Over the past decade Krystian Zimerman and Sir Simon Rattle have created and evolved a performing idea of Brahms’s D minor piano concerto which is still remarkable for its considered weight and grimly imposing grandeur, Michelangelo’s Mosè in music.

As played at the Barbican in its latest appearance, hardly so refined as in Berlin but undeniably exciting, that idea of the concerto has attenuated and intensified, not quite towards self-parody but moving ever farther from the sense of a piece from 1858, written squarely if boldly in the tradition of Beethoven by a 25-year-old composer almost two decades before the effortfully final form of the First Symphony which fixed the image of Brahms the tragic poet in the minds of his public, and forever more. Zimerman and Rattle do not give us beardless Brahms (as he then was) but a man outside his time (as he saw himself anyway), raging away like the dying Oedipus at Colonus through the mouth, pen or stylus of the elderly Sophocles.

Contrasts are writ balefully large in the concerto’s massive first movement which does not so much hurtle as stalk towards its unconquerably violent climax and unrepentantly furious close. Zimerman takes rubato in his stride, Rattle handles it less naturally in his inward contemplation of the introduction’s second theme. The two are of one mind about a sound-image for the concerto if inevitably using their different instruments in their own ways, Zimerman rhythmically freer if hardly struck at any point by the impetuous spirit of improvisation which this paradigmatically Romantic lion of a piece might nurture in other, mostly younger pianists (though Arthur Rubinstein knew how to turn the corners as if encountering them for the first time).

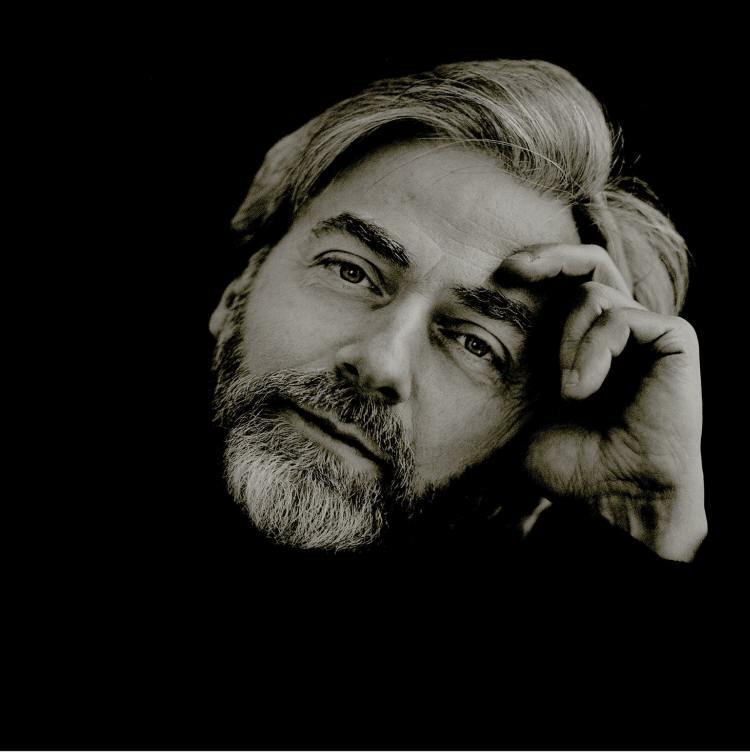

The Adagio could have brought some relief, not least in Zimerman’s dialogue with clarinettist Andrew Marriner; that it did not or would not may be attributed to Rattle’s cultivation of the longest possible singing line through a phrase, which he has found for himself during the years in Berlin, along with a bass anchor of tremendous weight yet never (unlike Karajan) overbalancing power. Zimerman himself (pictured left; photo: Kasskara/DG) pounded up and down the staircases to nowhere at the movement’s climax where his earlier, note-by-note weighting of touch and timbre might have lifted one of the concerto’s weakest passages.

The Adagio could have brought some relief, not least in Zimerman’s dialogue with clarinettist Andrew Marriner; that it did not or would not may be attributed to Rattle’s cultivation of the longest possible singing line through a phrase, which he has found for himself during the years in Berlin, along with a bass anchor of tremendous weight yet never (unlike Karajan) overbalancing power. Zimerman himself (pictured left; photo: Kasskara/DG) pounded up and down the staircases to nowhere at the movement’s climax where his earlier, note-by-note weighting of touch and timbre might have lifted one of the concerto’s weakest passages.

Such Hölderlin-heavy clouds of lacerating introspection naturally lifted for the finale, which fairly tripped along, convincing unto itself (at least until a ponderous summation before the rush to the double-bar) but lacking the balance of the Second Concerto’s similarly abrupt change of tack. When the LSO played it with Maurizio Pollini and Peter Eötvös five years ago, tempi were quicker but also more tightly knit, the concerto’s journey towards hard-won exaltation (or relief) more whole and continuous.

What followed was far more out of the ordinary: two of the four symphonic poems Dvořák wrote after the Ninth Symphony, returned to Europe, friends and family, relieved from teaching commitments and free to explore a synthesis of symphonic form and naturalistic narrative outside his bumpy career as an opera composer and through the ragingly fashionable genre of tone-poem. In The Wood Dove, Valentin Erben’s original poem describes a wife who poisons her husband and takes up with a younger lover. Stricken with conscience, she kills herself in what Dvořák (not Erben) fulfils as a redemptive act. The Golden Spinning Wheel is Rusalka with a happy ending, in which our medieval king finally gets his fantasy female after she’s been chopped to pieces and stitched back together: Doctor Coppelius meets Anna Nicole.

Rattle holds this music together as he does the more garrulously episodic movements of Mahler such as the Scherzo of the Fifth and finale of the Second, with lurid detail and episodically motivated contrasts that caught the LSO off-guard a few times. Connoisseurs of old Czech Philharmonic recordings (about the only other way to hear these pieces) may have pined for more of a pulse, but Dvořák must have had in mind an orchestra of soloists: playing with honeymoon-delight for their music director-to-be, the LSO fitted the bill, though they sounded more comfortable in two Slavonic Dances placed either side of The Golden Spinning-Wheel.

- Rattle and the LSO also appear at the Barbican on Sunday 5 July in Walton's First Symphony and Jonathan Dove's new opera for children The Monster in the Maze

Add comment