Mahler: Symphony No. 4 Czech Philharmonic Orchestra/Semyon Bychkov,with Chen Reiss (soprano) (Pentatone)

Mahler: Symphony No. 4 Czech Philharmonic Orchestra/Semyon Bychkov,with Chen Reiss (soprano) (Pentatone)

Semyon Bychkov’s Mahler 4 is the first volume of a projected cycle from an orchestra with a surprisingly small Mahler discography. Mahler was born in what is now the Czech Republic, and the fanfares and funeral marches which fill his symphonies echo those he heard while growing up in Jihlava. The Czech Philharmonic does have recorded form in Mahler: Vaclav Neumann’s late 1970s symphony cycle on Supraphon is as idiomatic as they come, and there’s a thrilling vintage version of No. 9 conducted by Karel Ancerl. Neumann’s 4th stands up very well, with some wonderfully cheeky wind playing and an earth-shaking eruption near the end of the slow movement. Bychkov’s performance starts off sleeker and less distinctive, though this orchestra’s transparent, warm sound is still very recognisable. Mahler’s contrapuntal lines are always audible, Bychkov highlighting unexpected details without interrupting the first movement’s flow. The unison flute theme six minutes in is glorious, and you can really hear the swirling string writing underneath.

Bychkov is good at rapture; the radiant strings and horn passage before the first movement’s clattering close is exquisite. And sample the scherzo’s second trio, 50 seconds of sun-drenched loveliness. This third movement is one of the slower ones on disc but doesn’t drag, and the big climax is suitably imposing. Soprano Chen Reiss is a pure-toned delight in the finale. An enjoyable disc, captured in glowing sound.

MM 1786: Mozart Momentum Leif Ove Andsnes, Mahler Chamber Orchestra (Sony Classical)

MM 1786: Mozart Momentum Leif Ove Andsnes, Mahler Chamber Orchestra (Sony Classical)

These Mozart performances, all involving Leif Ove Andsnes – one solo piano piece, one piano trio, one piano quartet, one concert aria with piano, and two piano concertos – are of works written in the same year, 1786, the year of Figaro. Andsnes describes 1786 as Mozart’s “most productive year” and is in awe of the composer’s quicksilver ability to “go from a carefree atmosphere to total loneliness in a split second.” This set is the second of two releases looking into successive years in Mozart’s life. How to characterise these performances? It’s almost easier to describe what they aren’t: they are never histrionic, overwrought or hurried. The single solo piano work, the D major Rondo K.485, is a piece which can elicit a whole range of approaches from pianists. The marking is a simple “Allegro”. There are those, like Víkingur Ólafsson or Mitsuko Uchida, who play it fast and virtuosically, and make it glint and gleam. Others, like Maria João Pires – certainly back in her Denon days – used to play it slower, in a manner that emphasised the candidness and simplicity, perhaps with a hint that “anyone can play this”. And Andsnes? He finds his own way well within these two extremes. The playing is well-judged, sensible.

Another case of navigating between extremes, this time emotional, comes in the Concert Aria “Ch’io Mi Scordi Di Te”, an insertion aria for Idamante in Idomeneo. Soprano Christine Karg has made another, remarkably different recording of this work with Jonathan Cohen’s Arcangelo. The Arcangelo recording is at lower pitch. Karg produces a much rawer vocal timbre, with a more fluid approach to tempo. She brings out the manic and the angry, rather than the reassuring aspects of the song text. By contrast, her performance here, under Andsnes's influence is far more beautiful, dignified and in control.

This solo piano piece and the chamber works were recorded beautifully and naturally in that wonderful space the Sendesaal in Bremen, with the section principals from the Mahler Chamber Orchestra, and they are the works here that I have been most drawn to. Again, it is all about a sound and sensible feel for tempi that allow the emotional shifts to come naturally. In the two great piano concertos, K.488 in A major and K.491 in C minor, I have been particularly drawn in to the joyous world Andsnes inhabits in the B flat major larghetto at the heart of the C minor concerto. It is quite simply a wonderful place to spend some time. The dialogue between piano/strings and the Mahler Orchestra's strong and characterful wind players is gorgeous. And those blissful surroundings are particularly welcome after a very dark reading indeed of the C minor opening movement. The two piano concertos were recorded in the Musikverein in Vienna. It is remarkable how John Fraser and his engineers have made that acoustic sound just as natural as the Bremen acoustic is for the small groups. – Sebastian Scotney

Saint-Saëns: Complete Symphonies Orchestre National de France/Cristian Măcelaru (Warner Classics)

Saint-Saëns: Complete Symphonies Orchestre National de France/Cristian Măcelaru (Warner Classics)

Saint-Saëns wrote five symphonies, though only three have numbers. Of those three, only one ever gets performed. And while No. 3 is deservedly famous, the others contain much attractive music. Take the Symphony in A, its first movement cheekily based around a famous four-note theme from Mozart 41. Composed in 1850 when Saint-Saëns was just 15, it’s incredibly assured, like early Beethoven with fancier, very French wind writing. Cristian Măcelaru’s Orchestre National de France are superb in the ebullient finale, the chattering winds so typical of this composer. No. 1 followed three years later, a delectable blend of the heroic and the homely. Vintage French recordings offer more authentic, unhomogenised sonorities in the last movement’s brassy march (try Jean Martinon’s set, also on Warner), but this performance is a lot of fun. You can hear hints of the mature Saint-Saëns in the fugal apotheosis, never overblown in this performance. And the little “Marche-Scherzo” second movement is possibly the most charming five minutes of music you’ll hear all year.

The unnumbered “Urbs Romana” symphony was completed in 1857 and published posthumously. Any musical allusions to Ancient Rome aren’t obvious, though the eloquent funeral march could indeed be seen as “an affecting lament to the passing of a great empire” and the work’s scale is imposing. Saint-Saëns’ ‘official’ Symphony No. 2 is better value, a lightly-scored delight which ranks alongside Bizet’s Symphony in C in terms of entertainment value. Again, it’s deliciously played. Recordings of the "Organ Symphony” where the soloist is overdubbed after the event don’t do it for me. Happily, Măcelaru’s performance has organist Olivier Latry actually joining the orchestra in Paris’s Auditorium de Radio France, and it shows, the instrument perfectly balanced. Listen to how he steals in at the start of the “Poco Adagio”, as if someone’s just switched the central heating on. The finale’s big reveal doesn’t disappoint, though I was equally impressed by the scherzo’s quirky trio section, the unnamed piano duettists enjoying their moment in the sun. The final minutes are uplifting without any hint of pomposity; follow with a score and witness the music slowing down as it appears to accelerate. Other outstanding new recordings of these works are available; I’m fond of Thierry Fischer’s Utah Symphony cycle on Hyperion, replete with interesting couplings. But Măcelaru’s set scores in terms of economy, the three discs squeezed into a reasonably-priced gatefold package with attractive artwork. A winner.

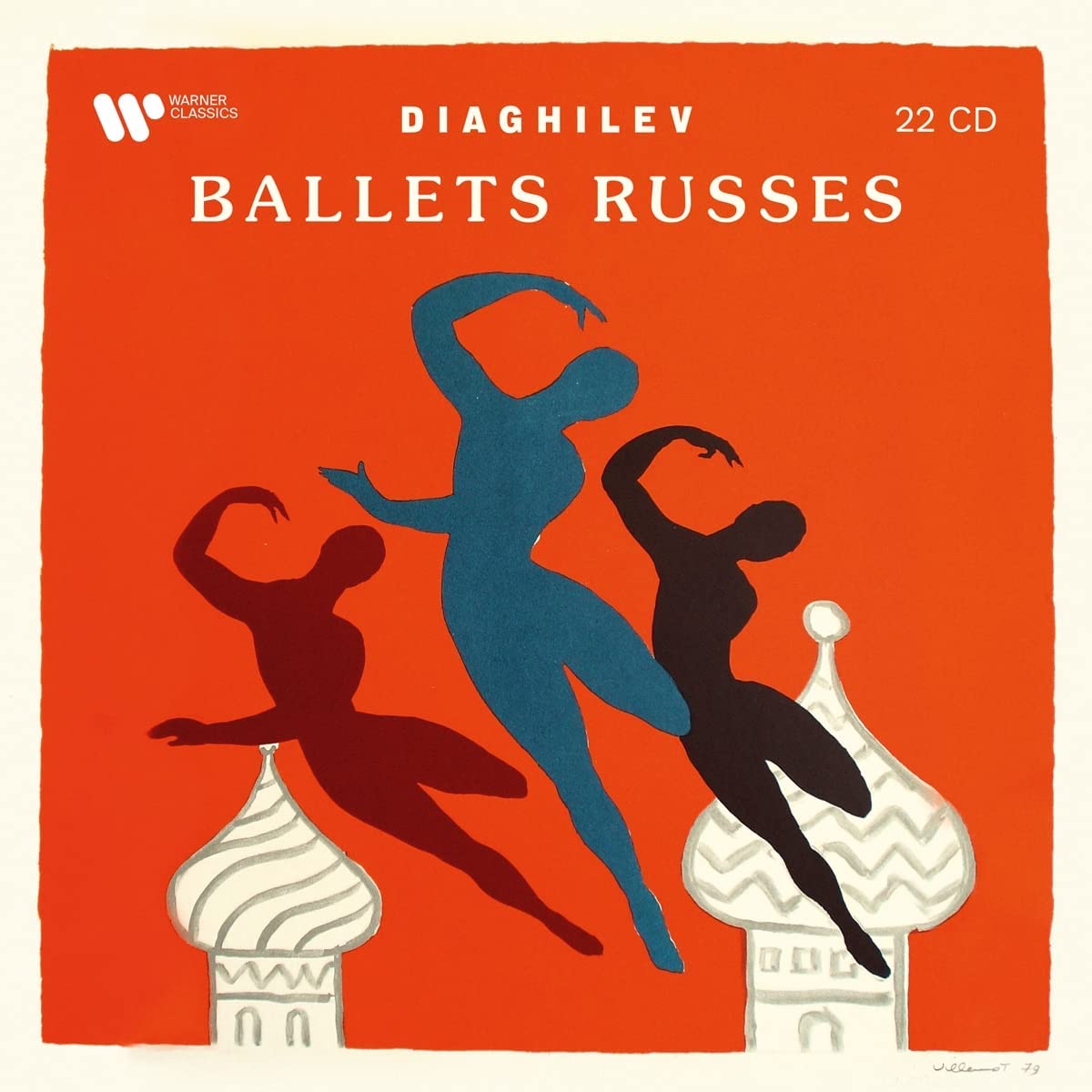

Diaghilev – Ballets Russes (Warner Classics)

Diaghilev – Ballets Russes (Warner Classics)

This is a golden age for the CD box set, and keeping up with the huge swathes of stuff being recycled and reissued by the major labels is exhausting. Shop wisely and there are incredible bargains to be had. Like this one, tracing through music the 20-year existence of the ballet company founded by impresario Sergei Diaghilev in 1909. Many of these scores are now popular classics, and it's to Warner Classics’ credit that so many of the performances chosen for inclusion are zingers. Igor Markevich’s vicious, incisive 1959 Rite of Spring still sounds vivid, and the vintage Philharmonia’s playing is remarkable. Ravel’s Daphnis and Debussy’s Jeux are conducted by André Cluytens, his Paris Conservatoire forces producing an echt-French sonority. Martha Argerich and Nelson Friere are among the pianists in Charles Dutoit’s account of Stravinsky's Les Noces, and Tchaikovsky’s Sleeping Beauty and Swan Lake are both conducted by André Previn. You’d happily buy the box for those discs alone, but the rarities make it a mandatory purchase. The discs are arranged chronologically from 1909 to 1929, when Diaghilev’s death and the company’s huge debts forced its closure.

Why not start with the suite from Florent Schmitt’s La tragédie de Salomé from the 1913 season, brilliantly handled by Jean Martinon, or Gennady Rozdhestvensky’s Hague Residentie Orchestra in Nikolai Tcherepnin’s exquisite Narcisse et Écho. There’s a condensed version of Strauss’s ballet Josephslegende under Rudolph Kempe, a gorgeous obscurity. Strauss wasn’t convinced by the work, complaining that writing music about the saintly biblical hero was “a hell of an effort.”

Schumann’s Carnaval was choreographed in 1910, its collective orchestrators including Glazunov, Rimsky-Korsakov and Liadov; Robert Irving’s vivid 1959 recording appears on CD for the first time. It’s fun, though even better is Alceo Galliera’s contemporaneous account of the Respighi/Rossini ballet La Boutique Fantasque, Respighi orchestrating eight of the older composer’s Péchés de vieillesse. It’s pure joy, as inventive as Stravinsky’s Pulcinella (conducted here by Neville Marriner). Tomassino’s The Good Humoured Ladies (performed in 1917) does something similar with a sequence of Scarlatti keyboard sonatas. More baroque jiggery-pokery comes in the form of Beecham’s The Gods Go a’Begging, a ripely orchestrated sequence of Handel excerpts. There’s enough here to keep you exploring for months. Other well-known figures include Dukas, Falla, Milhaud, Poulenc and Prokofiev plus a disc of historical recordings which features a dimly-recorded 1931 account of Stravinsky’s Rite with the Grand Orchestre Symphonique led by Pierre Monteux. How much more authentic can you get? Sturdy, aesthetically appealing packaging and decent notes add to this set’s appeal. Buy it while you can.

When Sleep Comes Tenebrae/Nigel Short, with Christian Forshaw (saxophone) (Signum Classics)

When Sleep Comes Tenebrae/Nigel Short, with Christian Forshaw (saxophone) (Signum Classics)

Subtitled "Evening meditation for voices and saxophone", Tenebrae's When Sleep Comes inevitably invites comparisons with the albums recorded for ECM by saxophonist Jan Garbarek and the Hilliard Ensemble, the first of which was a global bestseller. This is a different beast, however; whilst Garbarek improvised freely over unadorned medieval originals, composer and soloist Forshaw subtly reworks some of the originals, in effect becoming an additional vocalist. Comparing Nigel Short's Tenebrae singing (beautifully) Tallis's "Sancte Deus" with the Tallis/Forshaw "O nata lux" is fun, Forshaw subtly accentuating Tallis's harmonic boldness. Gibbons's "Drop, drop slow tears" is equally effective, Forshaw's understated solo line providing an idiomatic introduction and epilogue.

Several numbers really stand out: soprano Victoria Meteyard's duetting with Forshaw is terrific in Short's reworking of Hildegard von Bingen's "O vos imitatores", and "straight" takes on music by Victoria and Owain Park are beautifully done. But I did find myself craving a touch more adventure and boldness in some of the arrangements. The hymn "Abide with me" is a case in point, Forshaw's version sounding almost too respectful. It's striking how contemporary the closing number, Brumel's "Lamentations" feels in comparison. Still, the performances can't be faulted, and the acoustic of All Hallows, Gospel Oak, casts a warm glow over proceedings.

Add comment