Blu-ray: Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer | reviews, news & interviews

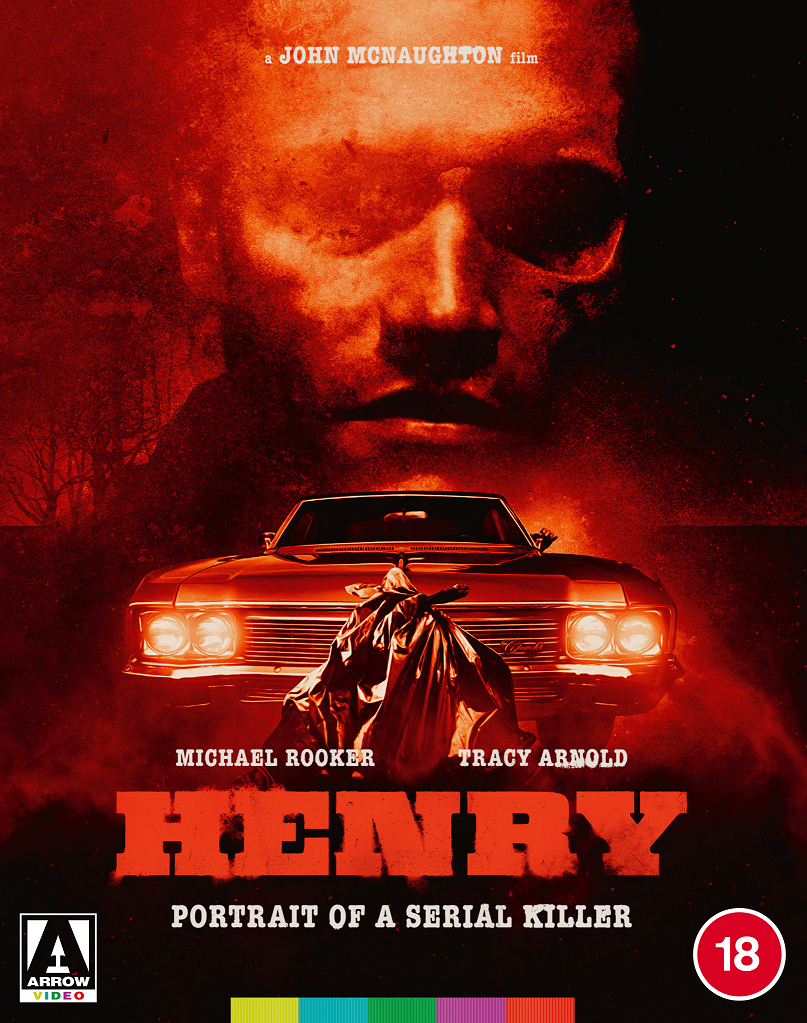

Blu-ray: Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer

Blu-ray: Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer

Viscerally uncomfortable genre landmark shows a mundane murderer's daily rounds

The Driller Killer, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer form a self-descriptive yet misunderstood trinity in American cinema’s sordid underground. Originally subtitled Sympathy for the Devil, Henry modernised the serial killer as protagonist, minus Hopkins' later suave intellect as Lecter, or Dexter’s benign foibles.

Debutant director John McNaughton begins with a close-up of a beautiful woman’s face, then pulls back to contemplate her body in blood-splashed grass, one of several aestheticized tableaus showing a slaughter pandemic. The sound design’s synths and muffled screams pile on eerie artifice uncommon in an exploitation pic. Part-time pest controller Henry is responsible, though, like McNaughton’s real life model Henry Lee Lucas, he may fantasise his mayhem’s extent; selecting a female victim, his battered green car glides in predatory, daylight pursuit. Back home in the dank, cramped apartment he shares with Otis (Tom Towles, styled like a sleazier Warren Oates with comb-over and shit-eating grin), Otis’s perky sister Becky (Tracy Arnold, pictured below with Towles and Rooker) seeks shelter from an abusive relationship. Hulking, brooding Henry seems a relative romantic knight down here in the grime, even as he includes Otis in his night-creeping sprees.

As the sociological title suggests, this is mostly a serial killer’s life between killings. Arrow’s 4K restoration just makes the film’s Chicago more grey and faded, its 1985 shoot recording suburbs leached of life. Henry and Otis seem natural manifestations of this environment, with Arnold’s Becky the blithe spark in their vicious midst. The film isn’t misogynist but the world is, as Henry explains to Otis that killers of disposable women are never caught.

As the sociological title suggests, this is mostly a serial killer’s life between killings. Arrow’s 4K restoration just makes the film’s Chicago more grey and faded, its 1985 shoot recording suburbs leached of life. Henry and Otis seem natural manifestations of this environment, with Arnold’s Becky the blithe spark in their vicious midst. The film isn’t misogynist but the world is, as Henry explains to Otis that killers of disposable women are never caught.

McNaughton drew collaborators from Chicago’s wild Organic Theater, including Arnold, Towles and Richard Fine, who talks of “the Aristotelian unities” in the Extras, and honed McNaughton’s ideas into a screenplay. Told they had to “make something with blood in it”, Fine “really wasn’t into making something for everybody”, instead writing “a character study that’s about horrific deeds”, with deadpan dialogue like Pinter in the grindhouse. He didn’t talk down to or judge Henry. As McNaughton says of these sadists, “they’re nonetheless human beings”.

I clearly remember how it felt to see Henry in a New York cinema when it crawled on screen in 1990, with its soiled extremity and radical genre intelligence. Very like The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, it’s disconcerting how that gruelling shock has dissipated with time, revealing dark wit, mostly in Henry and Otis’s dumb and dumber, dangerous double-act. Henry tips over the edge with a cinecamera recording of a home invasion in which Henry and Otis messily murder a terrified family, Otis molesting the mum even after she’s dead. McNaughton begins suddenly, the video grain grubbily, upsettingly real, then pulls back to the footage’s auteurs, Henry and Otis, as they relish the coup de grace over a beer, in slow-motion. “Play it again,” goes horny Otis. This scene still distinguishes Henry, dragging the viewer into visceral discomfort, even as McNaughton’s message on real and Hollywood horror is plain. Michael Haneke’s Funny Games (1997) was more meta about audience implication in screen violence, and Justin Kurzel’s Snowtown (2011) went further in its realistic depiction of a serial killer in a depressed society, its delayed, verité violence truly harrowing. But McNaughton’s tone has its own, relentless integrity.

Henry tips over the edge with a cinecamera recording of a home invasion in which Henry and Otis messily murder a terrified family, Otis molesting the mum even after she’s dead. McNaughton begins suddenly, the video grain grubbily, upsettingly real, then pulls back to the footage’s auteurs, Henry and Otis, as they relish the coup de grace over a beer, in slow-motion. “Play it again,” goes horny Otis. This scene still distinguishes Henry, dragging the viewer into visceral discomfort, even as McNaughton’s message on real and Hollywood horror is plain. Michael Haneke’s Funny Games (1997) was more meta about audience implication in screen violence, and Justin Kurzel’s Snowtown (2011) went further in its realistic depiction of a serial killer in a depressed society, its delayed, verité violence truly harrowing. But McNaughton’s tone has its own, relentless integrity.

Only the director’s gleefully sleazy erotic noir Wild Things (1998) made a subsequent impact, but lusty pulp remake Girls in Prison (1994), perverse crime character piece Mad Dog and Glory (1993, with De Niro, Bill Murray and Uma Thurman) and the twisted bank-robbing lovers in Normal Life (1996) show fulfilled, sly genre talent. As he protests in the Extras: “I was an art student.”

Those copious Extras, many on previous releases, include a new McNaughton commentary, deleted scenes (more corpse tableaus, from the golf course to roadside bin-bags), the screenplay, a making of doc, In Defence of Henry, with documentarist Errol Morris especially insightful, a new doc on camera-wielding killers, and forensic histories of Henry’s transatlantic censorship struggles.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

London Film Festival - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

London Film Festival - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

theartsdesk Q&A: Idris Elba on playing a US President faced with a missile crisis in 'A House of Dynamite'

The star talks about Presidential decision-making when millions of lives are imperilled

theartsdesk Q&A: Idris Elba on playing a US President faced with a missile crisis in 'A House of Dynamite'

The star talks about Presidential decision-making when millions of lives are imperilled

Urchin review - superb homeless drama

Frank Dillane gives a star-making turn in Harris Dickinson’s impressive directorial debut

Urchin review - superb homeless drama

Frank Dillane gives a star-making turn in Harris Dickinson’s impressive directorial debut

Mr Blake at Your Service review - John Malkovich in unlikely role as an English butler

Weird comedy directed by novelist Gilles Legardinier

Mr Blake at Your Service review - John Malkovich in unlikely role as an English butler

Weird comedy directed by novelist Gilles Legardinier

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight review - vivid adaptation of a memoir about a Rhodesian childhood

Embeth Davidtz delivers an impressive directing debut and an exceptional child star

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight review - vivid adaptation of a memoir about a Rhodesian childhood

Embeth Davidtz delivers an impressive directing debut and an exceptional child star

Add comment