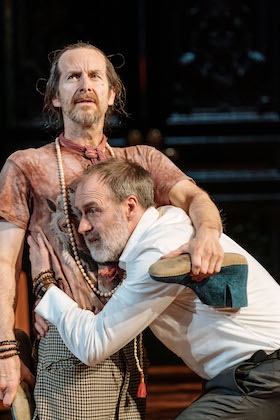

Here's a recipe for a successful National Theatre production: take a well-loved classical comedy, employ an outstanding young director and a talented writer (so much the better if they have a proven track record together) and cast gold-standard actors, including, if possible, someone with a screen presence. What could possibly go wrong? Well, unfortunately, just such a promising mix fails to gel in Tartuffe. Director Blanche McIntyre and John Donnelly were responsible for a well-regarded tour of The Seagull in 2013, while favourite actors Olivia Williams, Kevin Doyle and Susan Engel are among a fine cast joined in the title role by Denis O'Hare (below right, with Kevin Doyle), known for American Horror Story and True Blood.

So what did go wrong? Hypocrisy and fraudsters never go out of fashion, after all; this is the third Tartuffe to hit our stages in little more than a year. In 2018 Christopher Hampton's dual language, LA-set update ran at the Haymarket and the Royal Shakespeare Company's Muslim-context version is just ending its Stratford run. But, whatever the setting, for the modern audience a way has to be found around the fact that religion - except in some pockets of society - is no longer the lightning rod that it was in Seventeenth Century France. When Molière's play, its first version written in 1664, was banned, anti-Catholics could still be burned at the stake. Donnelly has transmuted the traditional notion of religious hypocrisy into a clash of lifestyles. He has not so much updated Tartuffe as spliced Molière's comedy on to his own state-of-the-nation morality play. In this unsatisfactory amalgam we are told, in no uncertain terms, that we are all - audience as well as tricked characters and discovered fraudsters - guilty, and we are addressed several times from the stage to underline the fact.

So what did go wrong? Hypocrisy and fraudsters never go out of fashion, after all; this is the third Tartuffe to hit our stages in little more than a year. In 2018 Christopher Hampton's dual language, LA-set update ran at the Haymarket and the Royal Shakespeare Company's Muslim-context version is just ending its Stratford run. But, whatever the setting, for the modern audience a way has to be found around the fact that religion - except in some pockets of society - is no longer the lightning rod that it was in Seventeenth Century France. When Molière's play, its first version written in 1664, was banned, anti-Catholics could still be burned at the stake. Donnelly has transmuted the traditional notion of religious hypocrisy into a clash of lifestyles. He has not so much updated Tartuffe as spliced Molière's comedy on to his own state-of-the-nation morality play. In this unsatisfactory amalgam we are told, in no uncertain terms, that we are all - audience as well as tricked characters and discovered fraudsters - guilty, and we are addressed several times from the stage to underline the fact.

Orgon (Kevin Doyle) lives in Highgate in materialistic splendour. Robert Jones's sea-blue and red drawing room, which reeks of opulence rather than good taste, includes a gilded copy of Michelangelo's David and a picture of Saint Sebastian which glows either neon pink or green. Tartuffe, by contrast, is a poor immigrant, possibly Polish (although O'Hare's accent wanders) and, until he is taken in by Orgon, living rough. Everyone in the household is either vacuous or venal or both and just about everyone has at least one dirty secret or unethical aspiration. Tartuffe's religion is not a hypocritical version of Catholicism or any particular faith, but a mixture of anything vaguely "spiritual", whatever fits the moment, and before long he has taken over Orgon's life, his home and - almost - his wife and daughter.

While Molière played with the idea of self-delusion as well as the deluding of the gullible, here everyone in the well-off family is wilfully blind and out for personal gain, justifying any means that results in financial comfort. Orgon is provided with a psychological reason for falling for Tartuffe's wiles: he has, apparently, begun to wonder "what's it all for", not to the extent of sharing his goods but sufficiently to lose rationality. Donnelly's happiest invention is to make Valère (eagerly played by Geoffrey Lumb, left with Kitty Archer), suitor to Orgon's daughter Mariane, the most straightforwardly self-deluding of all: a street poet who incites revolution despite being poshly educated and sitting on a stash of cash.

While Molière played with the idea of self-delusion as well as the deluding of the gullible, here everyone in the well-off family is wilfully blind and out for personal gain, justifying any means that results in financial comfort. Orgon is provided with a psychological reason for falling for Tartuffe's wiles: he has, apparently, begun to wonder "what's it all for", not to the extent of sharing his goods but sufficiently to lose rationality. Donnelly's happiest invention is to make Valère (eagerly played by Geoffrey Lumb, left with Kitty Archer), suitor to Orgon's daughter Mariane, the most straightforwardly self-deluding of all: a street poet who incites revolution despite being poshly educated and sitting on a stash of cash.

Orgon's wife, Elmire (Olivia Williams), loyal in the original, here admits to a string of lovers. Donnelly has her claiming, as Molière does, that she can cope independently with unwanted male advances - refreshing - and still relevant - in the era of #metoo. Williams is a joy as Elmire, as she wrestles with Tartuffe, elegant hair awry, to prove his guilt to her slow-on-the-uptake husband. There is strong support elsewhere too, not least from Susan Engel as Orgon's querulous, opinionated mother.

Molière's ending - in which a last-minute messenger from the king prevents disaster - may well have been ironically flattering to the monarchy. That is not the case here: the Prime Minister's intervention makes clear that wrongdoing matters less than being part of the right set. Donnelly's Orgon has more to answer for than Molière's but he still gets off scot-free.

With Molière's play obliged to bear so much extra weight, the comedy is often effortful. It works best in the physical, less earnest, sequences and this is where O'Hare comes into his own - chasing Elmire, losing his trousers, striking a yoga pose - but the laughs are too few.

There is, of course, nothing wrong with being reminded about divisions in society, about our responsibilities to each other (including immigrants and refugees in Brexit-fever Britain), but the finger-wagging is out of kilter with any idea of comedy and is so unsubtle as to be doomed to irritate rather than change minds.

Add comment