theartsdesk Q&A: Musician John Foxx | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Musician John Foxx

theartsdesk Q&A: Musician John Foxx

The leader of the original Ultravox on challenging the punk era’s orthodoxies and the band as an art project

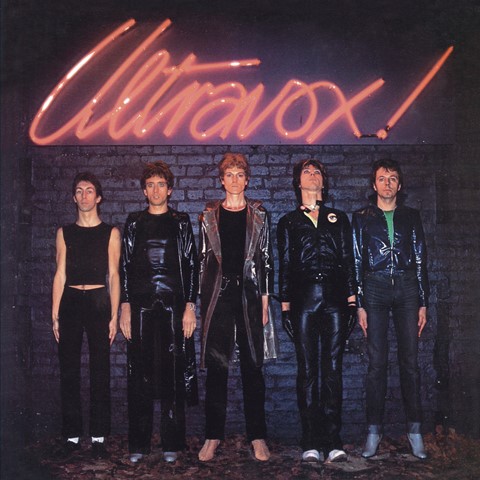

“The best and most confident debut since ‘Anarchy in the UK,’” said weekly music paper Sounds of the debut single by Ultravox! “Dangerous Rhythm” had been released in February 1977. “Cosmic reggae," declared Record Mirror. Melody Maker identified a “rare quality and haunting presence”. The NME said the song was a “reggae abstraction” and “mesmeric”. Ultravox! – the attention-grabbing exclamation mark was ditched in early 1978 – were off to a good start.

Soon, though, the wind direction changed. Stranglers’ bassist Jean-Jacques Burnel said they were session musicians put together by Island Records. In April 1977 the NME whined, “Ultravox are a hype. Just look at their contrived, intense-eyed, PVC punk image.”

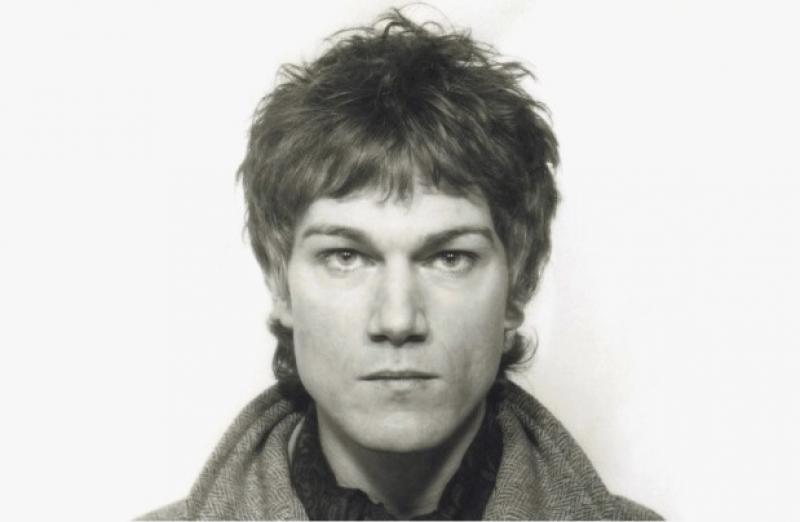

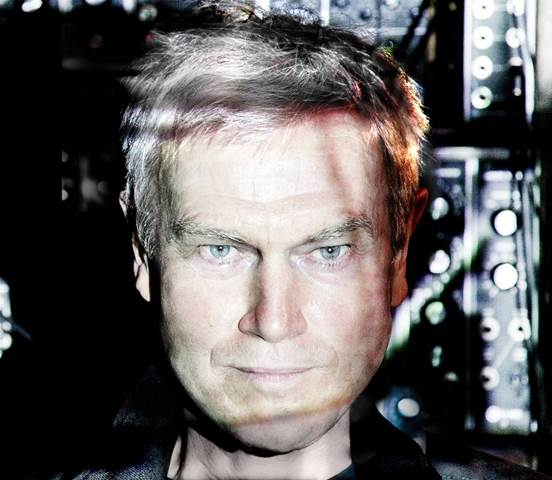

Whether Ultravox were or weren’t punk is now clear. They released three albums in 1977 and 1978, and rode the mood of the time. But the space they occupied was their own. All three landmark albums are reissued today. John Foxx (born 1948: pictured below right, photo by Ed Fielding) has given a rare interview on Ultravox to coincide with their release.

This Ultravox was not the four-piece band which hit number two in 1981 with “Vienna” but a quintet fronted by Foxx – who wrote or co-wrote all the band’s songs – which had come together in 1974. He left in March 1979, and the band regrouped with Midge Ure as their guitarist-singer and moved on. Foxx went solo, hit the charts in early 1980 with “Underpass” and followed his own musical path until 1985 after which he turned his attention to the visual arts and the academic world. Books by Salman Rushdie and Jeanette Winterson have featured his cover art. Following a couple of low-key releases, he returned to music in 1997 with the Cathedral Oceans and Shifting City albums. Since then, he has recorded solo, resumed live work and collaborated with, amongst other individualists, Harold Budd and former Cocteau Twin Robin Guthrie, and continues to work in academia. He was awarded an honorary Doctorate of Philosophy in 2014.

This Ultravox was not the four-piece band which hit number two in 1981 with “Vienna” but a quintet fronted by Foxx – who wrote or co-wrote all the band’s songs – which had come together in 1974. He left in March 1979, and the band regrouped with Midge Ure as their guitarist-singer and moved on. Foxx went solo, hit the charts in early 1980 with “Underpass” and followed his own musical path until 1985 after which he turned his attention to the visual arts and the academic world. Books by Salman Rushdie and Jeanette Winterson have featured his cover art. Following a couple of low-key releases, he returned to music in 1997 with the Cathedral Oceans and Shifting City albums. Since then, he has recorded solo, resumed live work and collaborated with, amongst other individualists, Harold Budd and former Cocteau Twin Robin Guthrie, and continues to work in academia. He was awarded an honorary Doctorate of Philosophy in 2014.

Few people were paying attention when the band which became Ultravox! released their first single in June 1975 under the name Tiger Lily. Foxx – Dennis Leigh as he was – was studying at the Royal College of Art and formed the band after placing a small ad in Melody Maker. Their first gig was in August 1974. The following year's Tiger Lily single was an awful version of Fats Waller’s “Ain’t Misbehavin’.” They signed with Island Records in July 1976 at the point British punk was first being identified, recorded their eponymous first album in September and changed their name. Issued in February 1977, the debut was co-produced by Brian Eno.

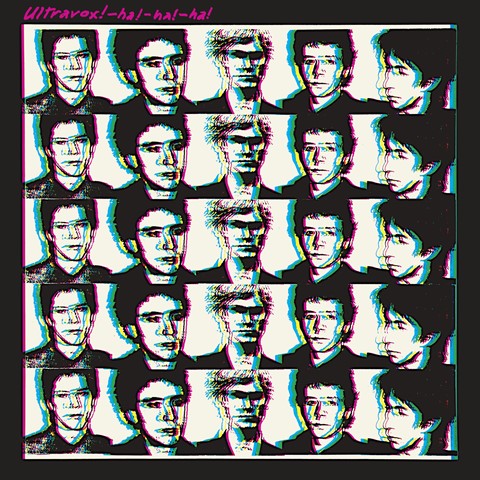

The breakneck, punk-influenced single “Young Savage” followed in May 1977 (pictured below left, with cover art by Foxx). The second album Ha! Ha! Ha! came in October. “ROckWrok”, the single drawn from it, featured the memorable lyrics, “Come on, let's tangle in the dark, dark/Fuck like a dog, bite like a shark, shark.”

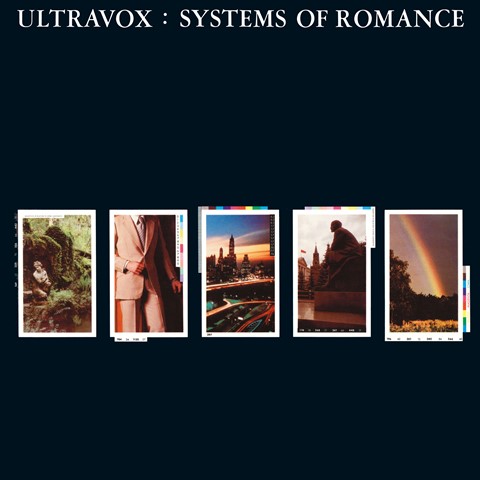

Their third album, Systems of Romance, was issued in September 1978. It was recorded in Germany at the studio of legendary sonic auteur Conny Plank. They were the first British band to record with a producer associated with Krautrock. Gary Numan would soon laud Ultravox as one of his prime influences and the band are now seen as integral to the foundations of British synth pop.

Their third album, Systems of Romance, was issued in September 1978. It was recorded in Germany at the studio of legendary sonic auteur Conny Plank. They were the first British band to record with a producer associated with Krautrock. Gary Numan would soon laud Ultravox as one of his prime influences and the band are now seen as integral to the foundations of British synth pop.

Ultravox had a bumpy ride while Foxx was at the helm. They were not press darlings but their following was so strong they sold out five consecutive nights at the Marquee club. Guitarist Stevie Shears left in February 1978 and was replaced by Robin Simon. Island Records dumped them a month after issuing Systems of Romance. The original band was Foxx (vocals, harmonica and acoustic guitar), Warren Cann (drums: from Canada) Chris Cross (aka Chris St John: born Chris Allen), Billy Currie (keyboards, violin: he had joined Tiger Lily in late 1974) and Stevie Shears (guitar).

The three John Foxx-period albums tracked a band which was developing quickly and sounded like no one else. Literate lyrics of urban anomie and alienation were balanced against explorations of – before Kraftwerk – the relationship of man and machine. The freeze-dried Ultravox! had whiffs of Roxy Music, JG Ballard and William Burroughs. Ha! Ha! Ha! was mostly dense and abrasive but featured the beautiful “Hiroshima Mon Amour”. The warm Systems of Romance defined a music incorporating synthesisers which retained the power of rock and was imbued with the romance of nostalgia and yearning. It also, despite being recorded in summer 1978, sounds like a template for various strands of British music from the 1980s. It is arguable that without John Foxx’s Ultravox there would have been no Simple Minds or, even, Duran Duran.

KIERON TYLER: You formed the band by placing a small ad in Melody Maker in 1974?

JOHN FOXX: It mentioned Billy Fury, the New York Dolls and said it was to rehearse for playing six weeks from now. Billy Fury was the first English rocker to write his own songs and I liked him for that reason. It was going to be an English version of the Velvets mixed with the New York Dolls. I felt the Dolls were directly in line with the Velvets. Roxy Music had picked up on the Velvets, so had Bowie. The Velvets were the only band which had got close to blues, modern blues. I really liked John Lee Hooker and Little Walter. I had been really disappointed when I came to London and I was raring to go, and everything seemed to be dead. I didn’t want to go through the pub rock scene. Pub rock was exactly what I didn’t want. There was a band called the Winkies who were interesting. I didn’t ask anyone who answered the ad to play. The principle was anyone with a modicum of skill could do it, that was the point. I wanted people who felt right, and who had the right sort of style and ideas. The only person I asked to play was Warren, the drummer. Drummers varied in quality, so I asked him to play.

It was your band.

It was your band.

Yes. (pictured right, Tiger Lily in 1975)

How did you choose the name Tiger Lily?

That was Warren’s idea. We didn’t have a name and I couldn’t think of one. He had this décor from the Fifties and a picture of a woman on the back of a tiger. That was a time when we had a name every week: The Zips, Fire of London. The Damned was one of them. We weren’t gigging, so it didn’t matter.

What led to making the single as Tiger Lily?

We knew this great guy called Austin John Marshall. He’d had done something to do with Jimi Hendrix and wasn’t a manger as such, an old London bohemian type who was a copy writer in Soho. He was married to [folk singer] Shirley Collins. A friend of his had done a porn film by stitching together a lot of these 1920s films which is how we came to do “Ain’t Misbehavin’” [as its theme tune] which gave us enough money to buy Billy an electric piano. “Ain’t Misbehavin’” was terrible, but it’s what they wanted. We were broke at the time. I spent all my grant on equipment.

What did you live on?

What did you live on?

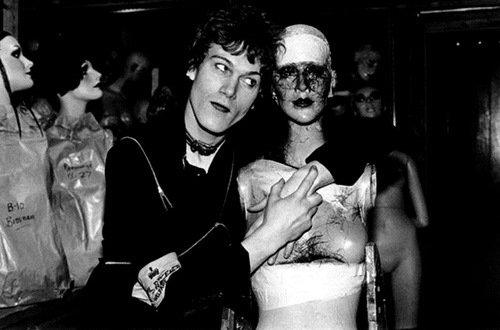

I used to paint dummies. It was what art students did. Shop window dummies. I painted their faces [the band rehearsed in a mannequin factory in King’s Cross]. Chris was on the dole. I think Billy was too. Steve used to work in factories in Dagenham. Warren...I’m not sure. (pictured left, John Foxx with one of the dummies in 1977)

Were you aware something was coming along that was not pub rock?

Oh yes, everyone in London did at that point. We had been into [Malcolm McLaren's shops] SEX and Let it Rock before that. We used to see people around. For example, at the [May 1976] Patti Smith gig at The Roundhouse I saw Mick Jones and he looked like a guitarist. I thought of asking him to be our guitarist but thought anyone who looks that good can't play. He looked great, like a young Keith Richards. He and Glen [Matlock] came to see us play. I felt there was something to be developed that had the spirit of the time. It was one of those periods where the spirit of the times was not being represented. London, even in books, literature and art, didn’t have an image in people’s minds. A slightly lost city. Later on, people like Ackroyd got London sorted in terms of mythology. But back then there was nothing. There were hints of a spirit of sub-level regeneration, but nothing was really consolidated.

I never aimed at any audience. I was trying to make music I wanted to hear

You saw the Sex Pistols?

I thought they were great, really rough. I liked they style, it was really exciting. I saw them at the 100 Club. I was on a bus going down Oxford Street and saw these likely characters going in and thought, that should be good, so went down. There were only about 20 people there.

You signed with Island in July 1976.

The connection was already there. I’d been to Island with some demos in about 1974. They said, "Come back when you’ve formed a band." They were probably saying clear off but I thought, yeah OK. They didn’t commit [to the band] for a little while. I was told, “We’re not sure what you are, but it sounds like it might go somewhere.”

Did you have any idea of who your audience might be?

People like us, whoever they were. I never aimed at any audience. I was trying to make music I wanted to hear, trying to distil this thing all the time. You keep on going and it changes all the time. The horizons always fell away.

Did Island try to push you in any direction?

No, God bless them. They didn’t. They weren’t sure about the name Ultravox. They thought it was a bit weird. I just wanted us to sound like an electrical product. They thought it was too stark, too unfriendly. I changed my name at the same time. I was from Lancashire, an ex-art student. I needed to design someone who could cope with what the job was. I didn’t think the previous guy was up to it. So it was important to design someone else. For me, the whole thing was an art project. At the Royal College we’d been talking about this idea Design for the Real World [Victor Papanek’s book of the same title was published in 1971] and how art is not art unless it works in the real world.

Why are there two xs in John Foxx?

From Charlie and Inez Foxx, who I’d seen supporting the Rolling Stones in Wigan.

The first album (pictured right) is credited as co-produced by the band, Steve Lillywhite and Eno.

The first album (pictured right) is credited as co-produced by the band, Steve Lillywhite and Eno.

Steve Lillywhite was a friend of either Chris of Billy. He had just graduated to being an engineer from a tape op and he was happy for us to come in to the Marble Arch studio he worked in at the weekend and evenings and record us. We worked there for about six months stealing time. Steve became one of the gang. Steve would record the sessions. He was an enthusiast and came with us to Island. Eno was around and a bit lost after Roxy Music and came via Island. I liked Brian a lot, he used to come into the Royal College of Art a lot, sometimes in his Roxy gear which I was thought was very endearing. He was going out with a ceramicist studying there. I knew him by sight, liked his ideas. Steve had recorded about half the album and then Brian came in and we did “I Want To Be a Machine” and "My Sex” with him, so we shared the production credits. We finished that record in September 1976. It took three weeks to record. By the time it came out we had already written new songs.

The first album doesn’t quite stylistically cohere. “Dangerous Rhythm” is reggae. “Lonely Hunter” has a funk influence.

In some ways it did. In some ways it didn’t. It’s a mistake new bands can make to try to show everything you can do. I wanted to get some reggae and dub feel. Chris had been brought up with the music and was a very good heavy bass player. So I wrote a song around the bass. The same with “Lonely Hunter”, also written around the bass. “I Want To Be a Machine” was more my area.

Live, the band had a much more enclosed sound than on the album.

Live, the band had a much more enclosed sound than on the album.

It was a reaction to the times of course, but it was also focusing what we were doing. We needed to concentrate on what we felt we were best at. I wanted to get the theme of what we were doing right rather than put all our favourite dinners in one place. We were not fixed. It took a lot more work, two albums, to get it distilled. (pictured left, Ultravox in 1977)

How long did you think you would last?

The plan grew. My original plan was to make one album and I was going to walk away after that. But of course, when you’ve worked with someone the relationship has built. We then had a five-year plan. In the fifth year, we would be touring America.

On the first album's “Wide Boys", who were the people in the lyrics who were “delightfully unpleasant with their poxy adolescent sneers”?

That was us. We used to walk around London, have a drink. That was reporting back.

Was “Young Savage” reportage?

That was about someone I knew. A friend of mine had a son who was a bit of a tearaway and was in a gang who used to break into houses. They were all about 14. They were always in trouble and some of them lived rough around London. It was like something out of Dickens, like the way McLaren later tried to portray the Pistols. It was unbelievable. This gang numbered around five or six kids. They used to push him in through windows as he was very small. It felt like savagery, the gang were young savages. It felt like the times. The two things came together neatly.

Live, you were extremely loud. Very loud.

Live, you were extremely loud. Very loud.

We wanted to be the most powerful band you could ever be. It was a sonic attack, a proto-industrial music we were trying to make. An extension of punk. I wanted to record that sound and on [second album] Ha! Ha! Ha! (pictured right) we wanted to see how abrasive and aggressive we could sound. It partly worked. Island were shocked, they couldn’t understand what we were about. They had Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers, and Bob Marley had broken through. All the energy of the company went in that direction. We were standing on the side watching. We played the Marquee a lot which allowed us to develop our own little world.

Did you then get a sense of who your audience was?

All the people who had been attracted by punk but weren’t satisfied by it. There was a generic punk sound based on the Ramones, Pistols, etc. We didn’t want to be pigeonholed or shoehorned into that. We felt like we were part of that scene but also tangential, deliberately so. Everyone else is doing guitar music – let's bring a synthesiser in, you can make extreme noise with a synthesiser. We had been experimenting with feedback and wanted to extend that. We built a bass cabinet for Bill’s synthesiser. I wanted to try to make people sick with the bass but we didn’t manage it. I wanted all that noise, violence and art in the framework of songs. We began to find people who liked what we did.

I realised the real impact of emotion is not being dramatic, but when it’s withheld

You began using a drum machine.

We first used one on “My Sex”. There’s a bass drum pattern we used that came from Brian. We had tried to record a heartbeat initially but it didn’t sound good enough. Brian also had an early cocktail cabinet TR77 [rhythm machine] and Warren enjoyed playing with it. I bought one after the first album. So I wrote “Hiroshima Mon Amour” with the drum machine I had at home. I said to Warren, “You operate it.” I thought he might be offended but he wasn’t, he really enjoyed doing that and, live, would play drums with it. There were a lot of things I was trying to do at the time and one of them was the idea of romance and the machine going together. It had sprung from the idea of “I Want To Be a Machine”. Then I realised the real impact of emotion is not being dramatic, but when it’s withheld. When you sense someone is withholding emotion. When they don’t want to display it, it's much more moving than displaying it.

“Hiroshima Mon Amour” has a sense of nostalgia.

You can feel a nostalgia for things that haven’t even happened. It's about how things might turn out. They turn out a different way and move off into the past. a retro-future you look back on. A strange emotional involvement with something that never happened, the lost worlds.

You first played continental Europe in 1977.

We played a residency at the Club Gibus in Paris in 1977 and there was a faction of very serious students who used to come and watch us and wanted to talk about philosophy afterwards. We toured Germany a lot. We dropped in to Conny Plank's studio when we were touring Germany as Brian was there working on Music For Airports, and also working with Holger Czukay. It was interesting to see how great Conny was. He had chairs with tubular legs around the room and was running tape loops around them. He took infinite pains and I thought, this is the guy. I was starstuck.

Why did Stevie Shears leave?

Why did Stevie Shears leave?

I think we needed to expand. We weren’t getting on. There was a blow-up at one point on tour. In many ways the problem was I'd seen Robin Simon in another band called Neo and Billy was keen to work with him as well. I thought that’s more us than any other guitarist I’d ever seen. He could do things no one else was doing at the time, a unique way of playing. He doesn’t play clichés. Organic, shape-shifting – you could almost see the thing in 3D. Until Robin came along, there was no else like that. John McGeogh [of Magazine] was maybe the only one. In Germany, Michael Rother, but he was a completely different type of guitarist. The band is greater than the sum of its parts. We had “Let’s have an adventure" as slogan, the other slogan was "No one's indispensible." (pictured left, Ultravox in March 1978)

Was it hard to convince Island to let you record on Germany with Conny Plank?

Luckily, we had a great new A&R guy and he liked all that German thing as well. He thought it was a good idea: a good idea for the band, good for everybody. We rehearsed for three weeks before we went away. The only song written in the studio was “Dislocation”. Staying there meant we were free to work 24 hours a day. It was about three weeks.

We felt punk was dead by 1977

As well as the idea of romance and the machine going together, what other things fed into Systems of Romance?

Ha! Ha! Ha! had attitude that this was the end of punk, we felt it was dead by 1977. We had this noise thing working for us with Ha! Ha! Ha! and then we distilled it into electronics. Ha! Ha! Ha! described that arc, what the future was going to be. I felt that was the direction for us. As soon as we got “Hiroshima Mon Amour” down I thought, that’s it, that’s what we have to pursue. It totally coincided with Conny, totally coincided with Germany, synthesisers, the new form of song, the machine-romantic and being powerful without being obvious about it.

Did you realise you were writing the script for the future of British pop?

No. I didn’t. That wasn’t the intention. What I wanted to do was find a space that no one else occupied. I thought with “Hiroshima ” we got there, we had our own space and we could develop it.

Parts of Systems of Romance (pictured right), like “When You Walk Through Me”, seem influenced by The Beatles. It's there on some of the drumming which is like “Rain”.

Parts of Systems of Romance (pictured right), like “When You Walk Through Me”, seem influenced by The Beatles. It's there on some of the drumming which is like “Rain”.

It’s absolutely true. I always thought that “Tomorrow Never Knows” was the future of pop music. I was at a party at an art school up north and someone came in with Revolver the day it came out. We played it all night, but the track we played all night was “Tomorrow Never Knows”. Eight hours of “Tomorrow Never Knows”. It was bloody wonderful. I thought that's the best song I’ve ever heard in my life. It sounded like what Pink Floyd wanted to sound like. I thought that was the most adventurous music on the planet at the time: George Martin and The Beatles. I always kept that in mind.

What was your reaction to Systems of Romance when you heard it played back for the first time?

It was pretty close to where I thought we should be as band. It was the first album I was satisfied with – as satisfied as you can be. That was the journey, to get to that point. We didn’t discuss it. Island were a bit bemused, hopeful.

Did you think it could be challenge to do it live?

No. Everyone was so good. Warren was a great drummer, and operating the drum machine and playing with it live. Chris was great player, with ideas. He was doing Mini-Moog bass. Billy was a first-rate synthesiser player, who played synthesiser not imitating other instruments. Robin was the best guitarist. It was a mighty powerful organic unit at that point.

I'd decided I wanted to leave before we recorded 'Systems of Romance'

Why did Island let you go?

We didn’t sell enough records. We went in for a meeting, the managing director had already explained they couldn’t keep us. I was pleased. I wanted to be off the label and get us to somewhere that liked what we were doing.

Even though you were not on a label, you toured America in early 1979.

Stewart Copeland’s brother [Ian, rather than Miles] ran the agency IRS and discovered that a certain generation of Americans liked what was coming out of England, so he had set up a touring network of small clubs. Quite rough and ready. There was an audience ready to see the latest wild animals from England out of curiosity. It was great fun.

The tapes of these shows point to your future. The sound is very electronic and you were performing "He’s a Liquid” and "Touch and Go”, both of which you would record solo..

I’d decided I wanted to leave before we recorded Systems. It had begun to feel that bands were changing their form. It was possible to make a record with one finger on a keyboard, a drum machine and tape recorder. It really interested me. It felt like the beginning of a new kind of event taking music in a new direction. There was a job to do, devising a new language for the new instruments.

I really liked Gary Numan and Tubeway Army, probably more than anything else at the time

You left, they continued as a band.

I didn’t want it to finish. Robin stayed in New York. It was something I had designed, but it had people. I said, "Take the name." It was theirs. I felt what Midge had done was a very skilled conversion of what we had arrived at into a more popular form.

What did you think when you heard Gary Numan and Tubeway Army?

I really liked it, probably more than anything else at the time. I enjoyed the simplicity of it. Gary had distilled everything from that era… it was like the blues. I love something that’s simple and can’t be simplified further. Once you have that, that’s real music, that’s the Holy Grail for me. Something that can’t be stripped down any more.

Did you have any inkling the solo you would end up on Top of the Pops?

Not really, but the times were changing. Suddenly Gary had a hit record.

What does it feel like looking back from 40 years on?

We were lucky as we were part of a time when things were changing very quickly. It was a tremendously rich, fast-moving time and in that time we covered an awful lot of ground. We made ideas real. Working with other people towards an objective is a fantastically powerful thing and you release that the band is bigger than you. It feels like we set out to do something and succeeded. We set out to have this adventure and we did. It took us out of our previous lives and gave us new ones. I’m pleased the band made a success out of their version of it. It gave us the freedom to do what we wanted to do.

- The reissues of Ultravox!, Ha! Ha! Ha! and Systems of Romance are released today

- Read more music interviews on theartsdesk

Buy

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Emily A. Sprague realises a Japanese dream on 'Cloud Time'

A set of live improvisations that drift in and out of real beauty

Emily A. Sprague realises a Japanese dream on 'Cloud Time'

A set of live improvisations that drift in and out of real beauty

Comments

I just want to congratulate

I just want to congratulate Keiron on this interview.

Well researched, well written and very readable. Really brings out some wondeful anecdotes form Foxx

Thanks for sharing it. A really good piece

Excellent interview with a

Excellent interview with a modest legend ! Almost forgets to blow his own trumpet ! Buy the ultravox reissues now ! With a great extra disc of raritys and john peel sessions

There are always some more

There are always some more layers to the Ultravox onion to peel back. Thanks for giving us some new looks back at that era with Foxx. After 35 years I suppose I'll have to cart my carcass at great expense over the Atlantic if I ever want to see Foxx live. I just hope The Maths reconvene for some more live work and recordings beyond the "Machine Stops" soundtrack.

Excellent interview. Perhaps

Excellent interview. Perhaps in the future we can also hear John's comments on his solo records The Golden Section and In Mysterious Ways, which were nicely reissued a few years back, too. I still have them on cassette!

Very pleasant reading. The

Very pleasant reading. The first comprehensive interview about Ultravox’s first era I read given by one of its musicians. Happy to know how the band was created with details I didn't know.