Best of 2021: Visual Arts | reviews, news & interviews

Best of 2021: Visual Arts

Best of 2021: Visual Arts

Our highlights of the year just gone

Despite its much delayed start, 2021 was a great year for the visual arts, and institutions and artists alike showed their resilience in agile and sensitive responses to unprecedented conditions. The plastic arts took on a new significance as people adjusted to life without human touch; equally, the experience of viewing art online revealed the extent to which tactile qualities are experienced through looking. Here are some of our thoughts on the best of the year just gone.

*

Seeing paint on canvas, walking around a sculpture and looking at the textures of plaster, stone, metal and wood was as welcome and invigorating this spring as the budding trees and lengthening days.

For this reason, as much as any intrinsic merit, Rachel Whiteread’s "apocalyptic sheds" as our critic Markie Robson-Scott called them, opened with a sense of occasion. Central London was still only a shadow of its usual self at this point, and in its intimations of disaster, Whiteread’s installations had particular resonance with the world outside.

As a mark of the artist’s greatness, Tate Britain’s retrospective of Paula Rego seemed both timely and removed from current events (Main picture: The Bride, 1994). In her review of the show, Dora Neill explored the alchemy of her art, reflecting that Rego, “is a rebel, a nonconformist, a freethinker. Rego doesn’t simply reflect the world around her, but soaks it in like an emotional sponge, before squeezing every last feeling out onto the canvas with passion and vigour.” Looking back at it, it feels like a real turning point: as a comprehensive survey of Rego’s career, it highlighted the habitual neglect of women by the major institutions. Her work is both shockingly familiar and shockingly alien: it takes an exhibition on this scale to make clear how rarely the female perspective is ever seen.

As a mark of the artist’s greatness, Tate Britain’s retrospective of Paula Rego seemed both timely and removed from current events (Main picture: The Bride, 1994). In her review of the show, Dora Neill explored the alchemy of her art, reflecting that Rego, “is a rebel, a nonconformist, a freethinker. Rego doesn’t simply reflect the world around her, but soaks it in like an emotional sponge, before squeezing every last feeling out onto the canvas with passion and vigour.” Looking back at it, it feels like a real turning point: as a comprehensive survey of Rego’s career, it highlighted the habitual neglect of women by the major institutions. Her work is both shockingly familiar and shockingly alien: it takes an exhibition on this scale to make clear how rarely the female perspective is ever seen.

As it turned out, 2021 included several exhibitions dedicated to women artists, including Eileen Agar and Sophie Taeuber-Arp, both significant figures who have faded from view over the years. Both of these shows, reviewed by Sarah Kent, were notable for their beauty and the sheer variety of the objects on display.

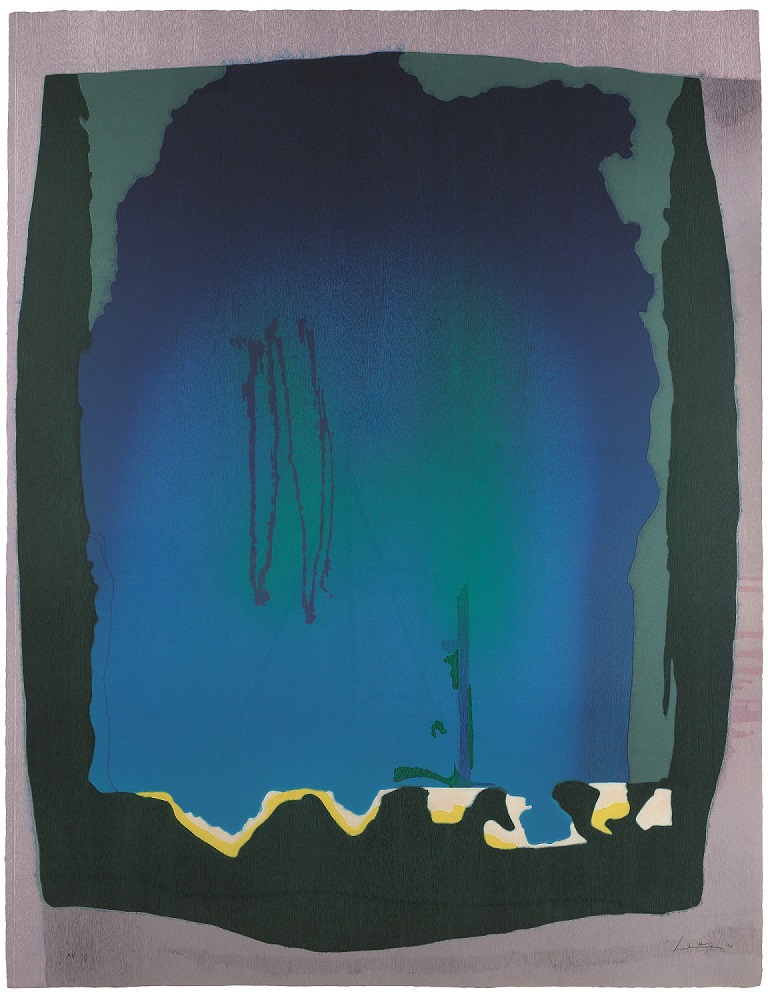

Dulwich Picture Gallery's ongoing exhibition of woodcuts by Helen Frankenthaler is similarly revelatory. Known as an innovative painter, this tendency towards invention and exploration took on a new character in her printmaking. Frankenthaler's clear vision is distilled in her woodcuts, which retain the spontaneous, painterly aesthetic of her works on canvas, belying their laborious genesis (Pictured right: Helen Frankenthaler, Freefall, 1993).

The reopening of the Courtauld Gallery felt like a long-awaited reunion with an old friend. And as with all true friendships, despite all the changes, you pick up where you left off and find it's as good as ever. Refurbishments can be alarming, but all those involved in the Courtauld renovations deserve heartfelt congratulations and thanks – it really is the old place, just better. Florence Hallett

*

Sarah Kent

Have this year’s exhibitions been unusually good? Or did lockdown leave me feeling so starved of the real thing, that being able to go into a gallery once more and experience artworks in the flesh, as it were, was a huge delight? Probably both. One of the first joys was a retrospective of Eileen Agar, the only woman to be included in The International Surrealist Exhibition of 1936, which introduced artists like Salvador Dali and Max Ernst to Londoners. Today she is best known for sculptures like the Angel of Anarchy, 1936, a plaster head draped in beads and feathers, and assemblages of marine bric-a-brac which double as absurdist hats (pictured above: Agar wearing Ceremonial Hat for Eating Bouillabaisse, 1936). But the Whitechapel Gallery exhibition revealed her to be a fine photographer, painter and collagist as well.

One of the first joys was a retrospective of Eileen Agar, the only woman to be included in The International Surrealist Exhibition of 1936, which introduced artists like Salvador Dali and Max Ernst to Londoners. Today she is best known for sculptures like the Angel of Anarchy, 1936, a plaster head draped in beads and feathers, and assemblages of marine bric-a-brac which double as absurdist hats (pictured above: Agar wearing Ceremonial Hat for Eating Bouillabaisse, 1936). But the Whitechapel Gallery exhibition revealed her to be a fine photographer, painter and collagist as well.

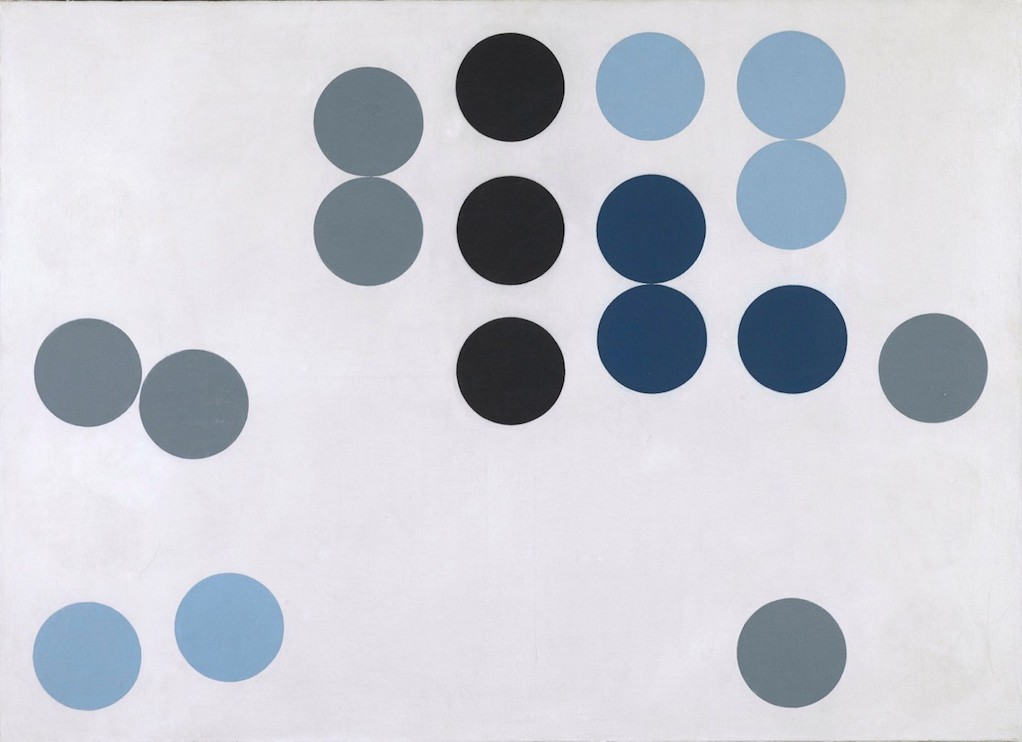

Tate Modern’s retrospective of Sophie Taeuber-Arp was a revelation. She was tragically killed by carbon monoxide poisoning aged only 53 and at the height of her powers; but boy did she pack a lot into her short life! She is best known for her textile designs, but that is to overlook her Dadaist performances at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich during World War I, and her sculptures, puppets, murals, stained glass, furniture and architectural designs. The highlights of the show, though, were her abstract drawings and paintings (pictured below: Animated Circles, 1934) that sizzle with tension and dance with implied motion. It was an especially good year for painting exhibitions. At the Royal Academy where he studied, Michael Armitage showed us how to juxtapose passages of fluent realism with areas of sketchy abstraction and filmy ambiguity. Melding the various elements into a legible whole takes remarkable skill; goodness, can this man paint! Such complexity stems partly from the fact that, having been born in Kenya, in 1984, and educated in England, he brings to bear both Western and East African viewpoints. You might think you’ve understood his pictures, but the next minute things can dissolve into uncertainty.

It was an especially good year for painting exhibitions. At the Royal Academy where he studied, Michael Armitage showed us how to juxtapose passages of fluent realism with areas of sketchy abstraction and filmy ambiguity. Melding the various elements into a legible whole takes remarkable skill; goodness, can this man paint! Such complexity stems partly from the fact that, having been born in Kenya, in 1984, and educated in England, he brings to bear both Western and East African viewpoints. You might think you’ve understood his pictures, but the next minute things can dissolve into uncertainty.

I’m not a fan of big mixed shows – too many competing voices and too few examples of anyone’s work to relate to fully. But the Hayward Gallery’s Mixing It Up was a tour de force because the work was so good and so varied. Ranging in age from 87 to 28, the 32 artists were from this country, yet a third were born elsewhere – including Belgium, China, Columbia, Germany, Iraq, Zambia and Zimbabwe. And the work varied in scale from pocketbook-sized canvases to wall-sized friezes and from detailed observations of the external world to gestural outpourings of pure energy. The result was a celebration of painting’s potential to express anything from private emotions and intimate concerns to global issues and collective trauma.

Nor am I a particular fan of Isamu Noguchi’s work yet the Barbican retrospective (pictured right) was so beautifully installed that I was captivated. His elegant abstract sculptures were lit by his magical paper lanterns. The half-American, half-Japanese artist wasn’t interested in distinctions between art and design. Wanting to “bring sculpture into a more direct involvement with the common experience of living”, he designed a bakelite radio in the shape of a head, a chess set, a coffee table whose glass top rests on sleek black curves, and playgrounds with slides, helter skelters and climbing frames that are essentially outdoor sculptures. Noguchi died in 1988, having lived through turbulent times. The Barbican’s survey provided fascinating insights into the mind of a restless spirit.

Nor am I a particular fan of Isamu Noguchi’s work yet the Barbican retrospective (pictured right) was so beautifully installed that I was captivated. His elegant abstract sculptures were lit by his magical paper lanterns. The half-American, half-Japanese artist wasn’t interested in distinctions between art and design. Wanting to “bring sculpture into a more direct involvement with the common experience of living”, he designed a bakelite radio in the shape of a head, a chess set, a coffee table whose glass top rests on sleek black curves, and playgrounds with slides, helter skelters and climbing frames that are essentially outdoor sculptures. Noguchi died in 1988, having lived through turbulent times. The Barbican’s survey provided fascinating insights into the mind of a restless spirit.

Its more than 50 years since Yoko Ono first presented Mend Piece at the Indica Gallery, London in the show through which she met John Lennon. And in the intervening years its meaning has subtly changed. Ono’s invitation to “mend carefully” hangs on the wall of Whitechapel Gallery (until January 2) above four tables strewn with dozens of broken cups and saucers and everything you need to attempt a botched repair – glue, sellotape, scissors and string.

“Think of mending the world at the same time,” Ono suggests. At the height of the Vietnam War, world peace was on her mind. Now, though, with climate change the most pressing issue, “Mending the world” seems more like an exhortation to save the planet. A big ask and no-one came near creating anything resembling a cup and saucer; instead, most contented themselves with incoherent jumbles. A sign of the times? Prelude, a six-screen film projection (pictured above) by Kehinde Wiley, is at the National Gallery. The American artist took a group of black Londoners to Norway and filmed them in the snow-bound emptiness of mountains, lakes and forests. They look dramatically out of place in the inhospitable whiteness – a compelling metaphor for living as a black person in a world controlled mainly by whites.

Prelude, a six-screen film projection (pictured above) by Kehinde Wiley, is at the National Gallery. The American artist took a group of black Londoners to Norway and filmed them in the snow-bound emptiness of mountains, lakes and forests. They look dramatically out of place in the inhospitable whiteness – a compelling metaphor for living as a black person in a world controlled mainly by whites.

Five individuals smile to camera; snowflakes snagging in their hair, eyebrows and lashes, they hold our gaze as the camera glides in for a close-up, then pulls back only to return and reveal muscles twitching under the strain. Is this what true resilience looks like – maintaining a smile under adverse circumstances? Given how constrained life has been during the long months of the pandemic, this notion feels strikingly apposite. The exhibition is on until 18 April 2022, so there’s plenty of time to catch it.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Bogancloch review - every frame a work of art

Living off grid might be the meaning of happiness

Bogancloch review - every frame a work of art

Living off grid might be the meaning of happiness

Do Ho Suh: Walk the House, Tate Modern review - memories are made of this

Home sweet home preserved as exquisite replicas

Do Ho Suh: Walk the House, Tate Modern review - memories are made of this

Home sweet home preserved as exquisite replicas

Ed Atkins, Tate Britain review - hiding behind computer generated doppelgängers

Emotions too raw to explore

Ed Atkins, Tate Britain review - hiding behind computer generated doppelgängers

Emotions too raw to explore

Echoes: Stone Circles, Community and Heritage, Stonehenge Visitor Centre review - young photographers explore ancient resonances

The ancient monument opens its first exhibition of new photography

Echoes: Stone Circles, Community and Heritage, Stonehenge Visitor Centre review - young photographers explore ancient resonances

The ancient monument opens its first exhibition of new photography

Hylozoic/Desires: Salt Cosmologies, Somerset House and The Hedge of Halomancy, Tate Britain review - the power of white powder

A strong message diluted by space and time

Hylozoic/Desires: Salt Cosmologies, Somerset House and The Hedge of Halomancy, Tate Britain review - the power of white powder

A strong message diluted by space and time

Mickalene Thomas, All About Love, Hayward Gallery review - all that glitters

The shock of the glue: rhinestones to the ready

Mickalene Thomas, All About Love, Hayward Gallery review - all that glitters

The shock of the glue: rhinestones to the ready

Interview: Polar photographer Sebastian Copeland talks about the dramatic changes in the Arctic

An ominous shift has come with dark patches appearing on the Greenland ice sheet

Interview: Polar photographer Sebastian Copeland talks about the dramatic changes in the Arctic

An ominous shift has come with dark patches appearing on the Greenland ice sheet

Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker, Whitechapel Gallery review - absence made powerfully present

Illness as a drive to creativity

Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker, Whitechapel Gallery review - absence made powerfully present

Illness as a drive to creativity

Noah Davis, Barbican review - the ordinary made strangely compelling

A voice from the margins

Noah Davis, Barbican review - the ordinary made strangely compelling

A voice from the margins

Best of 2024: Visual Arts

A great year for women artists

Best of 2024: Visual Arts

A great year for women artists

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Flashing lights, beeps and buzzes are diverting, but quickly pall

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Flashing lights, beeps and buzzes are diverting, but quickly pall

Add comment