Virtuoso Violinists was an hour of unalloyed informative pleasure that toured televised highlights of great violinists playing great music. Its painless excursion into the western classical canon reminded us why the BBC is the NHS of culture, and we delighted here in a guide who proved as accomplished a presenter as she is a performer of genius.

Nicola Benedetti has an Italian name, a Scottish accent, and an utterly charming manner as she enthused, with immense knowledge, over a series of clips from 60 years of television broadcasts of the leading violinists of the day. She made no attempt to justify her selection, pared down from a wealth of possibilities: it was a highly personal choice, from violinists she admired to violinists who also influenced her own thinking, playing and musicianship. We were first introduced to her as a performer at the 2012 Last Night of the Proms (pictured below by Chris Christodoulou) with Bruch’s First Violin Concerto, fearless in her ability to communicate sheer enjoyment as well as unforced virtuosity.

It was surprising as always how ordinary genius can look

Benedetti is a leading light in the current dazzling young generation of superb musicians, who has built an international career after finishing the Yehudi Menuhin School. Another illustrious graduate there was the enfant terrible Nigel Kennedy, and she showed him first in young student guise, and then in a studio with a small orchestra in 1990 leading, of course, Vivaldi’s Four Seasons (Autumn); she generously and accurately pointed out that he has brought classical music to the ears of a huge, previously uninitiated population.

While the chosen performances were as fresh as yesterday, the styles of presentation have changed: early black and white footage had a kind of formality that has been slowly eroded. Several of the recordings took place in isolation – not concerts, but performances solely for the camera set in unspecified locations that imitated, or perhaps were, drawing rooms in stately homes. The greater part, though, were from the Proms, in colour, with the bust of Henry Wood a genially dignified presence in the background.

We started with a 1957 black and white clip of Nathan Milstein, demonstrating what Benedetti described as his pure, direct and silvery tone with a Mozart Adagio in D minor. In dashing contrast this was followed by the young Maxim Vengerov playing Bazzini’s fiendishly difficult Dance of the Goblins as an encore at a 1999 Prom; his fingers moved so quickly they were hardly in focus, dazzle was all, and his palpable enjoyment reached levels which could be almost described as ecstatic.

We started with a 1957 black and white clip of Nathan Milstein, demonstrating what Benedetti described as his pure, direct and silvery tone with a Mozart Adagio in D minor. In dashing contrast this was followed by the young Maxim Vengerov playing Bazzini’s fiendishly difficult Dance of the Goblins as an encore at a 1999 Prom; his fingers moved so quickly they were hardly in focus, dazzle was all, and his palpable enjoyment reached levels which could be almost described as ecstatic.

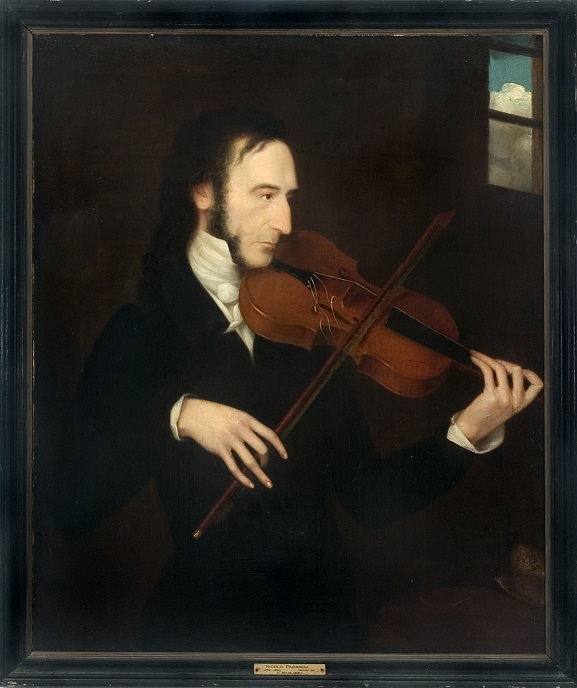

When not performing herself Benedetti linked us from performance to performance, presenting from the museum at the Royal Academy of Music, where we were also introduced to that virtuoso of all virtuosi, Niccolò Paganini, who played with such vehemence that the strings of his violin were constantly breaking, as shown in the contemporary portrait at the RAM (pictured below left, signed "D. Maclise", 1831, courtesy Dover Museum). The other great composer-virtuoso, Saraste, also appeared: between the two of them they changed the popular notion of the violin, bringing the performer to as much prominence as the composer.

One of the great advantages of solo violinists for the audience is that, unlike the great pianists who can only be seen sideways on, their hands on the keyboard visible to just half the audience, the violinists are visible full-face and full-handed. Virtuoso Violinists enhanced this with close-ups of amazingly expressive, even agonised facial expressions – only a handful retained an eerie solemnity – and detail of the elaborate dance of the fingers on the strings, the subtle complications of bowing. Benedetti herself demonstrated left-handed pizzicato, upbow staccato and ricochet, and then showed such techniques in action in the music-making of her chosen stars. Musicians are athletes as well as artists; the necessary physical stamina is prodigious.

She told us that the personality of the musician was always imposed by violinists not only on their performance but on their instrument, too. The Russian Mischa Elman performed a piece by Kreisler (another composer-violinist) in a clip from 1962: he had a six-decade career, sold over two million records, and, said Benedetti, played in such a way that you always felt warmly embraced – he just made his audience feel good. Gidon Kremer was an expressive sight, slightly clown-like in appearance, playing Leonard Bernstein’s Serenade at the Barbican in 1986 conducted by the composer himself; they turned to one another with vivid body language. In a different sense, a radio broadcast told us how Yehudi Menuhin’s wartime concerts raised the country’s morale with classics such as the Brahms violin concerto, and Benedetti reminisced about how much his presence and example had meant at the music school which bears his name.

She told us that the personality of the musician was always imposed by violinists not only on their performance but on their instrument, too. The Russian Mischa Elman performed a piece by Kreisler (another composer-violinist) in a clip from 1962: he had a six-decade career, sold over two million records, and, said Benedetti, played in such a way that you always felt warmly embraced – he just made his audience feel good. Gidon Kremer was an expressive sight, slightly clown-like in appearance, playing Leonard Bernstein’s Serenade at the Barbican in 1986 conducted by the composer himself; they turned to one another with vivid body language. In a different sense, a radio broadcast told us how Yehudi Menuhin’s wartime concerts raised the country’s morale with classics such as the Brahms violin concerto, and Benedetti reminisced about how much his presence and example had meant at the music school which bears his name.

Finally we saw her own top violinist, the Russian genius David Oistrakh, slightly plump, even pudgy, physically unprepossessing, sweat pouring down his face as he played Brahms in a 1958 film; and the sublime moment when Oistrakh and Menuhin played together in Bach’s Double Violin Concerto in 1962. It was surprising as always how ordinary genius can look, as Benedetti more than convincingly recounted, and showed us Oistrakh’s integrity, quality and the transcendent beauty of his playing.

This remarkable compilation should enhance anyone’s understanding and appreciation the next time live, or broadcast, music is on the agenda. One flaw: we were rarely told details of location, nor were the orchestras and conductors always identified; no piano accompanists, themselves outstanding musicians, were named. Otherwise the producer and director, Helen Mansfield and Mark Cooper, gave us both an entrancing programme and a superb guide.

Add comment