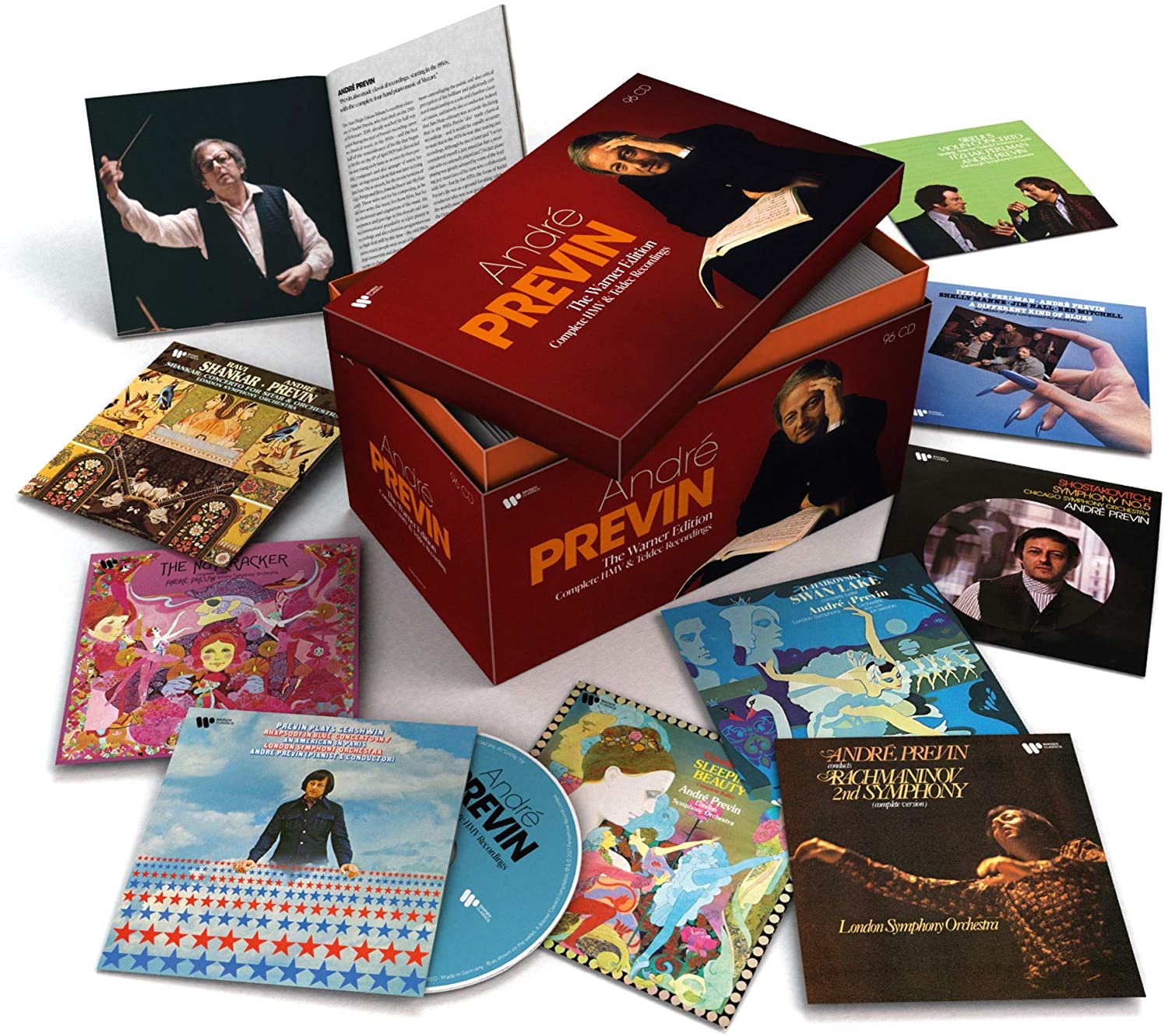

André Previn: The Warner Edition – Complete HMV & Teldec Recordings (Warner Classics)

André Previn: The Warner Edition – Complete HMV & Teldec Recordings (Warner Classics)

Flicking through this box set will provoke a Proustian rush if you’re of a certain age. These recordings were mostly made for EMI, though Warner Classics have wisely kept the LPs’ original sleeve art, reminding us of just how ubiquitous a presence André Previn once was in the UK. Many of these recordings were bestsellers, familiar to anyone who frequented record shops or public libraries in the 1970s or 1980s. A multilingual child prodigy, Previn began his musical career as a conductor and arranger for MGM studios in 1946 while he was still in high school, his family having arrived in the US from Germany eight years earlier. Previn’s rambling but witty memoir No Minor Chords is worth tracking down, giving a flavour of just how busy his early life was. He won four Academy Awards for his Hollywood work and pursued a parallel life as a jazz pianist, also managing to squeeze in conducting lessons with Pierre Monteux.

Previn’s relationship with the London Symphony Orchestra began in the mid-1960s and his tenure as Principal Conductor lasted from 1968-1979. An audio documentary assembled by Jon Tolansky is included as a bonus disc here and makes for entertaining listening; Previn’s appointment wasn’t unanimously welcomed, the relationship taking several years to bed in. The LSO’s management were taking a gamble in hiring a musician best known for his Hollywood work, though the choice was partly motivated by the parlous state of the orchestra’s finances, and the need to hire a big name to attract audiences. Naysayers were proved wrong; Previn was a phenomenal talent, and a charismatic front man, a brilliant, erudite populariser of classical music. I recently asked one of the LSO’s early 1970s horn section about the Previn era; he replied that Previn was “delightful to work with, wearing his polymath genius hat lightly and modest to a fault – he had authority without being authoritarian”. Several rehearsal sequences are included as extras and give us a sense of how sharp Previn’s ears were. Listen to the punchy, ingenious theme tune he composed for his long-running BBC TV series André Previn’s Music Night and you get a sense of his energy and wit.

Previn’s relationship with the London Symphony Orchestra began in the mid-1960s and his tenure as Principal Conductor lasted from 1968-1979. An audio documentary assembled by Jon Tolansky is included as a bonus disc here and makes for entertaining listening; Previn’s appointment wasn’t unanimously welcomed, the relationship taking several years to bed in. The LSO’s management were taking a gamble in hiring a musician best known for his Hollywood work, though the choice was partly motivated by the parlous state of the orchestra’s finances, and the need to hire a big name to attract audiences. Naysayers were proved wrong; Previn was a phenomenal talent, and a charismatic front man, a brilliant, erudite populariser of classical music. I recently asked one of the LSO’s early 1970s horn section about the Previn era; he replied that Previn was “delightful to work with, wearing his polymath genius hat lightly and modest to a fault – he had authority without being authoritarian”. Several rehearsal sequences are included as extras and give us a sense of how sharp Previn’s ears were. Listen to the punchy, ingenious theme tune he composed for his long-running BBC TV series André Previn’s Music Night and you get a sense of his energy and wit.

There’s masses to enjoy here, much of it freshly exhumed from the vaults. Several of the better-known performances don’t sound quite as good as you remember; Previn’s Carmina Burana is a tad ragged, and a famous complete recording of Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet isn’t as taut as Lorin Maazel’s Cleveland set, lushly enjoyable though it is. Russian music was a Previn speciality. His expansive 1973 take on Rachmaninov’s Symphony No. 2 is still a wowzer, often eclipsing his equally fine versions of the other symphonies and the Symphonic Dances. Prokofiev’s Alexander Nevsky has full-throated choral singing and a weighty, terrifying battle sequence. I’d not heard his superb, colourful recording of Prokofiev’s 5th Symphony before, and we get one of the best accounts of the complete Cinderella ballet committed to disc. Previn’s pioneering LSO recording of Shostakovich 8 still chills, and there’s an imposing version of No. 13, again with impressive chorus work.

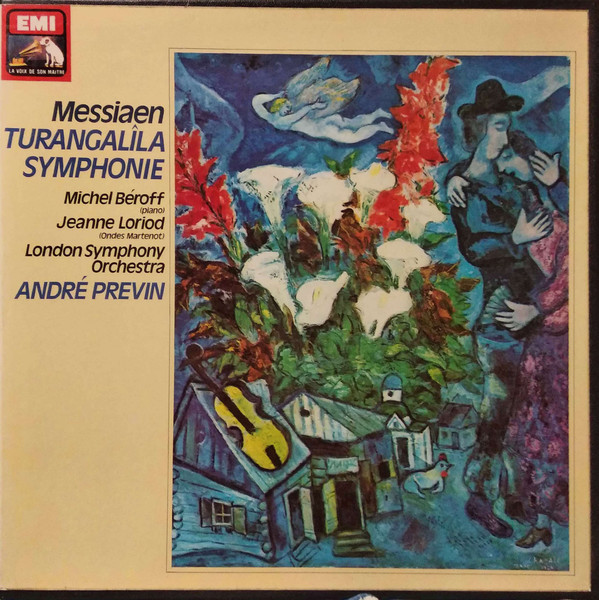

Britten’s Sinfonia da Requiem is pitch black here, though the disc of British music I’ve returned to most often couples Lambert’s The Rio Grande with Walton’s Symphony No. 2, both exhilarating. Itzhak Perlman is the soloist in Bartók's Violin Concerto No. 2, in a radiant performance that’s slipped through the cracks. Why is this work so infrequently performed? Still, if you’re after just one souvenir of the relationship between these players and their conductor, try their pioneering version of Messiaen’s Turangalîla-Symphonie from 1977, the recording only made after Previn had convinced a reluctant EMI to fund it. Has analogue engineering ever sounded so rich and detailed? Listen carefully through headphones and you can just hear one of the LSO’s percussionists stifling a giggle after a fulsome bass drum thwack at the close of “Turangalîla 2”. Some of the fruitier climaxes sound like Gershwin. It's astonishing.

Britten’s Sinfonia da Requiem is pitch black here, though the disc of British music I’ve returned to most often couples Lambert’s The Rio Grande with Walton’s Symphony No. 2, both exhilarating. Itzhak Perlman is the soloist in Bartók's Violin Concerto No. 2, in a radiant performance that’s slipped through the cracks. Why is this work so infrequently performed? Still, if you’re after just one souvenir of the relationship between these players and their conductor, try their pioneering version of Messiaen’s Turangalîla-Symphonie from 1977, the recording only made after Previn had convinced a reluctant EMI to fund it. Has analogue engineering ever sounded so rich and detailed? Listen carefully through headphones and you can just hear one of the LSO’s percussionists stifling a giggle after a fulsome bass drum thwack at the close of “Turangalîla 2”. Some of the fruitier climaxes sound like Gershwin. It's astonishing.

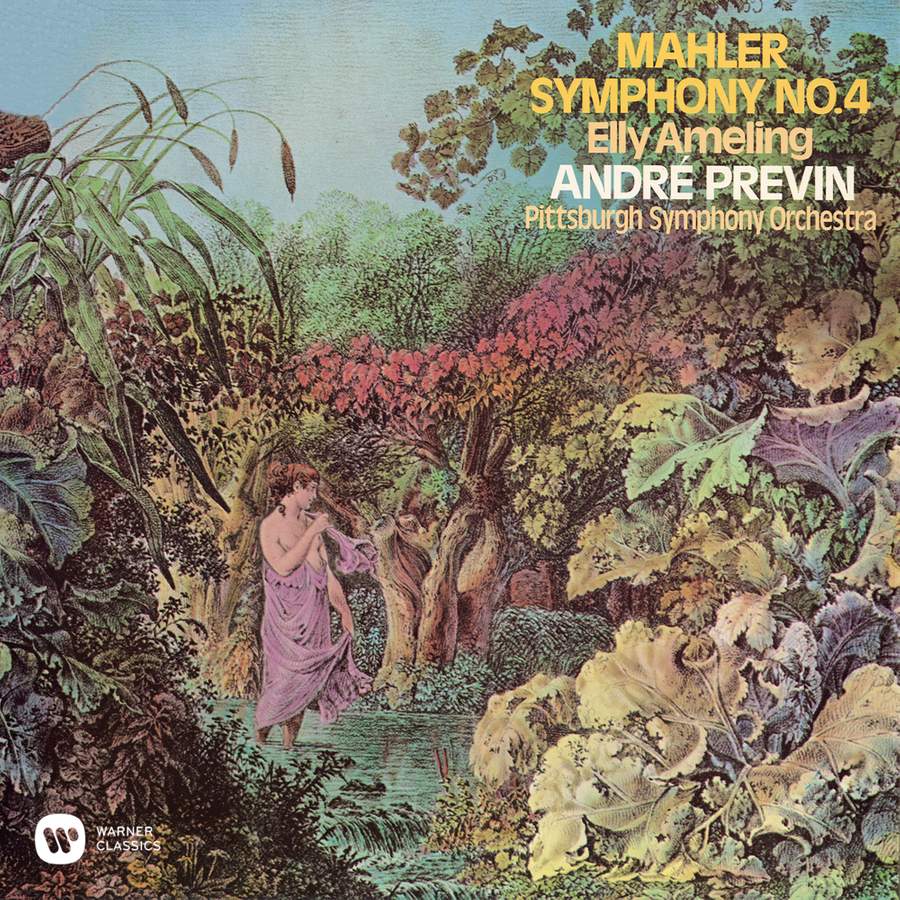

Several discs document Previn’s spell as Music Director of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra between 1976 and 1984. A lyrical, propulsive Sibelius 2 is beautifully played and recorded, and I’ve long been a fan of Previn’s big-hearted version of Mahler 4, featuring Elly Ameling as soprano soloist. And why don’t we ever hear Goldmark’s “Rustic Wedding” Symphony in concert? Bernstein’s rousing New York recording now sounds a bit dim and congested; Previn’s is definitely the one to have. Perlman’s version of Korngold’s Violin Concerto is great, as his is Sibelius. Shostakovich’s 4th and 5th Symphonies are played by the Chicago Symphony, both in readings of sombre power. There’s a ripe account of Strauss’s Eine Alpensinfonie with the Philadelphia Orchestra, and three shorter tone poems taped with the Vienna Philharmonic. Jean-Philippe Collard’s effervescent cycle of Saint-Saëns Piano Concertos was recorded during Previn’s spell with the Royal Philharmonic, and there’s an appealing disc featuring Walton’s Viola and Violin Concertos with the young Nigel Kennedy as soloist.

Several discs document Previn’s spell as Music Director of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra between 1976 and 1984. A lyrical, propulsive Sibelius 2 is beautifully played and recorded, and I’ve long been a fan of Previn’s big-hearted version of Mahler 4, featuring Elly Ameling as soprano soloist. And why don’t we ever hear Goldmark’s “Rustic Wedding” Symphony in concert? Bernstein’s rousing New York recording now sounds a bit dim and congested; Previn’s is definitely the one to have. Perlman’s version of Korngold’s Violin Concerto is great, as his is Sibelius. Shostakovich’s 4th and 5th Symphonies are played by the Chicago Symphony, both in readings of sombre power. There’s a ripe account of Strauss’s Eine Alpensinfonie with the Philadelphia Orchestra, and three shorter tone poems taped with the Vienna Philharmonic. Jean-Philippe Collard’s effervescent cycle of Saint-Saëns Piano Concertos was recorded during Previn’s spell with the Royal Philharmonic, and there’s an appealing disc featuring Walton’s Viola and Violin Concertos with the young Nigel Kennedy as soloist.

Previn’s repertoire was wider than he’s given credit for; we hear him as soloist in a pair of buoyant Mozart piano concertos, the LSO conducted by Sir Adrian Boult, and I was surprised at how good a pair of Beethoven symphonies sound. There’s some lively Haydn and Berlioz, plus two discs of Victorian songs and ballads made with Robert Tear and Benjamin Luxon. Ravi Shankar’s Sitar Concerto isn’t something I’ll return to often, but I’m glad to have heard it. We get a taste of Previn as sensitive chamber musician, as pianist in works by Brahms, Ravel and Shostakovich. Plus Sir Edward Heath conducting Elgar’s Cockaigne. What's not to like? Remasterings are good. As big box sets go, this one is a doozy, a genuine bargain considering its size (96 CDs!) and scope. Buy before it disappears, along with Previn’s RCA Walton and Vaughan Williams symphonies, and the Prokofiev and Rachmaninov piano concertos sets, both taped with Ashkenazy and available from Decca. Satisfaction guaranteed.

Previn’s repertoire was wider than he’s given credit for; we hear him as soloist in a pair of buoyant Mozart piano concertos, the LSO conducted by Sir Adrian Boult, and I was surprised at how good a pair of Beethoven symphonies sound. There’s some lively Haydn and Berlioz, plus two discs of Victorian songs and ballads made with Robert Tear and Benjamin Luxon. Ravi Shankar’s Sitar Concerto isn’t something I’ll return to often, but I’m glad to have heard it. We get a taste of Previn as sensitive chamber musician, as pianist in works by Brahms, Ravel and Shostakovich. Plus Sir Edward Heath conducting Elgar’s Cockaigne. What's not to like? Remasterings are good. As big box sets go, this one is a doozy, a genuine bargain considering its size (96 CDs!) and scope. Buy before it disappears, along with Previn’s RCA Walton and Vaughan Williams symphonies, and the Prokofiev and Rachmaninov piano concertos sets, both taped with Ashkenazy and available from Decca. Satisfaction guaranteed.

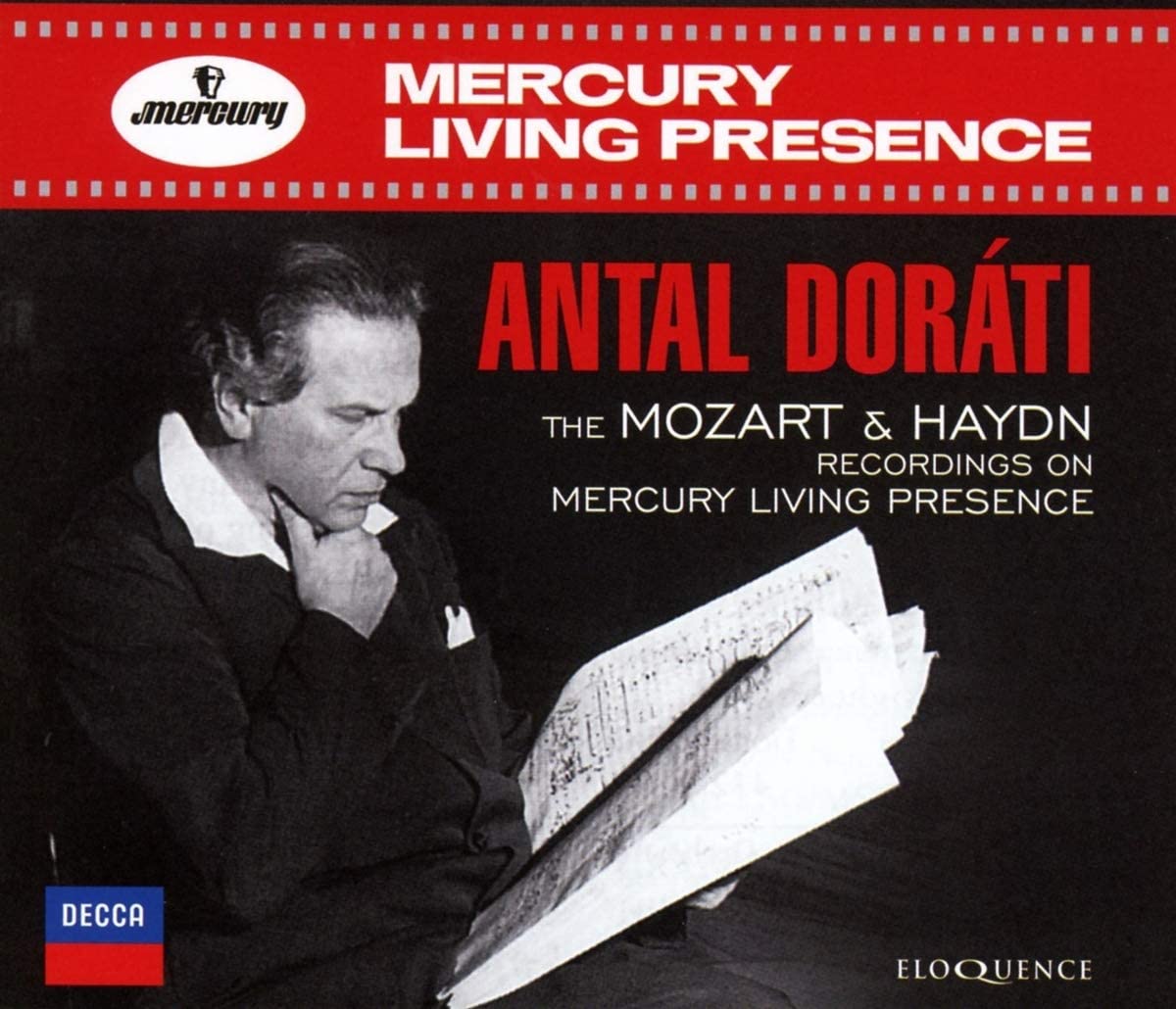

Antal Doráti: The Mozart & Haydn Recordings on Mercury Living Presence (Decca Eloquence)

Antal Doráti: The Mozart & Haydn Recordings on Mercury Living Presence (Decca Eloquence)

Connoisseurs of vintage vinyl salivate at the mention of Mercury Living Presence, an independent US label which produced scores of audiophile recordings in the 1950s and 60s. Stereo releases were mostly taped with just a single pair of well-placed microphones and the best of them still sound incredibly vivid and lifelike – track down Antal Doráti’s complete recording of Stravinsky’s Firebird with the LSO and be amazed. This four-disc set collects recordings of Haydn and Mozart taped between 1953 and 1965, predating Dorati’s groundbreaking complete Haydn cycle, released in the early 1970s. The earliest performances, recorded in mono, still sound vivid, Dorati securing sharp, alert playing from his Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra in Mozart’s Symphony No. 40. A stereo remake with the LSO is even better, and there’s an exuberant, crisply articulated LSO version of Eine kleine Nachtmusik.

Four Haydn symphonies are split between the Bath Festival Orchestra, the Philharmonia Hungarica and the LSO. These are incredibly engaging performances, full of detail. Haydn’s treacherous horn writing is well served (possibly by Barry Tuckwell?) in No. 59’s finale, and No. 45’s stormy opening is powerful. It’s fun to hear a big band version of No. 94, the "surprise" chord in the slow movement having the seismic impact of a Mahler 6 hammer blow. A lovely set, the remasterings as clear as you’d expect from this label, with each disc exceeding the 80-minute mark.

George Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra: The Forgotten Recordings (Somm Recordings)

George Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra: The Forgotten Recordings (Somm Recordings)

Most of George Szell’s recordings with Cleveland Orchestra have been reissued by Sony and Warner Classics, Sony’s vast 2018 box now commanding silly prices on Ebay. If you can’t afford that, buy this set as a stopgap, the two CDs containing recordings made for the Book-of-the-Month Club in the mid 1950s. Back then, the Cleveland musicians were poorly paid compared to their peers in starrier US ensembles, the Cleveland’s president describing it as “a first-rate orchestra with a second-rate payroll”. Players ran milk bars and operated industrial machinery to make ends meet, so Szell was happy to accept the BOMC’s offer to help his players survive. Lani Spahr’s excellent transfers were made from rare surviving copies of the original LPs and don’t betray their age, the stereo recordings made in Cleveland’s Masonic Hall full of depth and warmth. Bach’s Orchestral Suite No. 3 and Mozart’s Symphony No. 39 are dispatched with a style and grace that belies the size of the ensemble involved, and there’s a swift and witty account of Strauss’s Till Eulenspiegel showcasing the orchestra’s horns and winds.

Performances from 1955 of Brahms’s Academic Festival Overture and Haydn Variations are glorious, the orchestra’s depth of sound never oppressive; there’s such grace to the playing. Schumann 4 also sounds splendid, though the real treat is Stravinsky’s 1919 Firebird Suite, alluring and full of mischievous detail. This “Infernal Dance” has thrilling drive, and Szell’s legendary principal horn Myron Bloom provides a regal introduction to the finale. As mentioned, the remastered sound is incredibly clear. These are great performances, not just great historical performances.

Mahler: Symphony No. 10, completed and arranged for ensemble by Michelle Castelletti Ensemble Mini/Joolz Gale (Ars Production)

Mahler: Symphony No. 10, completed and arranged for ensemble by Michelle Castelletti Ensemble Mini/Joolz Gale (Ars Production)

John Storgårds and the Lapland Chamber Orchestra released a version of Michelle Castelli’s downsized Mahler 10 in 2019. This new disc distils things further in deploying just 15 players. Castelletti’s aim was to suggest “the fuller orchestral palette achieved by Rudolph Barshai, rather than the thinner textures realised in the Deryck Cooke version.” Hmm. Cooke’s Mahler 10 sounds pretty authentic to me, the most successful realisation of the work by far. Which isn’t to disparage Castelletti’s transcription. Much of the score performed by full orchestra already sounds chamber-like, and the first movement’s bittersweet first subject played on solo strings is highly effective, very like the original sextet scoring of Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht. Piano and accordion add richness to the big moments, the latter’s wheeziness more effective than harmonium. Ensemble Mini’s playing is impressively confident, the five solo strings producing a surprisingly fulsome sound when needed. Horn player Juliane Grepling deserves a shout out.

Conductor Joolz Gale’s clear-sighted, unmannered interpretation is another plus, the tempi always serving the music so that the touches of expression are all the more telling. The first movement’s ethereal coda is daringly sustained, and the first scherzo’s lopsided waltz rhythms are idiomatic. You’re reminded of how modern much of the score can sound, several passages in the three central movements suggesting Hindemith and Weill. The finale coheres beautifully. Diego Aceña Moreno’s flute solo is heartstopping and the reprise of the dissonant chord packs a punch. The closing minutes are heavenly, despite an intrusive tam-tam stroke which almost derails the final cadence. If you already love this work, you need to hear this disc. It’s beautifully recorded, the close balance serving the music well.

Moments of Vision: Music by Robin Holloway and Peter Seabourne Avant Piano Trio (Sheva Contemporary)

Moments of Vision: Music by Robin Holloway and Peter Seabourne Avant Piano Trio (Sheva Contemporary)

Robin Holloway’s Moments of Vision was a commission for the 1984 Aldeburgh Festival, this “song cycle for speaker and four players” conceived for Peter Pears. Matching spoken word with music is difficult to do well, but Holloway’s songless song cycle pulls it off. An obvious gain is that the texts, by Virginia Woolf, Walter Pater, Rilke and Siegfried Sassoon, are always audible, and Holloway’s musical response to them is correspondingly vivid. There’s a particularly bleak excerpt from Woolf’s diaries, Holloway alert to every detail. Having composer (and former Holloway pupil) Benjamin Harris as speaker is a plus – he speaks as a musician, not an orotund actor. He’s especially good in the reflective final section. Holloway’s economy is striking, and this spare, elegant work becomes more expressive with repeated listening.

Holloway’s 2017 Piano Trio is more immediately accessible, the composer managing to make the individual voices speak clearly by “treating the three instruments as separately as possible, with solos and duets rather than all-out all-of-the-way”. It’s another grower; one passage near the close, described by Holloway as being “in a celestial Palm Court idiom, only just the right side of soupiness”, is superb, and the work’s quiet close makes you want to hear it all over again.

Peter Seabourne’s Piano Trio is superficially more conventional, a four-movement work treating the three instruments as an ensemble. Allusions to classical and romantic convention come thick and fast, the occasionally florid piano writing especially impressive. And, like his teacher and mentor Holloway, Seabourne isn’t afraid to show his gift for melody, the work’s third movement opening with a sublime violin line which never quite fits its piano accompaniment; it’s like listening to a pair of 19th century violin sonatas concurrently. There’s an exhilarating finale. Performances here are excellent, the Avant Piano Trio’s pianist Alessandro Viale especially impressive in all three works.

Add comment