Small Worlds, the second novel from Caleb Azumah Nelson, is a delight: a book with a real feeling for sound and dance, and a sense of place from London to Ghana and back again. It’s a story of a first romance, the intricacies of family life, the importance of music, and the difficulties still faced by people of colour in the UK today. While it may not seem like it will set the world on fire, it’s a beautifully observed picture of the twists and turns of life and of love.

Our protagonist, Stephen, is a young black trumpet player, destined for great things until he flunks his exams, forcing a change of plans. In love with his best friend Del and surrounded by music and thrumming social life, the world he lives in seems endlessly open and full of possibilities. When all this changes, Stephen must find new paths and create new worlds. Nelson returns again and again to the sense of expectation that comes from family and friends, and how this defines and constrains him.

The title Small Worlds echoes throughout the book, the spaces that Stephen inhabits (both emotional and geographical) shrinking and expanding to fit their contexts. Stephen’s closest relations live in London, his extended family in Ghana. When his family is discussed, Nelson adeptly illustrates how they can seem so far away from their roots but simultaneously deeply connected to them. Consequently, this is also the story of his parents, first generation Ghanaians who shiver and sometimes starve in London’s inhospitable streets, but over time feel more and more distant from the home country – to which they return these days only for a visit. Their worlds are at once very small and defined by their local communities; but, simultaneously, they can feel massive, expanding with gaps – between family, friends, and heritage – that open up further over time.

Through all of this, the threat of violence remains a persistent undercurrent, mostly manifesting in racist acts perpetrated against Stephen’s friends. Mark Duggan’s murder is referenced throughout, as well as the possibility of experiencing the hatred of others, as his father’s friends do at the hands of the police (in a particularly emotional and successful section towards the end of the book). In these moments, Nelson describes – with aching elegance – how the city shrinks for them, “trying to magic us away, encouraging our disappearance”. Through the story of Stephen’s parents and others, the reader sees how hostile the UK continues to be for immigrants, pushed to emigrate again when gentrification forces them out of their community.

Through all of this, the threat of violence remains a persistent undercurrent, mostly manifesting in racist acts perpetrated against Stephen’s friends. Mark Duggan’s murder is referenced throughout, as well as the possibility of experiencing the hatred of others, as his father’s friends do at the hands of the police (in a particularly emotional and successful section towards the end of the book). In these moments, Nelson describes – with aching elegance – how the city shrinks for them, “trying to magic us away, encouraging our disappearance”. Through the story of Stephen’s parents and others, the reader sees how hostile the UK continues to be for immigrants, pushed to emigrate again when gentrification forces them out of their community.

But this is not the main focus of the book: it is a method by which Nelson can show that a life can contain both beauty and hardship – perhaps, even, that they go hand-in-hand. The beauty is found in Nelson’s compelling descriptions of music: he lists tracks and albums, gracefully elicits their emotional responses in myriad listeners, and shows the profound affect such compositions can have on our environment. Music is a driving force for Stephen, an obsession and a thread that runs through his life. He dances, and Nelson’s expressive accounts bring his movements to life in a way that I feel like I’ve never read. Music is also often how Stephen relates to others, and it ties his family and friends together. (His first love for Del also encompasses the love that they both share for their favourite songs.)

The musicality of Small Worlds seeps into the whole book, with a feeling of inexorable movement. The sometimes disjointed chapters read almost like the sampling that continues to underpin many hip hop tracks, especially J Dilla’s ‘Donuts’, to which the book often returns. This music suffuses the London summers and Ghanaian heat that Nelson describes with loving warmth, the sense of freedom (and, at times, claustrophobia) that fills the city. His is a well-formed, often lyrical book that conjures up a city and a life with delicate and sympathetic beauty.

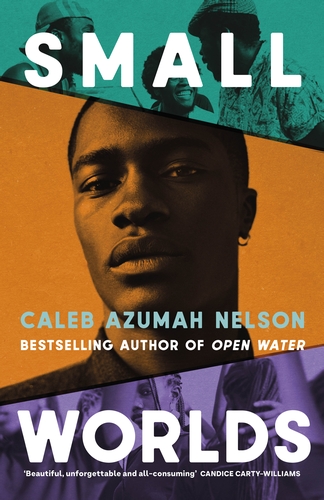

- Small Worlds by Caleb Azumah Nelson (Penguin, £14.99)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment