Laurent Cantet: 'Young people have different preoccupations nowadays' – interview | reviews, news & interviews

Laurent Cantet: 'Young people have different preoccupations nowadays' – interview

Laurent Cantet: 'Young people have different preoccupations nowadays' – interview

The award-winning director discusses his new film, The Workshop, in which some newbie writers get in a tizz over the fine line between fact and fiction

Like Ken Loach and the Dardennes brothers, Laurent Cantet is a filmmaker with a keen interest in social issues and themes, often using non-professional actors and a naturalistic approach, but perfectly willing to inject a littl

The Frenchman’s early, calling-card films dealt with the workplace: Human Resources (1999) tackled industrial relations in a provincial factory and the divisive effect it has on a father-son relationship; Time Out (2001) concerned an executive’s painstaking attempt to fabricate a glamourous new working life, because he doesn’t have the courage to tell his wife he’s been sacked – the ruse sending him spiralling out of control.

The Class, which won the prestigious Palme d’Or in Cannes in 2008, follows a year in the life of a single classroom in a tough, Parisian multi-cultural high school, whose charismatic teacher encourages the kids in open debate on issues of identity, race and discipline, his methods both appealing and hazardous.

The students' presence on camera is so natural and seemingly unscripted that it would be easy to assume that The Class is a fly-on-the-wall documentary. It’s not, but nor is it straightforward fiction, Cantet’s process being to cast young non-actors from the world he was depicting, not to play themselves per se but to workshop characters not far removed.

Cantet’s interest in youth continued with Foxfire (2012), based on the novel by Joyce Carol Oates, which follows a very unusual girl gang in 1950s New York. And now, with The Workshop.

The genesis of the new film was an actual writing workshop, conducted by an English novelist in La Ciotat, in the south of France, in 1999. Its aim was to provide an opportunity for a dozen or so young people to collaborate on a novel; their only condition was that it should take place within the town, which at the time was still recovering from the closure of its shipyard.

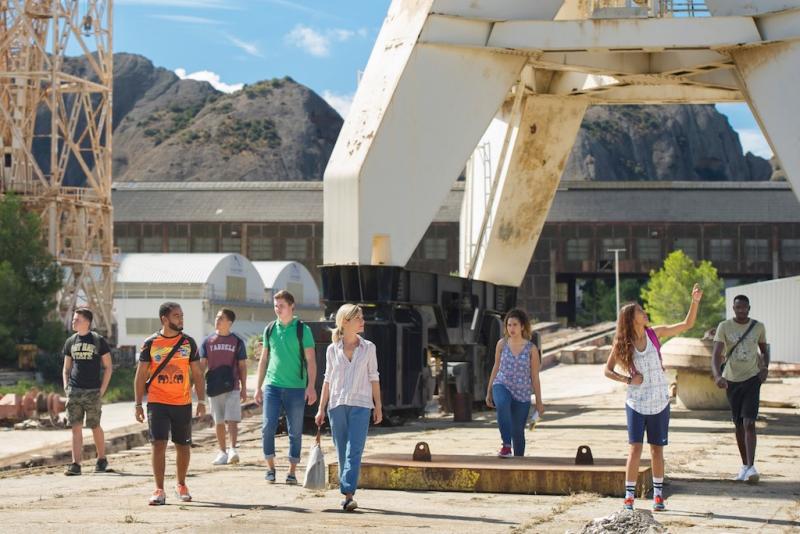

Ciotat remains the setting of the film, which Cantet has co-written with his regular writing partner Robin Campillo (who recently enjoyed a massive hit as a director, with 120 BPM). Now a French novelist, Olivia (Marina Foïs, the only professional in the main cast), leads the summer workshop, whose young participants are charged with writing a crime thriller together.

The odd one out amongst them is Antoine (Matthieu Lucci), intelligent and with plenty of ideas, but provocative, his racially incendiary language and unbridled delight in his violent scenarios constantly riling the others. As Olivia becomes increasingly fascinated and troubled by the teenager, we begin to wonder whether he’s about to manifest the sort of violence he likes to describe. As with all Cantet’s work, it’s a challenging, thought-provoking and often disquieting film.

DEMETRIOS MATHEOU: You were developing this on and off with Campillo for many years. How did the script change over the course of that period?

LAURENT CANTET: We first started thinking about this 12 years ago. What we’ve kept is the workshop, as a device. When the actual workshop was held in La Ciotat the aim was to help the youngsters to understand the working-class past of the city, especially the shipyard that had been closed down. Nowadays that history has lost its meaning. Nevertheless, I thought that the workshop was an interesting way of allowing the youngsters to say how they feel about life.

Young people have different preoccupations nowadays. The world is different, it’s more violent, their possibilities have been reduced. In small cities such as La Ciotat youngsters are very often bored. So this is what I really wanted to look at.

And you never considered moving the location?

No. It was always set in La Ciotat because I think it’s a city that has a specificity – the traces of the past are still easy to see, with the shipyard, the cranes that still exist. So, in a way, even if the working-class past is not as meaningful for the youngsters, they are still confronted with it, through all those traces.

Can you describe how you work with the young actors?

When the first version of the screenplay was completed, we conducted a sort of 'open casting', where we went to sports clubs, theatre groups, bars, and waited outside high schools. It was a way to meet a few hundred young people from the area, among whom I chose the actors.

I then led my own two-week intensive 'workshop' with them, the idea being that I would tap into their personal experiences and characters to enrich the film. Gradually, individual scenes were fleshed out. From that standpoint, it could be said that they never learned their roles; rather they assimilated their roles into their personalities. And the exchanges that came out of this pre-production work influenced the writing.

Just how much do those rehearsals and conversations feed back into the script?

A lot. The way I phrase things is going to come from their own words, it's their words that are going to be in the scenes. For instance, a sequence that in the [original] script would have two lines would then become much longer, like the scene where they talk about what they find on the internet.

There’s an obvious resonance between this film and The Class, and the fact that you have young people in debate with each other and a teacher, as a device for speaking about their issues.

There is. On the other hand, I find that the film has a stronger relation with Time Out. In a way Antoine resembles the main character of that film [pictured left, played by Aurélien Recoing]. Antoine doesn’t feel at home anywhere. In a way he’s a wanderer too, and he's always hoping that something will pop up and change his life. He's also constantly making fiction. He says at the beginning of the workshop, 'We're not here to scrutinise ourselves, we're here to try to write a bigger story and find something that is going to take us out of our shitty daily life'.

There is. On the other hand, I find that the film has a stronger relation with Time Out. In a way Antoine resembles the main character of that film [pictured left, played by Aurélien Recoing]. Antoine doesn’t feel at home anywhere. In a way he’s a wanderer too, and he's always hoping that something will pop up and change his life. He's also constantly making fiction. He says at the beginning of the workshop, 'We're not here to scrutinise ourselves, we're here to try to write a bigger story and find something that is going to take us out of our shitty daily life'.

Matthieu Lucci, who plays Antoine [pictured below, with Marina Foïs], is a great discovery. I understand he hadn't acted before. How did you find him?

He was having a cigarette with his pals when the casting director gave him a leaflet, and he came the next day to make a trial. He was very convincing, but [finding him] had been so easy that I doubted he was going to be the right actor, so continued to see other people. But I kept coming back to him, and each time I saw how deeply he understood what was going on in the film. And his nature really fitted what I wanted, which was a character who could be really worrying, almost frightening, and at the same time impossible to accept as such. I really didn't want us to judge the character, and Matthieu's palette of emotion and his palette of acting was subtle enough to prevent us from doing this.

There's also something that really moved me. When Matthieu actually started to get into the character, acting him, he said to me: ‘The more time passes the more I love Antoine. And at the same time I think he's a real arsehole’. This fitted the complexity of the relationship that I wanted us to have with the character – the kind of person you love, but regret loving.

There's also something that really moved me. When Matthieu actually started to get into the character, acting him, he said to me: ‘The more time passes the more I love Antoine. And at the same time I think he's a real arsehole’. This fitted the complexity of the relationship that I wanted us to have with the character – the kind of person you love, but regret loving.

That reflects the complexity of the film as a whole. One thing I found interesting is that you create a very authentic slice of life, but at the same time you infuse the plot with genre tropes – on one level, Antoine is a young outsider with a gun. It’s a very delicate balance.

All my films are looking for this. They speak about the world we live in – here it's about violence, fundamentalism, political extremism, the lack of future for those youngsters – but they are not sociological treatises. I'm using a sociological backdrop, but it's very subtle. It's the story that comes first, and the story is always conveyed by characters.

The interesting thing here is that the film was concerned with fiction right from the start, and the fiction comes through the characters. With Olivia’s help the youngsters are writing a noir novel, and little by little the film itself becomes a thriller, which addresses the very questions that the participants of the workshop are asking themselves – can we write about violence the way Antoine wants to do it? What difference is there between life and fiction? And all this is intertwined with the social preoccupations.

At the end we get something that can be frightening, something that can also be troubling. The most troubling thing about Antoine in my eyes is the difficulty he has in grasping the difference between literary violence, which can be given full expression in a thriller, and real violence.

What interests me as well is that it is the literary process that is going to help Antoine to get to know himself. As he manages to find the appropriate words to speak about his boredom and his feelings about violence, he's going to be able to overcome this, to leave the city and actually grasp his life and do what he wants.

In her own work, Olivia has difficulty writing about people younger and less privileged than her. Might that reflect your own challenges?

Antoine accuses Olivia of being the puppeteer who does what she wants with them. Obviously these are the kinds of questions that I'm asking myself when I'm working with young people. I think I can prevent this kind of problem through the long process of rehearsals, the long process of conversations with the people I'm working with.

- The Workshop is released in cinemas on 16 November

- Read more interviews on theartsdesk

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Add comment