Fans of American playwright Annie Baker’s work know what they are likely to get in her film debut as a writer-director: slow-paced interactions between characters thrown together in a confined space – a workplace, a B&B, a clinic – where long bouts of silence are not uncommon and little happens but everything important somehow gets said.

Janet Planet is classic Baker in this respect. In some scenes, the birds and crickets make more noise than the humans, and whirring fans get solos. There’s also music, a rarity in a Baker stage production, here mostly coming from car radios or home stereos, but also live at barn dances and woo-woo outdoor theatre performances. Some of it is great music, too, such as the high-octane country fiddling and the Schumann string quartet on the radio. Noise is crucial here as it reflects the sensory world our heroine experiences, one she feels ill at ease in. The world she can control is a little cupboard full of figurines and knick-knacks, across which she can pull a curtain.

For our heroine is not Janet Planet (Julianne Nicholson) but her 11-year-old daughter Lacy (Zoe Ziegler). Janet is a licensed acupuncturist living in a bucolic forested area, in a house with hippyish leanings. Janet, we will learn, has had many boyfriends, currently a moody one called Wayne (Will Patton). Lacy is a fledgling piano student, robotically making her way, on the white keys only, through volume one of her practice pieces. She is not, alas, naturally gifted but earnestly plods on, trying out tunes on a portable keyboard at home. It's self-expression, perhaps, but not as we know it, stilted and passionless.

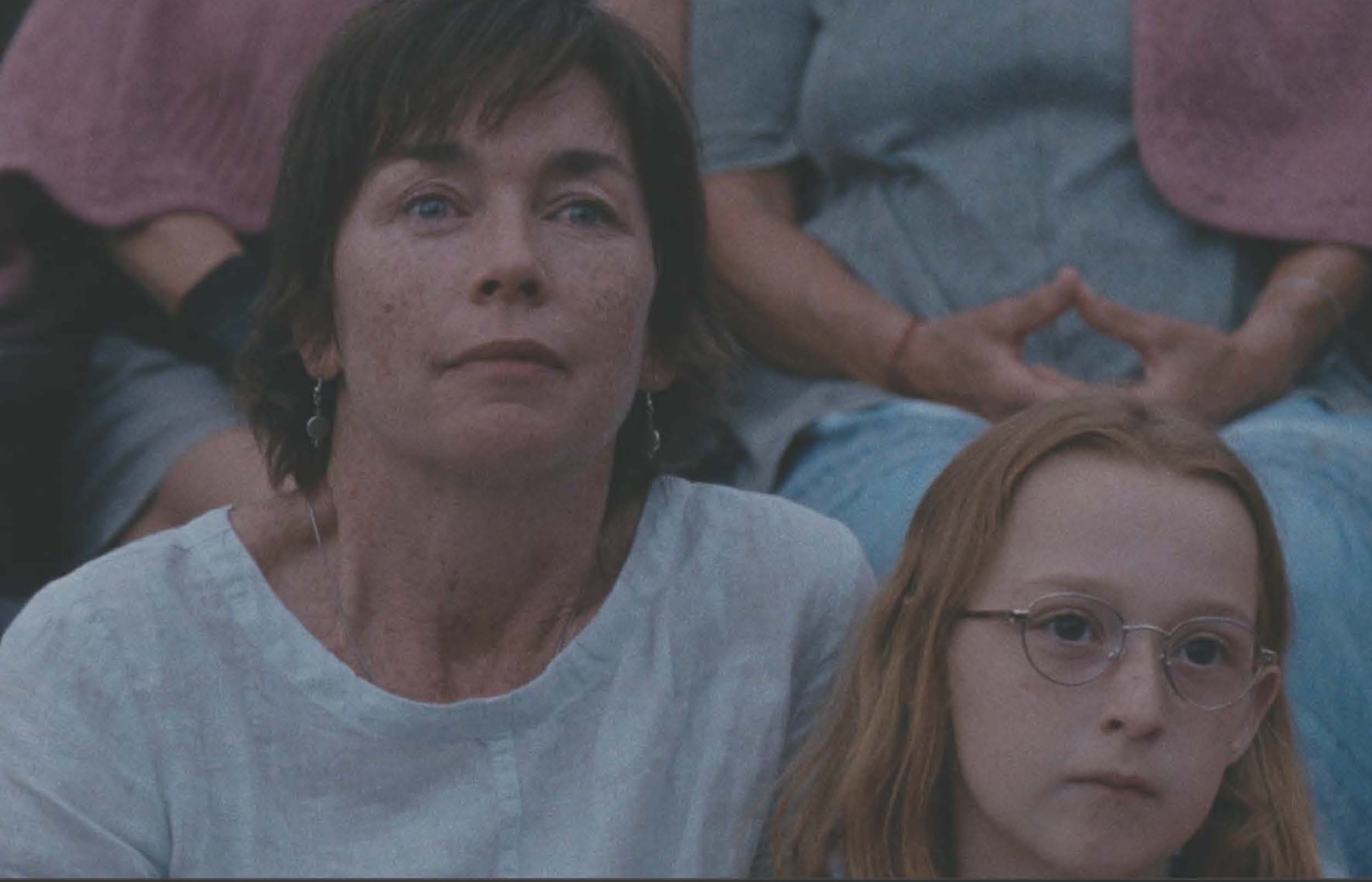

Janet seems a kindly but rather remote mother, giving Lacy a degree of leeway that perhaps borders on lack of proper attention. She has nabbed the film’s title, but it’s Lacy's point of view that dominates, a window on the way she sees the world, though often as details —Janet’s earring and Wayne’s stubble, seen from the back seat of the car, or Janet’s bare freckled legs from Lacy’s viewpoint under the kitchen table. Lacy is circumspect, often taciturn, her sharp features giving her the look of a watchful, slightly disapproving bird. We are scrutinising her, but from behind her granny-glasses she is sizing up her mother and the rest of the adult world.

Janet seems a kindly but rather remote mother, giving Lacy a degree of leeway that perhaps borders on lack of proper attention. She has nabbed the film’s title, but it’s Lacy's point of view that dominates, a window on the way she sees the world, though often as details —Janet’s earring and Wayne’s stubble, seen from the back seat of the car, or Janet’s bare freckled legs from Lacy’s viewpoint under the kitchen table. Lacy is circumspect, often taciturn, her sharp features giving her the look of a watchful, slightly disapproving bird. We are scrutinising her, but from behind her granny-glasses she is sizing up her mother and the rest of the adult world.

She has many questions, few of which are answered directly, even when she repeats them. Why does Wayne not live with his young daughter? When this sunny girl is introduced and her name is announced as Sequoia – not just a hippy-dippy plant choice, but, pretentiously, the greatest of American trees – I had to stifle a giggle. Typical Baker, to invite us to laugh at her creations while being kind to them herself.

Running through a shopping mall with Sequoia is about as much animated childlike fun as Lacy gets. She may be getting a friend at last, somebody to talk in backchat to. Usually she is hauled off to pursuits she has no appetite for: the opening scene shows her slipping out at night at summer camp to phone Janet and demand to be taken home. Janet is generally patient, permissive even, still waiting for Lacy to move on from sharing her bed with her, but the relationship between them seems fragile.

When Wayne’s odd behaviour has progressed from his being poleaxed by migraines to kneeling outside in the dark, we soon see an intertitle: END WAYNE, and move on to Regina (Sophie Okonedo, pictured below with Nicholson), a long-lost friend of Janet’s and a leading light of the theatre group – aka cult – that Janet and Lacy have gone to see perform. Regina has just ended a relationship with the smooth-talking leader of the group, Avi (Elias Koteas), and is soon installed in Janet’s house. But the two women start to rub against each other when Regina expresses insights into Janet’s behaviour that Janet disputes. Then it’s END REGINA and enter AVI.

Lacy looks on, mostly wordless until she is suddenly moved to become loud and demanding because she doesn’t understand the grown-ups’ behaviour. Ziegler’s face, which the camera often stares back at, is a minefield of eyebrow flickers and eye-rolls, communicating that she is amused/bored/mystified by what she is watching.

Lacy looks on, mostly wordless until she is suddenly moved to become loud and demanding because she doesn’t understand the grown-ups’ behaviour. Ziegler’s face, which the camera often stares back at, is a minefield of eyebrow flickers and eye-rolls, communicating that she is amused/bored/mystified by what she is watching.

Nicholson gives an effortlessly spot-on performance too as a woman who knows she can get what she wants from men, but wonders whether she actually wants it. On a forest walk with Lacy she reveals the nub of her self-doubt in the time it takes her to cross the screen, as she rehearses a stricture of Avi‘s, trying out different terms for it as a way to memorise and personalise it. The joke is that Avi’s stricture is for his group to put truth before ego, presumably in line with his dodgy mantra that they should aim for “radical impersonal love". (I don’t think we are talking Plato here, judging by Avi’s hit rate with women.)

As usual, Baker leads you into the heart of a situation but then leaves you to make your own decision about it. She provides the ingredients for an explosion but doesn’t make it go off onstage, only in your mind, which may be why some find her work slow and uneventful. In this film, too, she leaves you at the crucial point where Lacy is beginning to discuss her sexuality with her mother. Is Janet’s parenting sound? Is her liberal stance towards her child beneficial? When Lacy finds a curious doll at her piano teacher's dressed as Red Riding Hood, which turns upside down to become a granny, then can turn again to reveal the wolf inside her head, you suspect this is a comment on Janet's parenting too.

Baker’s move to film is impressive. She has sidestepped a key pitfall for stage directors of using too much dialogue and thinking all the mise-en-scène has to be arty and inventive. Her DP, Maria von Hausswolff, supplies some lovely shots, often of little characters seen from a distance in a big landscape. But Baker combines those with a clever sound design by Paul Hsu that can amplify what the characters are saying clearly even from a distance, or conversely muffle a conversation Lacy is trying to eavesdrop on from one floor up, to represent her sense of exclusion. No detail seems extraneous. Best of all is a triptych created in the bathroom’s three-panelled mirror where Janet is trying to explain to Lacy what a cult is, and we see three versions of the top half of Lacy’s face, a striking reflection of her confused struggle to see and be seen.

In the final stretch, a man at the barn dance asks Lacy, sitting alone watching the adults whirl dynamically to a caller’s instructions, would she like to dance? Well, would she? Baker gives us an intense close-up of her face as a teasing roadmap to an answer.

Add comment