For Black Boys Who Have Considered Suicide When The Hue Gets Too Heavy, Royal Court review - Black joy, pain, and beauty | reviews, news & interviews

For Black Boys Who Have Considered Suicide When The Hue Gets Too Heavy, Royal Court review - Black joy, pain, and beauty

For Black Boys Who Have Considered Suicide When The Hue Gets Too Heavy, Royal Court review - Black joy, pain, and beauty

With boisterous lyricism, Ryan Calais Cameron explores what it means to be a Black man

The title is so long that the Royal Court’s neon red lettering only renders the first three words, followed by a telling ellipsis. But lyrical new play For Black Boys Who Have Considered Suicide When the Hue Gets Too Heavy lives up to its weighty name.

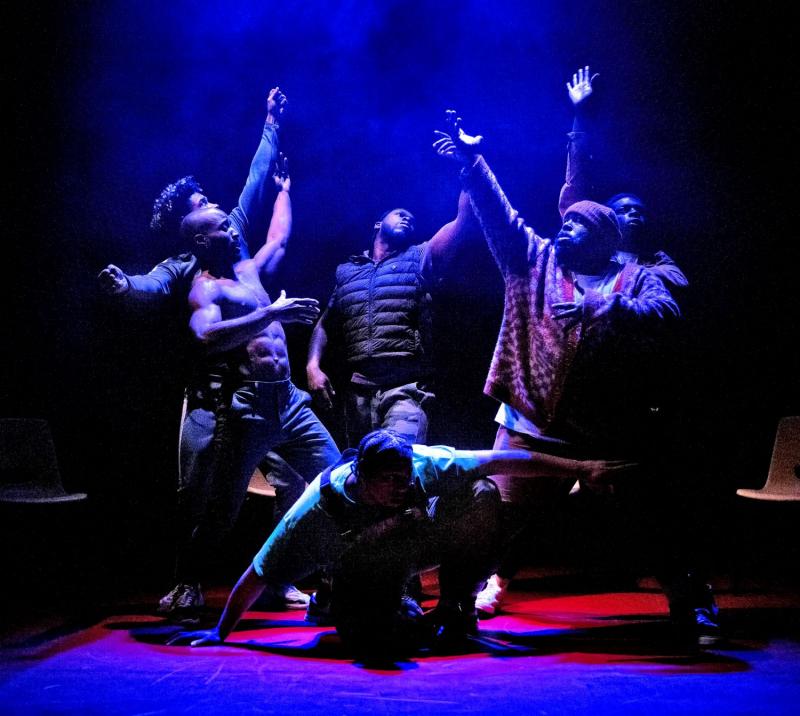

Writer-director Ryan Calais Cameron shows us Black masculinity in all its nuances and contradictions, presented by six actors so naturally charming it’s impossible not to fall in love with them. This is an odyssey through Black masculinity, a complex navigation of a sea of troubles and expectations and joy and love. Line by line, each man’s soul is coaxed to the surface through the stories they tell their peers, laying bare the trauma beneath the bravado.

We start with Jet (Nnabiko Ejimofor) on the playground, wondering why none of the girls go for him when they play kiss chase. The most popular (white) boy in the school takes him under his wing, which six-year-old Jet is thrilled by: “this was before I knew White saviour complex was a ting.” Each character is colour-coded: blue, yellow, orange, red, purple, green. Anna Reid’s set is, too, with plastic primary-school chairs and vibrant walls. The effect emphasises the Black boys’ youth – for some, this is their stage debut. It’s also an element that Cameron has transferred from the inspiration for his play, Ntozake Shange’s For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow is Enuf. Like Shange’s Black girls, Cameron’s boys tag each other into the spotlight, goaded into talking through their trauma even when they’re not quite ready for it.

The effect emphasises the Black boys’ youth – for some, this is their stage debut. It’s also an element that Cameron has transferred from the inspiration for his play, Ntozake Shange’s For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow is Enuf. Like Shange’s Black girls, Cameron’s boys tag each other into the spotlight, goaded into talking through their trauma even when they’re not quite ready for it.

The characters are named for shades of black, for the heavy hue they can’t set down. There’s anxious Pitch (Emmanuel Akwafo), academic Obsidian (Aruna Jalloh), flirty Sable (Darragh Hand), boisterous Midnight (Kaine Lawrence). In bits and pieces, through jokes and rap and rhythm, the boys show their soft underbellies: lack of confidence, low self-esteem, childhood sexual abuse. Onyx (Mark Akintimehin) is the least interested in being vulnerable – or at least, he seems that way at first. His intimidating swagger only cracks when he and Jet begin to act out each other’s father-son dynamics, and it becomes clear just how badly Onyx was treated as a child.

For Black Boys… premiered at the New Diorama Theatre on the corner of Regent’s Park in 2021. Maybe because of being (presumably) written in lockdown, it’s bursting with energy. The individuals are excellent – Lawrence’s heartbreaking reveal of Midnight’s childhood trauma is a standout – but the collective is what’s powerful, here. The myriad dance sequences and singing fit right in, unspooling naturally from the characters’ monologues. There’s an edge to them, though – in a world where Black mannerisms have been copied and twisted for non-Black amusement, the boys remind us that they are singing and dancing for themselves and each other first, and their audience second. It must be almost overwhelmingly cathartic, to perform this show as a Black man, saying the words of a Black man, about Black men. They don’t always agree with each other, of course. At several points, Obsidian reaches towards the other boys’ dance and pulls it down like an imaginary curtain, forcing them to stop and pay attention to what he wants to talk about. “You’re ruining it!” he insists, when Onyx wants to joke around. Through these six contrasting characters, Cameron is trying to work out what he thinks about being a Black man.

They don’t always agree with each other, of course. At several points, Obsidian reaches towards the other boys’ dance and pulls it down like an imaginary curtain, forcing them to stop and pay attention to what he wants to talk about. “You’re ruining it!” he insists, when Onyx wants to joke around. Through these six contrasting characters, Cameron is trying to work out what he thinks about being a Black man.

The confessors’ instinct when they are visibly emotional is to push hands away, but the others resist this, touching shoulders, cupping faces, pressing foreheads to their brothers’ backs. This is what will save them: connection, which stems from vulnerability. Gentle touch, in a world which tries its best to make them brutal. They are each other’s friends, brothers, fathers – even lovers. Ejimofor and Akwafo play out an achingly tender love story in a club, which melts away with the sunrise because their culture sees “homosexuality as a White man’s perversion.”

That glowing red version of the title becomes a neat summary. This play is for Black boys, for the Black boy Cameron was and the Black boys his sons are, for the Black men hiding Black boys inside them. The cast are visibly emotional at the play’s climax, where the characters assert themselves and their humanity. We emerge into a bar filled with portraits of Black boys beaming from ear to ear, as if they’ve been listening in.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Hedda, Orange Tree Theatre review - a monument reimagined, perhaps even improved

Scandinavian masterpiece transplanted into a London reeling from the ravages of war

Hedda, Orange Tree Theatre review - a monument reimagined, perhaps even improved

Scandinavian masterpiece transplanted into a London reeling from the ravages of war

The Assembled Parties, Hampstead review - a rarity, a well-made play delivered straight

Witty but poignant tribute to the strength of family ties as all around disintegrates

The Assembled Parties, Hampstead review - a rarity, a well-made play delivered straight

Witty but poignant tribute to the strength of family ties as all around disintegrates

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Add comment