First the good news: Cédric Tiberghien, master of tone colour, lucidity and expressive intent, playing the 24 Chopin Preludes plus the Bach C major and the C minor Nocturne in the red-gold dragons' den of the Royal Pavilion's Music Room. Then the not so good: Paul Kildea, ruffler of feathers during his brief Wigmore regency and in his sometimes speculative Britten biography, rushing and mumbling his way through excerpts from his new book, Chopin's Piano: A Journey through Romanticism.

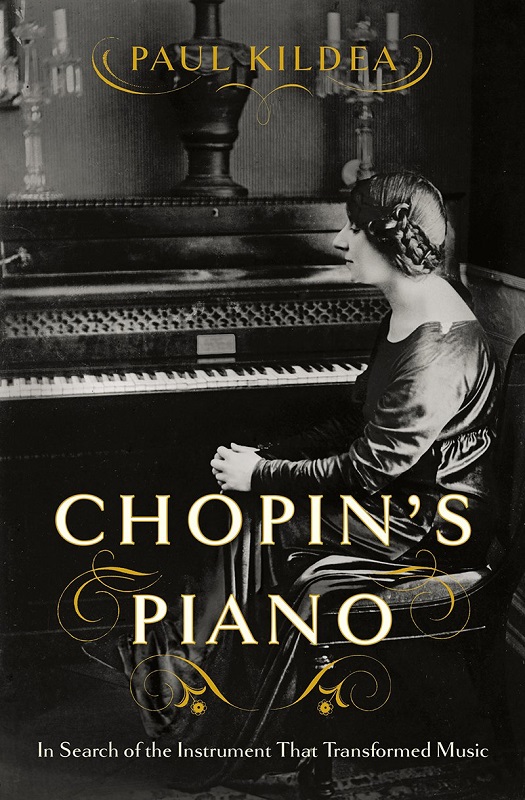

Much interesting material there, though even an experienced actor might have had difficulty making it all mesh with the Preludes, many of them much shorter than the readings which framed them. Undoubtedly it was good to know that the only score Chopin had with him on his ill-fated 1838 winter sojourn in Majorca, about which his companion George Sand wrote so scathingly, was an edition of the Bach Preludes and Fugues, 14 of which Delacroix witnessed him execute from memory. The story of how the pianino made for Chopin on the Spanish island eventually passed into the hands of another great musician, Wanda Landowska, out of them when this self-styled "juive folle de musique" fled her mansion in 1940 and back again is undeniably fascinating (pictured below: Landowska at the pianino on the jacket of the American edition of Kildea's book).  Did we really need the minutiae of Chopin's life in Paris and London, though, mundane against the transcendence of the music? Why so much cultural and historical name-checking as the narrative sped forward through the two world wars? The writing seems for the most part engaging enough, though, even if there are some infelicitous, or infelicitously pronounced, similes (a Prelude 'opening up like a rare orchard'? Really?) And if Kildea was going to read himself, he needed much more confidence when enunciating French and German - you could see an inward panic light going off each time he approached them. Absolute basics: a lectern at a higher level would have kept the head higher and minimised the mumbling.

Did we really need the minutiae of Chopin's life in Paris and London, though, mundane against the transcendence of the music? Why so much cultural and historical name-checking as the narrative sped forward through the two world wars? The writing seems for the most part engaging enough, though, even if there are some infelicitous, or infelicitously pronounced, similes (a Prelude 'opening up like a rare orchard'? Really?) And if Kildea was going to read himself, he needed much more confidence when enunciating French and German - you could see an inward panic light going off each time he approached them. Absolute basics: a lectern at a higher level would have kept the head higher and minimised the mumbling.

But then there was the music. And Tiberghien (pictured below by Jean-Baptiste Millot) created worlds even out of the shortest Preludes. Though ethereal pianissimos are his special gift - moving to tears in the return of the main ideas for No. 6 in B minor and the balm after the central destructive juggernaut of No. 15 in D flat major, a fine link to Landowska holding her head artistically above the horrors of the 1940s - he never over exploits them. He can move from a whisper to a roar in seconds, completely organically, making the beautiful room resonate in thundering octaves, and he combines forward movement with the necessary space. Steinway grands are really made for bigger venues; the icing on the cake would have been for Tiberghien to play on an Erard or a Pleyel (what wonders Roman Rabinovich wrought from Chopin' favourite last year in the Cobbe Collection at Hatchlands). Still, great musicianship makes a virtue out of what's to hand. There were two revelations here: the C minor Nocturne, which made me want to hear the rest immediately, and how the F sharp Prelude; how could I not have realised that this is perhaps the rarest gem of them all?  Needless to say, a single uninterrupted opus would give a much better sense of how Chopin constructs an epic from miniatures (as does his natural successor Rachmaninov - let's bypass Liszt when it comes to profundity). The key relationships, the major-minor dialogues, the sheer variety of moods underlining the self-contradictory human condition - all these need to be heard as a cornucopia of invention. Under the circumstances, it's a miracle that Tiberghien stayed as centred as he did. And the sheer fantasy was reflected in one of the most extraordinary rooms in the world - after experiencing which for an hour and a half we moved into another, the Banqueting Hall, with its even bigger central dragon above the chandelier, to quaff as Prinny would have wanted. Bliss.

Needless to say, a single uninterrupted opus would give a much better sense of how Chopin constructs an epic from miniatures (as does his natural successor Rachmaninov - let's bypass Liszt when it comes to profundity). The key relationships, the major-minor dialogues, the sheer variety of moods underlining the self-contradictory human condition - all these need to be heard as a cornucopia of invention. Under the circumstances, it's a miracle that Tiberghien stayed as centred as he did. And the sheer fantasy was reflected in one of the most extraordinary rooms in the world - after experiencing which for an hour and a half we moved into another, the Banqueting Hall, with its even bigger central dragon above the chandelier, to quaff as Prinny would have wanted. Bliss.

Add comment