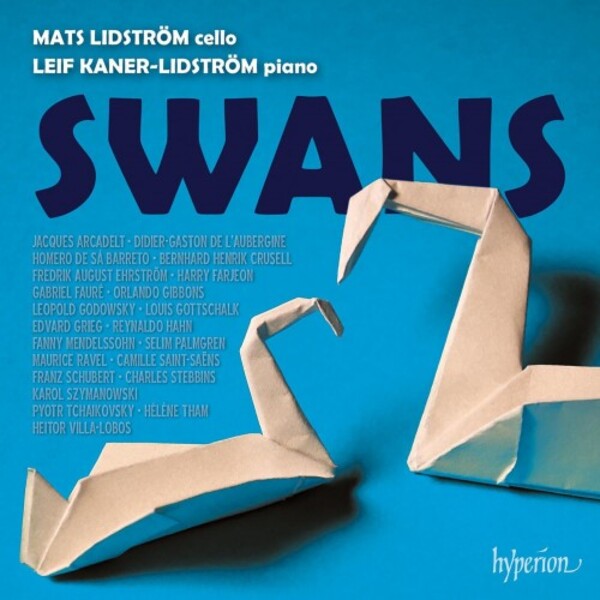

Swans Mats Lidström (cello), Leif Kahner-Lidström (piano) (Hyperion)

Swans Mats Lidström (cello), Leif Kahner-Lidström (piano) (Hyperion)

Think swans and it’s impossible not to think of Saint-Saëns, whose “Le cygne” is the opening track on this lovely disc. Swans is a beguiling celebration of a harmonious father/son relationship as much as an avian exploration, Swedish cellist Mats Lidström partnered with his son Leif. Mats’ detailed booklet essay includes an interesting discussion of what it’s like to have your own child as accompanist: “Would I expect my son always to follow my lead and be given no room for discussion?”. On the basis of what we hear, absolutely not, Mats describing how the music the pair rehearse and perform takes over: “we are there to serve the music, to unspin our powers and commit – no time to ponder over family ties.” Exhaustive research uncovered 23 more swan-themed miniatures, most of them original songs or piano pieces arranged by Mats.

I’d suggest listening to the album in a single sitting before exploring individual numbers in more detail. We get two versions of “Le Cygne”, the second one, pitched a semitone lower, originally arranged by Leopold Godowsky in 1927. Mats’ own “The Swan” is a delectable companion piece, a gently melancholy variant on the original’s aching melody. Compare it with Leif’s identically titled and equally beguiling miniature, opening with a piano inversion of Saint-Saëns’ theme. Fanny Mendelssohn’s “Schwanenlied” is gorgeous, as is a chanson by Reynaldo Hahn, a one-time private pupil of Saint-Saëns.

Especially interesting are numbers by Jacques Arcadelt and Orlando Gibbons from 1539 and 1612 respectively, both sounding disarmingly contemporary in their new colours. I’d never heard of Harry Farjeon (brother of children’s author Eleanor), a former composition teacher at the Royal Academy of Music. His little “Ein Schwanengesang” is delicious, as is “O Cysne” by Brazilian composer Homero de Sá Barreto. I’m barely scratching the surface here and haven’t mentioned gems by Ravel, Fauré, Grieg, Schubert and Tchaikovsky. Plus a 1922 work from an unknown French composer with the most comically French-sounding name imaginable. A protracted online search for more information about Didier-Gaston de l’Aubergine eventually bore fruit, though I’m forbidden to reveal any more. This is a peach of a disc, beautifully performed and recorded – dive in.

Ricordanze: a record of love Musica Secreta/Laurie Stras (Lucky Music)

Ricordanze: a record of love Musica Secreta/Laurie Stras (Lucky Music)

The Biffoli-Sostegni manuscript, MS27766 of the Library of the Royal Conservatory in Brussels, probably acquired by the library in the late 19th century, is a large, fragile, leather-bound book of 78 sacred choral pieces, assembled and copied in Florence in 1560. It was clear (from the layout of the pieces) that it was music for a Franciscan convent of “Poor Clares”, but, till the recent endeavours of academic Laurie Stras, no one knew which convent specifically. Her archival research traced the names of the nuns inscribed on the cover to San Matteo in Arcetri, a few miles from Florence and in the vicinity of Galileo Galilei’s home (his daughters were themselves nuns at the convent).

The 78 pieces – of which a generous 100 minutes is presented in this release – reflect the life and events of the religious life of the institution: mass settings, music for feast days and motets celebrating the joys of virginity. None have a composer’s name, and many seem to be written specially for the higher voices of nuns, often singing a cappella – although some tracks have accompaniment by organ or lute, and occasionally the bass viol stands in for a low voice.

The nine singers of Musica Secreta bring this music to life with a mixture of rigour and affection. There is the academic approach of Laurie Stras, a director of Musica Secreta since 2000, on whose research this album is based, but there is also a love of the repertoire evident in the performances. The number of singers in each item is varied, from the austere three voices of O crux splendidior to the rich eight-voice web of Adoramus te Christe. The instruments blend with the voices beautifully, and the polyphonic vocal lines are spun out with a well-judged ebb and flow. Moments of unison and chordal singing – such as the Dixit Dominus on disc two, offer moments of clarity within the more involved textures. This celebration of music for women (and perhaps by women, who knows?) is lovingly put together and well worth hearing on its own, musical terms – but the historical and scholarly backstory adds further layers of fascination. Bernard Hughes

Add comment