Theatre is a strange dish. A recipe can be stacked with delicious ingredients, cooked to exacting standards, taste-test beautifully at the halfway mark, yet leave you not quite full, not exactly satisfied, disappointed that it didn’t come out quite as expected when plated up.

Autumn certainly looks good when you lay everything out on the kitchen table. A celebrated source novel from an award-winning writer (Ali Smith) adapted by Harry McDonald, fresh from his critical success, Foam, at the Finborough and Brexit, a hot button topic even eight years on, at its heart. Roll in a stellar cast, bake for 100 minutes at a simmering heat and…?

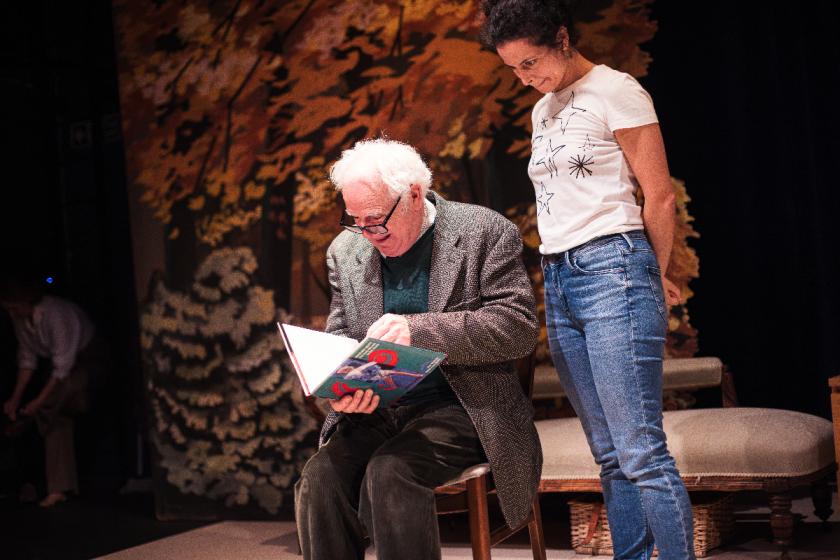

The play is at its best when Elisabeth (Rebecca Banatvala, pictured below) is at the heart of the action. We first meet her as a mardy teen, Banatvala getting Elisabeth's stiff-backed, clenched-fist stubbornness and intrusive questioning just right. We sense that she’s already outgrowing her mother (Sophie Ward) whom she can read like a book (and does Elisabeth read books!) and needs the father-figure missing from her life. With a twinkle in his eye and the key to unlock Elisabeth’s burgeoning imagination in his teasing conversation, 70-something Daniel Gluck (Gary Lilburn) befriends the lonely teen – game, as always, seeing game amongst intelligent people regardless of age, gender or history. The time frame slips backwards and forwards from the 1990s to 2016 as we see Elisabeth broker her bright inquisitive nature into a career – if a young academic can ever be said to have such a thing these days – as an Art History lecturer in London (good luck with that if it’s at Goldsmiths). En route, she encounters a country sliding into pettiness, repeatedly frustrated by a succession of jobsworths, all played with just enough comic exaggeration by Nancy Crane. Sure enough, that small-minded streak in the British, okay, English, character that has always been there, curdles under the stirring of mendacious journalism and deceitful politics into the referendum vote. She witnesses a growing anti-foreigner sentiment that is emboldened and shameless, the ‘s’ in the middle of her name, once exotic, but now a matter for comment and suspicion.

The time frame slips backwards and forwards from the 1990s to 2016 as we see Elisabeth broker her bright inquisitive nature into a career – if a young academic can ever be said to have such a thing these days – as an Art History lecturer in London (good luck with that if it’s at Goldsmiths). En route, she encounters a country sliding into pettiness, repeatedly frustrated by a succession of jobsworths, all played with just enough comic exaggeration by Nancy Crane. Sure enough, that small-minded streak in the British, okay, English, character that has always been there, curdles under the stirring of mendacious journalism and deceitful politics into the referendum vote. She witnesses a growing anti-foreigner sentiment that is emboldened and shameless, the ‘s’ in the middle of her name, once exotic, but now a matter for comment and suspicion.

Those attitudes contrast with the charm and decency of her now aged friend, Mr Gluck, a Holocaust survivor who keeps its horrors from her, a cultured man who wears his learning lightly but never misses a chance to encourage her. She pays him back by reading A Tale of Two Cities aloud to his sleeping form in the rest home, echoing how he has set her free to live the life she leads, as Sydney Carton famously did for Charles Darnay.

So far so good, but the play loses focus in its last half hour, introducing surreal scenes involving both Christine Keeler and the undeservedly forgotten, doomed collagist, Pauline Boty, the only woman to penetrate Pop Art’s boys club. That takes attention away from the relationship between Elisabeth and Gluck that has driven so much of what went before, Martin Amis's rule that dreams should be avoided in fiction proved rather too well. That loss of momentum isn’t helped by Elisabeth’s mother finding late-in-life love with a female ex-child TV star and present day psychoanalyst, a plot development that appears to come from another story altogether.

If that confused and contrived conclusion spoils some of the super work undertaken earlier, so too does an unwillingness, perhaps born out of fidelity to the source, often described as the first post-Brexit novel, to embrace what we now know of the enervating impact of departing the EU on economic growth, political discourse and cultural vitality. Just because the current government maintains an omerta on such matters doesn’t mean director, Charlotte Vickers, has her hands tied. That she chooses to go for an all-through 100 minutes runtime does not help the cause, as an interval would have benefited the audience, offering us an opportunity to take stock of what we know of Elisabeth, the dreaming, comatose Mr Gluck and the drifting, lonely mother. It’s a contradiction, but the second half of the play feels both pedestrian and rushed, too much happening too slowly.

So after a cordon bleu of a starter and main course, a bland dessert leaves us with less to contemplate over a digestif than initially appeared to be the case. The wait continues for theatre to find its definitive statement on Brexit, as indeed might be said equally or film, television and literature.

Add comment