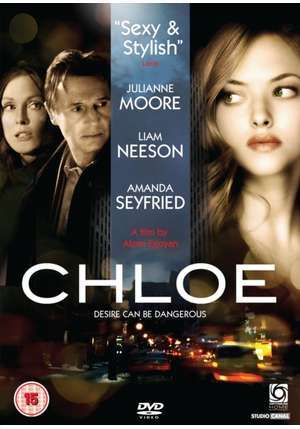

Julianne Moore (b. 1960) is a true rarity. It’s not just that her hair flames like no other star since Katharine Hepburn. Or that alone of her generation she seems impervious to middle age’s indignities. There’s something else. Having worked with dinosaurs in The Lost World and a cannibal in Hannibal, she is mainstream enough to be considered a genuine leading lady. But much of her most eye-catching work, often written for her by indie directors like Todd Haynes and Paul Thomas Anderson, is fiercely extreme in spirit. Pornography, incest, erotica of various hues – hers would be bargepole roles for most actresses. But Moore isn’t most actresses. She is the closest the English language has to a French actress. Hence Chloe.

In an adaptation of Anne Fontaine’s Parisian three-hander Nathalie (2003), Moore plays a Toronto gynaecologist who, suspecting her husband (Liam Neeson) of infidelity, commissions a prostitute (Amanda Seyfried) to seduce him and report back: this is Catherine’s creative way of looking for clues which might explain why the spark has exited the bedroom. It’s a thoroughly French scenario, given a cool Canadian twist by Atom Egoyan, but also another erotically charged role in which Moore once again goes the extra mile. Previous instances range from Anderson’s Boogie Nights (pictured below) to Savage Grace (2007), an Oedipal saga based on a true story, in which she played a mother incestuously obsessed with her son.

In film after film, she has perfected the filigree nuance, in the subtle gradations of period sensitivity. See her alcoholic divorcee in A Single Man, or her suicidal mother in The Hours. See above all what is probably her finest performance: in Far from Heaven (2002), Todd Haynes’s pastiche of the Fifties weepie, Moore matchlessly embodied a fey housewifely brittleness. It makes sense therefore that Moore should have landed a role once played by Fanny Ardant. The most French of American actresses talks to theartsdesk.

In film after film, she has perfected the filigree nuance, in the subtle gradations of period sensitivity. See her alcoholic divorcee in A Single Man, or her suicidal mother in The Hours. See above all what is probably her finest performance: in Far from Heaven (2002), Todd Haynes’s pastiche of the Fifties weepie, Moore matchlessly embodied a fey housewifely brittleness. It makes sense therefore that Moore should have landed a role once played by Fanny Ardant. The most French of American actresses talks to theartsdesk.

JASPER REES: To begin with Chloe, did you watch Nathalie, the French film on which it was based?

JULIANNE MOORE: No I didn’t. I didn’t know of it before they told me it’s based on a French film and I didn’t watch it deliberately because I’m incredibly suggestible and I didn’t want to be in a place where I felt like I was doing Fanny Ardant or something. So I actually want to see it now. It’s one of those things like, OK, I’m ready to see Nathalie. Everybody said, “You can see it or not see it.” It takes the idea of the French film and goes that much farther.

In a way it’s good not to have seen it so you don’t know about the twist. But it does go in a different direction. When you read in the script that the women develop their own relationship which in Nathalie they very specifically avoid – there’s a moment where you think they might go down that road – what was your initial response?

It made me nervous. Erin Cressida Wilson is a great writer and she writes stuff that is very explicit emotionally. It’s tricky stuff to do. When Atom and I had our meeting, I felt like had this come to me with somebody other than Atom attached as a director it would have really given me pause. But I know what kind of movies he makes and how he’s going to present something. Everything is presented in a very human, very plausible light. He doesn’t stand outside his material and kind of comment on it. Honestly, unless you’re in Catherine’s decisions every step of the way, if you allow her to get out of it, then it can be - yeah, it can be prurient or salacious or some kind of whole other thing. I think what you want with this kind of material is to stay inside all of her choices, so that she seems to be taking one kind of small logical step and you understand why. At the end of that second meeting she says, “You know what? I’m going to take this one step further,” so when you finally get to the part when they’re finally together that way, it’s like that thing of tragedy seeming inevitable. You don't want something to happen but there seems to be an inevitability to it that the character is just heading in that direction. So I very much felt reading it that in Atom’s hands – and we discussed it at length – how to make sure that that happened.

It made me nervous. Erin Cressida Wilson is a great writer and she writes stuff that is very explicit emotionally. It’s tricky stuff to do. When Atom and I had our meeting, I felt like had this come to me with somebody other than Atom attached as a director it would have really given me pause. But I know what kind of movies he makes and how he’s going to present something. Everything is presented in a very human, very plausible light. He doesn’t stand outside his material and kind of comment on it. Honestly, unless you’re in Catherine’s decisions every step of the way, if you allow her to get out of it, then it can be - yeah, it can be prurient or salacious or some kind of whole other thing. I think what you want with this kind of material is to stay inside all of her choices, so that she seems to be taking one kind of small logical step and you understand why. At the end of that second meeting she says, “You know what? I’m going to take this one step further,” so when you finally get to the part when they’re finally together that way, it’s like that thing of tragedy seeming inevitable. You don't want something to happen but there seems to be an inevitability to it that the character is just heading in that direction. So I very much felt reading it that in Atom’s hands – and we discussed it at length – how to make sure that that happened.

And what were the nuts and bolts?

I don’t know. It’s not like we drew up a series of tenets that we walked away with. We talked about the intention a lot and what the character’s emotional progression was, where she was going in each meeting, where she was going with something. The really interesting thing to me is that you are asked to identify with Catherine’s perspective, with her dilemma, with her fragility, with her lack of confidence, and she uses this girl as a conduit as a way to reach back to her husband. You’re with her and you see this big dénouement and they get back together and thank goodness, problem solved, and then the audience realises that what she complains about, about being unseen, about being invisible, is what she’s just done to another human being, at great cost. Great cost. So that’s one of the great things about Atom’s film-making. He allows that to happen. He sees the duality in this one person.

That makes sense. But you have to do the scene in which she goes to bed with the younger woman. In the hands of another director it would have given you pause but it is plainly the manifestation of a very corny male fantasy. [She laughs]. You must have been aware of that.

Oh gosh, yes of course.

Was there a need to ensure that you weren’t playing in the hands of male fantasists. In the end that scene has to be filmed.

Oh yeah, but it was all very deliberately staged, it was rehearsed, we watched playback, we were able to adjust things. One of the things that was interesting to me that we did was that in the scene I won’t look at her. The line that Catherine is drawing is about sheer fantasy, it’s about how do I get back to him, so she says, “Show me, how does he do it?” And then you see the same thing happen to her with the boy later on. The idea to subvert a desire I think is interesting. Obviously there’s something inherently dangerous about doing a scene like that but when you’re trying to keep it in line with the through-line of the characters and Atom certainly did that.

You’re very free with nude scenes. A lot of actresses don’t want to go there. Do you know what it is in you that feels able to do that kind of work?

It’s not like I ever intend to. I never do. It’s not like I say, “This is my intention with this film.” You know, there are times when I feel like it’s part of the movie and there are times when I feel it’s absolutely not necessary at all. I think it’s happened a lot of times because I’m involved in things that are love stories. Atom did say this at one point. “This is something that we do. Human beings do this.” So if you’re making a movie that’s about this kind of intimacy that that’s part of it. But sometimes it’s not necessary at all and you don’t do it. There was a movie I made called Savage Grace (Moore pictured below with Eddie Redmayne). My character had some nudity in it and I said to Tom [Kalin, the director], “I’m not doing it.” I said, “It’s really not right for this. If we bring the audience there it’s going to go to a whole different place.” And I felt like I was really right about it.

Did he take that on the chin?

Did he take that on the chin?

That means, is it OK? He totally did. I think it was right.

I think the most exposed you’ve been is in Far from Heaven.

Right.

Which was entirely clothed.

And pregnant.

Oh really? Did that make a difference to your performance?

That I was pregnant? No. I don’t think so.

I was referring to raging hormones.

I was actually OK. It was my second trimester when generally you feel OK. The great thing for me was that it distracted me from my pregnancy because I was busy and I was really, really happy making the movie.

It didn’t make you more raw or exposed?

I don’t think so. I was pregnant in The Big Lebowski too. So you know...

How did you find that woman in Far from Heaven and paint her on the screen?

You know, I don’t mean to be disingenuous but it’s true. For me, if I can’t connect with it on the page... When I read it I feel like I can hear and when I can’t hear it I can’t do it. And Todd and I almost had a particular type of working relationship. It was the same with Safe. I read Safe and I thought, I know how this should go. I thought, this is the only way. Todd being in the agreement, we had a read through with Dennis Quaid one day. Because Todd had written it for me, it was like a great present, I said, “OK, Todd, before you talk about it, I want you to hear what I’m doing. Just tell me if this is what you mean.” And we were kind of in the same place. But I felt like it was very present on the page. Also with a film like Far from Heaven (pictured above), that kind of 1950s performance style is in our DNA in a way. Everybody grew up with these movies on television and that heightened melodramatic performance style. It’s very particular and it’s that real meld of emotion and form. Gesture and style, it’s a really exciting way to work when you have that sort of shape and the fact that he packed it with that much real emotion meant that it was a pleasure to do.

You know, I don’t mean to be disingenuous but it’s true. For me, if I can’t connect with it on the page... When I read it I feel like I can hear and when I can’t hear it I can’t do it. And Todd and I almost had a particular type of working relationship. It was the same with Safe. I read Safe and I thought, I know how this should go. I thought, this is the only way. Todd being in the agreement, we had a read through with Dennis Quaid one day. Because Todd had written it for me, it was like a great present, I said, “OK, Todd, before you talk about it, I want you to hear what I’m doing. Just tell me if this is what you mean.” And we were kind of in the same place. But I felt like it was very present on the page. Also with a film like Far from Heaven (pictured above), that kind of 1950s performance style is in our DNA in a way. Everybody grew up with these movies on television and that heightened melodramatic performance style. It’s very particular and it’s that real meld of emotion and form. Gesture and style, it’s a really exciting way to work when you have that sort of shape and the fact that he packed it with that much real emotion meant that it was a pleasure to do.

So when you did your demo did he say, “We’ll go with that?”

He was very happy. He was like “Yes! Yes!” So that was OK. But I think that’s the case with a lot of things. What you hope as an actor is that the sensation you’re getting from the script, the ideas that you have, are going to match the director’s, because if you’re very far apart obviously everybody is going to be very unhappy. And you want to be in sync with somebody stylistically and emotionally.

How many times has a script been written for you and reached the screen?

A couple of times. I think Paul wrote the Boogie Nights part and Magnolia I think with me in mind. Todd wrote Far From Heaven. Tom Ford said he wrote that little part in A Single Man (pictured below) with me in mind as well.

Do you know what they are thinking of in you?

Do you know what they are thinking of in you?

No. Bob Altman way always that way too. Bob was really specific with casting and you never knew what it was that he saw in you or what it was that he wanted. But he was specific in wanting you. Or maybe he just made you feel that way. That was the miracle of Bob Altman. You always felt like you were Bob’s choice. You were there because he decided that he wanted you. He was magnificent with actors that way. He made you feel like whatever you chose was the right thing. So I don’t know. I don't know what it is when people say they’ve written something for you or with you in mind. You never know precisely what they’re looking for and sometimes it’s good not to know. If you have your finger on it it might be too dead on or something. Sometimes you want to have some tension between what you think somebody wants and what you’re doing.

It might produce a more automated performance?

Or it might lead you in a direction you weren’t intending to go. If somebody said, “Hey, it’s this quality I’m looking for,” you go, “OK”, when sometimes it’s just better to see what it elicits in you.

'Shame on you!' Julianne Moore in Magnolia

You know the Tolstoyan idea of every unhappy family being unhappy in their own way? You’ve played a lot of unhappy woman in unhappy marriages. Is this another one in Chloe?

I don’t think it’s an unhappy marriage. I think it’s an unhappy time in a long relationship. I think there’s a difference. In Far from Heaven that’s a marriage that’s clearly not a marriage. He doesn’t want to be there with her. This is a marriage that has been a long term relationship. These are people that have really wanted to be together, that have got together quite passionately, that have had lives and jobs and family and distractions and they’re at a point where they have miscommunicated. And Catherine no longer feels that she is desirable to her husband. She thinks he’s having an affair, her confidence is eroding. But she loves him. All she wants is to connect with him again. I think that’s different from being in an unhappy marriage where you feel like you’re dying.

There is something about portraying unhappiness on screen.

Well, it’s dramatic, isn’t it! I think the way that Tolstoy said it, he didn’t write many novels about happy people because all happy people are alike. He’s basically saying, “Where’s the drama?” For me, a lot of my movies have been about domestic drama and of course that entails sometimes some unhappiness or some kind of a hardship or whatever. And really if you’re going to do actual human drama it’s going to be probably about relationships rather than being just plot-driven. Most of my movies haven’t been about...

Dinosaurs?

Yeah. Getting to the top of the mountain. Getting from point A to point B or whatever. Although I’ve had the occasional dinosaur movie. But for the most part they are about relationships.

And that’s where you want to be?

I think so. I think that’s what defines us – our lives and our relationships with other people. That’s what makes us human. That’s what compels us again and again and again. Even if it is a drama about getting to the top of the mountain, generally when you explore that drama the person wants to get to the top of the mountain because of so and so, because there is some kind of relationship meaning they are extracting from it.

Who is the happiest person you’ve ever played?

I don’t know. I don’t know if I can remember all of them.

It’s got to be the woman in Cookie’s Fortune.

Oh, she’s pretty happy but she’s also kind of... She’s very happy at the end. You don't actually know if she’s happy when her sister goes to jail.

She’s also happy because she’s stupid.

I was going to say she also might have some brain damage, that character. I like that character. My son was six months old at the time and it was my first job back so a lot of my gestures were things that he did as a baby, that I would do and Bob would really like and would make him laugh.

But often you don’t get to make people laugh.

No, I have a few times. Not enough. That’s really my favourite stuff to watch. I love Arrested Development. I’m obsessed with 30 Rock. I like any kind of situational comedy. It breaks my heart that I’m not going to be in it but I’m not.

Are there any circumstances in which you would accept an offer to be in a gross-out comedy?

I think just about any. It depends.

Would you have had the semen hair gel in your hair?

Oh sure! I thought she was great in that movie. Cameron Diaz is somebody whose work I admire tremendously and I think she’s absolutely charming and really funny. I really enjoy watching all that kind of stuff.

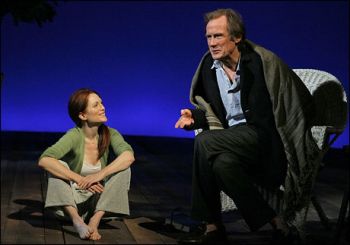

When you did theatre in New York, The Vertical Hour by David Hare (Moore pictured below with Bill Nighy), did that in any way inform the way you went back to screen acting afterwards?

I don’t know that it did. It’s a very different medium. Every actor will tell you that. I think it definitely informed my ideas about the theatre and about Broadway in particular. I absolutely love Bill Nighy. We had a great time and I loved everybody involved in that production but for me, I did find it particularly difficult to do Broadway and I think there are people who really enjoy that medium and it was not my favourite way to perform. It just wasn't.

Was it about putting the big star on a platter?

Was it about putting the big star on a platter?

It’s the performance aspect of it. When I do theatre I like it to be smaller, I like the audience to be closer, I like it to be less presentational. I think the nature of that kind of theatre is that it is in that form so it is presentational. You have the audience here and the actors here. That to me is very, very different from screen acting where the proscenium is obviously dimensional, it’s always changing and stuff. But it was a very interesting experience, because I hadn’t had it. I didn't know what it was like to do Broadway until I did Broadway and I was like, “Oh, OK, it’s like that.” I think like all that stuff is important to try.

How long had you not acted onstage for?

It had been a while. It was certainly before my children were born. It’s very difficult to do when you have kids because the hours are fairly extreme. It’s very hard with kids. You can’t. Even in my home town. Eight shows a week, the weekends are shot, my daughter would sometimes come and sit in my dressing room all weekend long. Wednesdays you didn’t see them at all. I would pick them up from school and three hours later I’d have to go to work, so couldn’t put them to bed. That was a tough thing, until they get older, I think.

You’re famously a late starter in a number of areas. But when you got to film had you been primarily a stage actress before?

No. I’m a late starter but it was late to being famous really. I worked right out of college, and that’s all you ever want to do as an actor is work. I started in a soap opera, I did a lot of night-time television, I also worked in Off-Broadway and regional theatre. So I did mostly television and theatre mixed really until I was 29. And then 29-30, I started doing features and stuff. So it was kind of like that. So I came late to film. I was pretty lucky, I started working right away.

How Scottish do you feel?

Um, you know, half and half. It was important to my mother and because it was important to her it’s important to me. But she died very suddenly and she was only 68.

Did she retain her accent?

She didn’t. That was funny. She did for a really long time because when I was growing up people would always say, “Why does your mother talk so funny?” And she did. She had an accent for a very long time, until she was in her thirties. My mother was only 20 years older than I am so it wasn’t really gone until I was in my early teens. And then when her mother died, when she was 40, that was when she kind of lost it because she didn’t hear it any more. We came to Scotland when I was like 27 or 28 and her aunts were still alive then and said to her, “You’ve lost your accent.” She said, “No I haven’t.” And she couldn’t hear it. But she did lose it eventually.

You’ve got the colouring.

You’ve got the colouring.

I look just like her.

I’m sure it’s not on your list of favourite movies but when you were doing Jurassic Park (pictured right)...

I enjoyed myself tremendously.

But it’s not high art, is it? Is there a part of you that doesn’t really want to get involved in that kind of massively budgeted film?

Well, I don't know because I’ve also had really good fortune with some of those movies. I loved doing The Lost World with Steven [Spielberg] and then I had Hannibal with Ridley Scott. The big movies that I’ve done I’ve worked with directors that I’ve admired, and cast members. I’ve really enjoyed a different kind of experience. Like doing the Broadway play, you don't know what that experience is until you do it. It’s a slightly different medium too. I honestly have enjoyed the experiences that I’ve had but clearly just in terms of what I’ve been attracted to, I really like story, and I like really complicated story. Your choices end up leading down different directions.

In the end those big movies are not about character, or less about character.

Yeah, they’re more about events. But there’s nothing wrong with that either. In terms of entertainment there is a broad spectrum of stuff and people don't want to be fed a steady diet of anything. Really you want to have variety as a viewer and as an actor too. I think if you spend your career doing one thing solidly, people get burned out.

Add comment