Bach: The English Suites Paolo Zanzu (harpsichord) (Musica Ficta)

Bach: The English Suites Paolo Zanzu (harpsichord) (Musica Ficta)

I’m a recent convert to Bach keyboard music played on harpsichord, having recently immersed myself in the Erato box set containing Zuzana Růžičková’s Bach recordings made in the 1970s. Her preferred instrument was an iron-framed modern harpsichord, whereas Paolo Zanzu uses a 1995 copy of a German original built in 1735. It makes a soft, warm sound, his readings of Bach’s six English Suites correspondingly friendly and intimate. With a piano it’s easier to concentrate on Bach’s harmonic arguments, but the harpsichord allows for a wealth of textural detail to emerge. There are ear-tickling moments here. Suite No. 1’s tiny first “Bourrée” opens with shimmering, buzzing clouds of sound, and Suite No. 2’s famous opening number is dazzling in its clarity, the same work’s closing dance refreshingly informal. Zanzu’s Bach smiles.

No. 4’s “Prelude” is all sunlight, and the rippling arpeggios which open the “Sarabande” are sweetly done. Listen to these discs in sequence and you’ll hear Bach becoming more inventive and virtuosic, Zanzu upping his game accordingly. No. 6’s discursive opening movement lasts eight minutes, the flourishes brilliantly played here. And, for all the grandeur on display, Zanzu doesn’t neglect the little details, like the bell-like bass notes sounding throughout the same suite’s first “Gavotte.” An enchanting set, beautifully recorded.

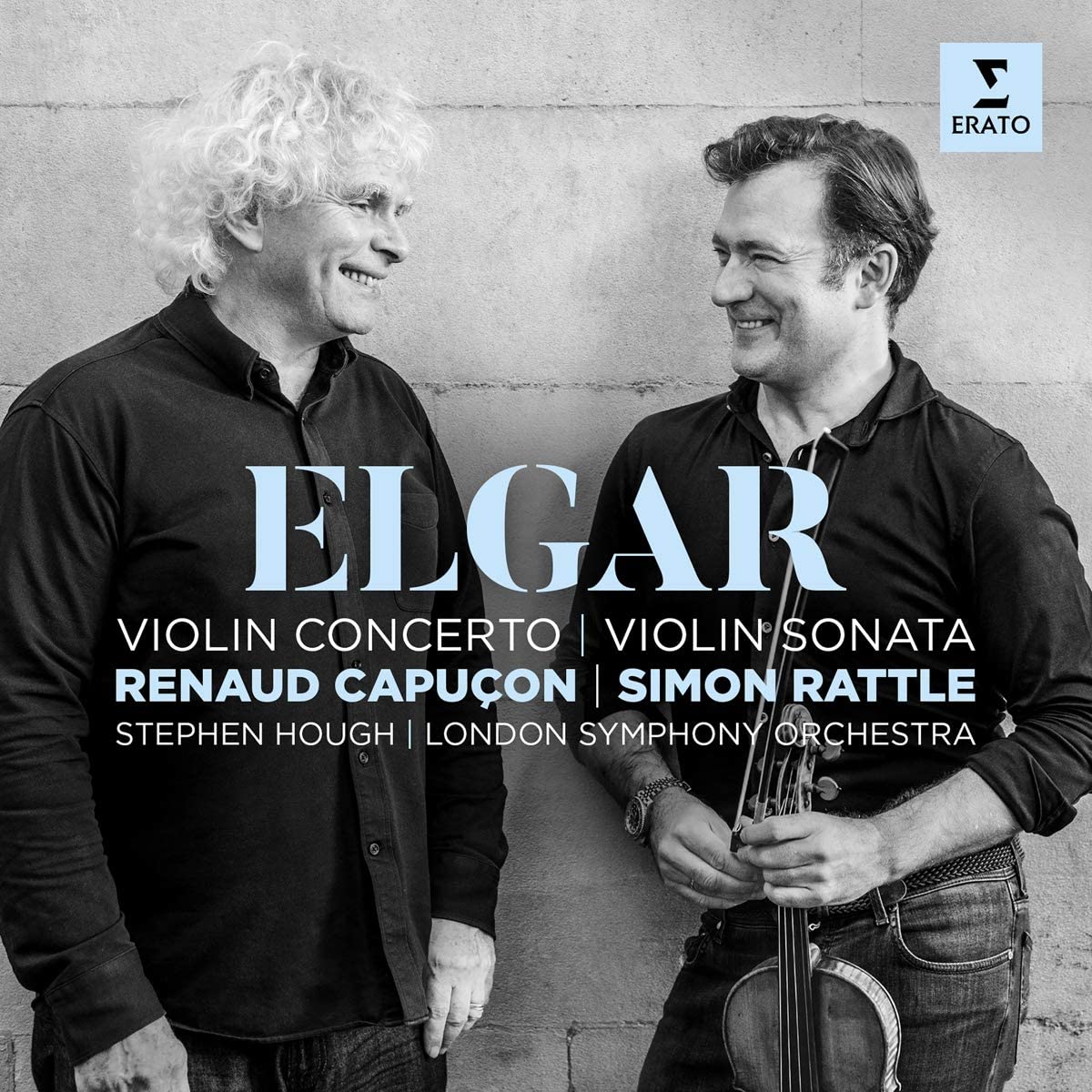

Elgar: Violin Concerto, Violin Sonata Renaud Capuçon (violin), London Symphony Orchestra/Sir Simon Rattle, with Stephen Hough (piano) (Erato)

Elgar: Violin Concerto, Violin Sonata Renaud Capuçon (violin), London Symphony Orchestra/Sir Simon Rattle, with Stephen Hough (piano) (Erato)

Elgar’s Violin Concerto is "difficult" in so many ways. It’s incredibly long (51 minutes in this performance). The solo part is fiendish. There’s a fresh tempo indication every few bars, making it tough to conduct. The tunes, fabulous though they are, take time to sink in. I took part in an amateur performance back when non-professional orchestras could still practice and perform, and vividly remember, after weeks of frustrating rehearsals, when the piece suddenly clicked and made sense, the soloist joining all the dots. Give this concerto time, and you’ll fall in love with it. Renaud Capuçon’s performance hits the spot, capturing that elusive blend of opulence and understatement. The way he steals in after the long intro is magical, as if carefully stepping out of the tutti string section. Capuçon and Simon Rattle’s pliant London Symphony are so well-matched. The orchestral sound is rich but transparent, presumably a result of the sessions being held at LSO St Luke’s last September, session photos showing the players socially distanced.

Capuçon’s playing subtly changes character as the work progresses, the slow climb towards an optimistic ending hinted at by a subtle warming of violin tone. He’s suitably restrained in the central “Andante” and really catches fire in the finale. The elaborate cadenza is brilliantly managed, orchestra and soloist breathing in unison, and the coda packs a real punch. There’s a generous coupling in the shape of the Violin Sonata, with Stephen Hough on piano. Composed in 1918, it’s beautiful, introspective work, Capuçon and Hough especially impressive in the calmer moments; sample the slow movement’s improvisatory introduction, Capuçon’s sighs answered with soft, harp-like piano chords. Good sleeve notes from Ken Woods, with both works captured in detailed sound.

Mahler: Symphonies 1-10 Berliner Philharmoniker (Berliner Philharmoniker Recordings)

Mahler: Symphonies 1-10 Berliner Philharmoniker (Berliner Philharmoniker Recordings)

Mahler wasn’t always ubiquitous. As recently as the 1980s, you could count available recordings of Symphony No. 7 on one hand, and those in search of a complete cycle had to choose between the polar extremes of Haitink and Solti, Bernstein’s earlier New York Philharmonic set being long out of print. The Berliner Philharmoniker’s Mahler tradition began as early as 1892, the orchestra giving the first performance of Symphoony No. 2 three years later. In terms of recordings, there's Barbirolli’s 1964 version of No. 9, heartfelt if technically fallible. Far more consistent are the DG recordings made with Herbert von Karajan, whose taut account of No. 6 still holds its own. This latest set on the orchestra’s own label is a composite live cycle recorded during the last 10 years, the earliest performance being No. 10’s first movement from May 2011 under Claudio Abbado. Harrowing and heartbreaking, the quirky second subject full of life, you wonder why he wouldn’t touch the Cooke realisation of the whole work. The big dissonance has plenty of bite, and Abbado’s tender handling of the music which follows it is deeply moving. There are fabulous things in this set. Simon Rattle’s No. 7 was taped in 2016, a week before a Proms performance given five stars here by David Nice. Rattle has always done this piece well. He’s affectionate and clear-sighted, revelling in the work’s extravagance and eccentricity. The first movement’s development sings and swoons, its jangling coda difficult to resist. Brass are stellar in the raucous finale and Rattle really excels in the crepuscular middle movements. Rattle’s No. 8, from 2011, unwinds at a lower voltage, but has excellent soloists and weighty, incisive choral singing.

Kirill Petrenko places No. 6’s “Andante” second, but I’ll forgive him; this is a taut performance with a swift, ruthlessly effective account of the long finale. The playing has incredible punch and precision. Gustavo Dudamel is temperamentally suited to Symphonies 3 and 5. No. 3’s long opening movement has some marvellous moments, Dudamel letting rip in the Ivesian march sequences. There’s a beautiful posthorn solo from an offstage Gábor Tarkövi in the scherzo and Gerhild Romberger is cool but beautiful in the fourth movement. No. 5’s path from darkness to light is effectively mapped. The Berlin horns nail their unison high whoop in the funeral march’s first trio, and Dudamel’s finale is festive without being driven too hard. He’s excellent in the “Adagietto” too, excessive gloop averted with a flowing basic tempo. Bernard Haitink’s No. 9, recorded in 2017, is very expansive, the opening movement alone lasting over 31 minutes. The control is awesome, the middle movements effective despite their weight, and the last movement’s coda is otherworldly, almost a match for Abbado’s live DVD recording.

And the rest? Yannick Nézet-Séguin’s No. 4 has a good soprano soloist in the finale (Christiane Karg) but the first two movements are underplayed. Things get better in the long slow movement, and it’s good to hear the timpani so clearly in the big outburst near the close. Andris Nelsons conducts No. 2, marshalling Mahler’s extravagant forces effectively if coolly, the performance at last catching fire in the fifth movement. Lucy Crowe and Gerhild Romberger are superb soloists, and it’s good to hear the offstage players so clearly. No.1 is conducted by Daniel Harding, again in a reading which is very decent if lacking individuality. It’s the excellence of the orchestral response that keeps us listening, one of this set’s consistent pleasures. Production values are predictably lavish, the performances also included on Blu-ray discs. Essays from Stephen Johnson and Barbara Vinken are well worth reading, both writers summarising why Mahler is still worth listening to, even if you think you’ve had enough of him. It’s fascinating to compare the various interpreters’ podium techniques on the Blu-ray discs, and you can’t help marvelling at the crowds crammed onto the Philharmonie platform. This set won’t be a casual purchase, but it’s worth the outlay. Treat it like a case of decent wine, as something to be dipped into and savoured.

Monteverdi: Il delirio della passione Anna Lucia Richter(soprano), Ensemble Claudiana/Luca Pianca (Pentatone)

Monteverdi: Il delirio della passione Anna Lucia Richter(soprano), Ensemble Claudiana/Luca Pianca (Pentatone)

This album’s colourful sleeve design is entirely in keeping with soprano Anna Lucia Richter’s vibrant approach; her well-chosen anthology of Monteverdi arias is so sunny, so alive. She’s helped by vibrant support from Luca Pianca’s Ensemble Claudiana, whose arrangements are so witty and apposite. Who’d have thought that Monteverdi could be so funny? Richter is audibly enjoying herself – listen to her drooping “languendo moro” in “La mia turca” – but she knows just how far to push things. Pianca’s blusey archlute intro neatly injects a dash of Turkish ambience into proceedings, and even his final note is a zinger. Then we segue into the first of the four Lamento d’Arianna, fragments from a lost opera, and the mood changes completely, Richter more sober, less flamboyant, but no less expressive. Monteverdi’s word setting is a continual delight. How can this music be 400 years old?

Richter and Pianca give us a near-perfect blend of solemnity and froth. Countertenor (and violinist) Dimitri Sinkovsky joins Richter in “Pur ti miro”, the voices beautifully matched, and how well she interacts with the three-part male chorus in the “Lamento della Ninfa”. It’s all terrific. Andrea Inghisciano’s exquisite cornetto playing enlivens several numbers, and Pianca makes wonderful, sparing use of percussion. Beautifully engineered too; this has already been pencilled into my provisional "Best of 2021" list. Richter’s own notes reveal that the disc was recorded just before Covid put her life on pause (“it feels as if I am listening to my old self, even if it is only a year ago”), and that this will be her last disc as a soprano, having decided to continue her career singing as a mezzo.

Songs for the End of Time Vol. 1 Founders (Founders)

Songs for the End of Time Vol. 1 Founders (Founders)

Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time has been tackled by jazz musicians before, and this disc offers another fresh take on an established 20th century classic. Songs for the End of Time Vol. 1 upsizes the work into a quintet, arranged here by Ben Russell and Brandon Ridenour of New York’s “idiosyncratic quintet” Founders. There’s no piano, the parts now shared between violin, trumpet, clarinet, cello and bass, the five players also doubling up on vocals. So the a capella extract from Revelations which inspired Messiaen is sung at the start of the “Crystal Liturgie” (all movement titles are now in English), and the Dies Irae is intoned over “The Immortality of Jesus”. Arrangement aside, I can’t recall having ever having been moved so much by a recording of the piece. The musical essence is untouched but the rescoring renders the work earthier and more accessible. As with all good arrangements, particular details register with new clarity. Bird calls have extra piquancy played on muted trumpets, and the little interlude at the heart of the work has a mischievous glint.

Hamilton Berry’s cello solo in “The Eternity of Jesus” is as good as any I’ve heard, unfolding over soft violin and bass chords with the winds filling in the gaps. There’s a hint of klezmer in the middle of “Seven Trumpets and the Dance of Fury”, and the miraculous cadence at the close of “The Immortality of Jesus” left me reeling. Extraordinary stuff – if you admire the original, you owe it to yourself to hear this interpretation. Even the engineering is marvellous, the disc taped, appropriately, in a Catholic cathedral in Brooklyn.

Touch Harmonious Nicholas Cords (viola) (In a Circle Records)

Touch Harmonious Nicholas Cords (viola) (In a Circle Records)

This collection is named after Claudy Philips, an itinerant Welsh violinist who died in 1732. His death prompted Samuel Johnson to write an epitaph, referring to a “touch harmonious” so sweet that it “could remove the pangs of guilty power or hapless love”. We need music’s healing powers more than ever in these turbulent times, and this handy package delivers a strong dose in solo viola form. Britten's Cello Suite No. 3 is played here in Nobukai Imai's viola transcription. The original version can sound dour, and it's striking how the viola's lighter timbre brightens the music's mood. Seven of its movements are miniatures, each one well-characterised by Cords, before an extended, valedictory passacaglia finale. Violist Nicholas Cords, a member of Brooklyn Rider and the Silkroad Ensemble, is outstanding, detangling Britten's knottier passages and making the music sing.

Similarly enjoyable is Bach's G major suite, graceful and lyrical here, dancing with a lightness and energy that can be difficult to realise on a cello. "Lascia ch'io pianga" from Handel's Rinaldo is effective, Toshio Hosokawa's transcription creating the illusion that there's more than one player in action. The rest of the disc contains contemporary music. Anna Clyne's Rest These Hands, originally composed for violin, is an extended, lyrical rhapsody inspired by her late mother's poetry. An overdubbed Cords plays both viola parts in Dmitri Yanov-Yanovsky's Short Epitaph, which makes neat use of a chord progression popularised in the baroque era. Dana Lyn's endlessly i would have walked also alludes to baroque string writing but never sounds like vapid pastiche. Cords is impressive throughout, his rich-toned playing full of personality, the intonation impeccable.

- Read Anna Lucia Richter's First Person on the Monteverdi CD and what happened next

- Touch Harmonious on Amazon

- Read more of Graham Rickson's Classical CD reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment