The Dark Side of the Moon: A Counterblast | reviews, news & interviews

The Dark Side of the Moon: A Counterblast

The Dark Side of the Moon: A Counterblast

Was the revolutionary album really so great? A dissenter suggests not

In March 1973, John Lennon was 33. Elvis was 38. There was barely a musician, in the sense we understand it, over 40. No one with a mortgage – or hardly anyone – was into rock’n’roll. The Dark Side of the Moon changed all that. It made rock middle-aged.

Us-us-us and them...

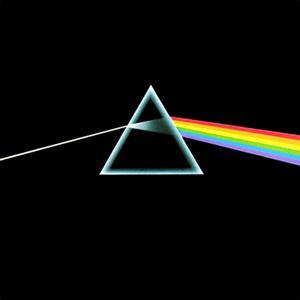

I remember going round to a friend’s after school to hear the long-awaited new Pink Floyd album just days after its release. And I equally well remember sitting there with the late afternoon sun flooding into his bedroom, the vinyl disc with its rainbow-prism label revolving on his cheap stereo, and thinking, "No!"

I feel almost jealous of myself for having been there, but actually it was boring

I was a 15-year-old in search of the far out, the experimental, the visionary. Probably I should have been into Can, Beefheart and Sun Ra, but in my suburban enclave I was barely aware they existed. Pink Floyd’s apparent isolation from the mainstream – they didn’t release singles or play the PR game – fed my sense of them as the great Underground band. I’d drunk in Atom Heart Mother and Meddle, thinking them hallucinatory and beautiful. From my limited perspective those albums had the advantage that they were more or less abstract: their messages – in that they had any – remained vague.

The problem with the music I was now hearing, as tracks like “Home” and “Us and Them” rolled out of the little speakers, was that its meaning was all too painfully clear: “And after all we’re only ord-inary men.” The lyrics had the worthy clunkiness of lines written by your English teacher for some well-meaning school play. Elements of the beauty I had discerned in those earlier albums were present, but framing Roger Waters’ commonplace observation on consumerism and the pressures of modern life, they sounded merely pretty. The total aural effect was fatally innocuous. It was all too manicured, too pleasant, too close to what I thought of as straight people’s music, to TV themes, even The Carpenters. I can’t claim that I thought, This is NOT rock’n’roll, because I hadn’t yet grasped rock’n’roll as a philosophical concept, but it was manifestly NOT rock’n’roll.

The following autumn, I saw The Dark Side of the Moon performed live at the Rainbow Theatre in Finsbury Park at a benefit for Robert Wyatt with support from Soft Machine. Writing that I feel almost jealous of myself for having been there, but actually it was boring. The great magnum opus was trundled out with an oddly grudging air of “this is a masterpiece, take it or leave it”. We sat there, listened to the album played exactly as it was on the record, then we went home. Like the whole Dark Side of the Moon phenomenon, the experience was fundamentally passive.

By this time every uncool kid, not only in my school, but in the entire world was getting into The Dark Side of the Moon, just as they would later get into Tubular Bells. Every accountant and under-manager in the country of less than advanced years was realising there was something in this “progressive music”. I’m probably making my teenage self sound an irksomely snobbish little upstart who needed his bottom smacked. Probably I was. Yet while I doubt I’d now hold to one thing I believed when I was 15, my view on The Dark Side of the Moon hasn’t shifted one iota since that first hearing. I find it dull, ponderous, humourless. Its observations on the human condition are mundane. Its sense of a cosmic overview is bogus. Its message is admirable – if telling people what they already know can be considered admirable. While it was launched on the world as the anti-materialist tirade of a bunch of freaks, its musical language is insidiously corporate, as befits a band that went on to become an endlessly self-perpetuating money-making machine. “Money, it’s a gas.” Yes, it is, David.

By this time every uncool kid, not only in my school, but in the entire world was getting into The Dark Side of the Moon, just as they would later get into Tubular Bells. Every accountant and under-manager in the country of less than advanced years was realising there was something in this “progressive music”. I’m probably making my teenage self sound an irksomely snobbish little upstart who needed his bottom smacked. Probably I was. Yet while I doubt I’d now hold to one thing I believed when I was 15, my view on The Dark Side of the Moon hasn’t shifted one iota since that first hearing. I find it dull, ponderous, humourless. Its observations on the human condition are mundane. Its sense of a cosmic overview is bogus. Its message is admirable – if telling people what they already know can be considered admirable. While it was launched on the world as the anti-materialist tirade of a bunch of freaks, its musical language is insidiously corporate, as befits a band that went on to become an endlessly self-perpetuating money-making machine. “Money, it’s a gas.” Yes, it is, David.

The aural quality of The Dark Side of the Moon is sterile, soothing, comfortably numbing – music to be listened to while recovering in hospital. And in case you’re wondering, “Money” is not funky. I’m not one of those people who high-handedly dismiss the interests of suburbia – that’s where I come from. But while The Dark Side of the Moon purports to criticise the Rat Race and the nine-to-five world, it is in fact a palliative rather than a challenge to that way of life – and a very lucrative one. You buy the album, go to the gig, then you go back to your semi-detached house and your spliff, mug of Ovaltine or whatever it is you’re into...

Black-black-black-and-blu...

The Dark Side of the Moon conception of rock as a complacent, soporific consumer experience, in which the creator remains remote in a world of mansions and private jets, became eventually one of the stimulants for punk. Yet while John Lydon wore a handmade “I hate Pink Floyd” t-shirt at Sex Pistols gigs, he claimed recently that the joke was he really liked the band all along. When I went to Marrakesh recently a local DJ told me with a chuckle that he loved Pink Floyd. “But everybody loves Pink Floyd.” So now it is just me.

Down-down-down-ou...

No!

Read about The Dark Side of the Moon on theartsdesk

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Emily A. Sprague realises a Japanese dream on 'Cloud Time'

A set of live improvisations that drift in and out of real beauty

Emily A. Sprague realises a Japanese dream on 'Cloud Time'

A set of live improvisations that drift in and out of real beauty

Trio Da Kali, Milton Court review - Mali masters make the ancient new

Three supreme musicians from Bamako in transcendent mood

Trio Da Kali, Milton Court review - Mali masters make the ancient new

Three supreme musicians from Bamako in transcendent mood

Hollie Cook's 'Shy Girl' isn't heavyweight but has a summery reggae lilt

Tropical-tinted downtempo pop that's likeable if uneventful

Hollie Cook's 'Shy Girl' isn't heavyweight but has a summery reggae lilt

Tropical-tinted downtempo pop that's likeable if uneventful

Pop Will Eat Itself's 'Delete Everything' is noisy but patchy

Despite unlovely production, the Eighties/Nineties unit retain rowdy ebullience

Pop Will Eat Itself's 'Delete Everything' is noisy but patchy

Despite unlovely production, the Eighties/Nineties unit retain rowdy ebullience

Music Reissues Weekly: The Earlies - These Were The Earlies

Lancashire and Texas unite to fashion a 2004 landmark of modern psychedelia

Music Reissues Weekly: The Earlies - These Were The Earlies

Lancashire and Texas unite to fashion a 2004 landmark of modern psychedelia

Odd times and clunking lines in 'The Life of a Showgirl' for Taylor Swift

A record this weird should be more interesting, surely

Odd times and clunking lines in 'The Life of a Showgirl' for Taylor Swift

A record this weird should be more interesting, surely

Comments

I can understand why the