Erik Poppe and Andrea Berntzen: 'When white young men do stuff like this, we just shake our heads' | reviews, news & interviews

Erik Poppe and Andrea Berntzen: 'When white young men do stuff like this, we just shake our heads'

Erik Poppe and Andrea Berntzen: 'When white young men do stuff like this, we just shake our heads'

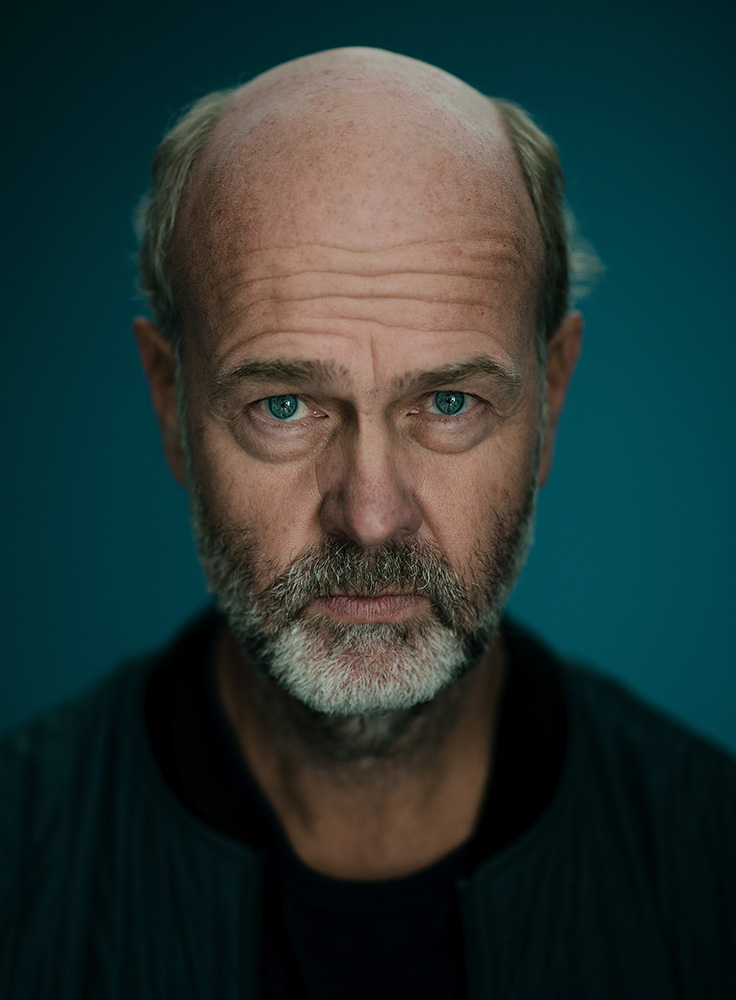

Director and lead actor of Utoya: July 22 on working with survivors to recreate the Norwegian terror attack

On 22nd July 2011, on a tiny island off the Norwegian coast, 69 young people were killed, with another 109 injured in a terrorist attack. It was the darkest day in Norway since World War Two, and one that is still evident in its news, politics and society today.

Utoya: July 22 is his response. Working directly with the survivors and families, he sought to tell their story and remind people of what really happened. Although gripping, it is not entertainment – it is a terrifying, claustrophobic and deeply unsettling film. It is not there to sell tickets; it is the least anyone can do if they wish to understand the fear and pain of those who were there.

The film is told entirely through one shot, following debuting actor Andrea Berntzen as she scrambles across the island, hiding from gunfire and searching for her sister. Poppe spares no details: children die slowly on screen from their wounds, and happy endings are in short supply. It is brazen, and perhaps one of the most affecting films ever created.

The film is released today, only two weeks after Paul Greengrass’ 22 July about the same attack. But whereas Greengrass studies the killer, Poppe was adamant that the focus must be on the victims. Owen Richards spoke with the director, and lead actor Andrea Berntzen, about making such a difficult film.

OWEN: Before we talk about the film, I wanted to ask what you both remember about the day of the attack?

ERIK: Well I was in my car on my way back to Oslo after a couple of weeks of vacation in south Norway. My assistant, who works in our Oslo office, called me in panic and said “something crazy has happened. There’s a bomb or something just close to our office.”

It was a really dramatic moment, all the windows were broken, you felt that the whole downtown was in ruins. All the focus was on what had happened, and who might this be, for the next couple of hours. When I arrived at Oslo I was supposed to be attending a birthday party that afternoon. We did go to that birthday party, but everyone was just watching the news on the TV. Then, the next breaking news was there was something going on at the island. A lot of us remember that the attack was broadcast live, it was really a defining moment.

ANDREA: I was 13 years old at the time of the attack. We were actually driving from the south of Norway as well, it was summertime and my mum lived in Oslo, so the bomb really caught my attention. Then I remember waking up the next day and seeing the shocking numbers of how many people were shot and killed on the island, shocked that everything was planned by the same guy.

At the time I remember being scared but I don’t think I understood the severity of the situation; I don’t think I was old and mature enough to understand that these were human lives being taken away, and that’s something I didn’t really understand until I started working on this project.

Erik, when did you decide this was a story you wanted to tell on film?

ERIK: Well I started with this project about three years ago. I was having a reaction to the fact our focus wasn’t on what happened anymore, it was on the perpetrator and all the stuff he made up to get attention. It was also on the technical issues, such as how to rebuild Oslo after the bomb, where to place the memorial site, and also this big commission investigating why the police didn’t act earlier.

I asked the survivors and the families how they felt, and they really shared the same feelings. We started to look into if it would be possible to make a movie, tell their story about what happened, but seen entirely from the victims’ perspective to remind us what happened.

The survivors told me they received death threats from right wing extremists when they spoke out about what happened. They wrote to them very openly on social media saying that they think it’s too bad they didn’t die that day. I wanted to help wake up the other part of our society, so they can take action against cruelty such as this.

The movie was made because I wanted to explore if we were able to portray the feeling of being trapped on that island. We know a little of what was going on, and every so often we’ll read about such atrocities, but ability to empathise with the victims appears to be limited. I wanted to know whether we could tell this story in the most truthful way possible. The survivors and the families were really supporting the idea, and wanted to stand behind this movie.

The camera is with Andrea throughout, how important was it finding the right actor for this role?

Well that was the question, whether it was possible to find those young actors, amateurs, who would be able to perform and express those feelings in a natural and truthful way. The thing is, because it was done in one take, there wouldn’t be a chance for me to support or help her. We all needed to do this in one take, lasting for 92 minutes. When I realised that there were some talents out there, and I knew it was possible to put together this group of actors, and when I found Andrea, I was quite sure that was the answer the question.

Andrea, there must have been a lot of pressure between being the focus of the film, and telling such a sensitive story. What was your experience during filming like?

Andrea, there must have been a lot of pressure between being the focus of the film, and telling such a sensitive story. What was your experience during filming like?

ANDREA: It was my first feature film, so that itself was scary. It’s the biggest national tragedy since World War Two, and that’s a lot of responsibility for a 19-year-old. Also being in one take, it’s a very challenging way of filming the movie.

But the thing that was most important to me was to have the survivors there and have their support. To have them there saying “we believe in this story, we want this movie to be out there, we want people to see the horror we went through. When we tell our story, people seem to listen but they don’t fully understand, so we can refer to this movie and then we can tell our story afterwards.” It was a very big motivation to have them there.

We rehearsed for about two months splitting the script into different scenes, sometimes with the camera as all the actors are amateurs so we’re not used to having a camera following us around, or sometimes being 10cm away from your face.

How did you work with survivors to tell their story correctly?

ERIK: It was important to have them on board from the very start. A mother contacted me as I was preparing the movie, and said “If you are able to make this work, it might actually help us make people understand what we’ve been through. But if you consider using this as a backdrop for a romantic story, I will never forgive you. Then you are creating popcorn entertainment out of what really happened out there. What happened out there is only one thing: young kids were killed, my daughter was killed out there, so if you do that I will never forgive you. I will follow you for the rest of your life.”

That was really quite clearly expressed. We put together a group of survivors who would be with me all the way. They would be there through the process of making the script. I held over 40 interviews with survivors, we did everything we could to create a reflection of how it was to be out there. Not a dramatic story, but a story that represented a lot of the young kids out there.

They showed up when we were in rehearsals with actors, and they were also present when we did the actual filming that week. That was the most important decision in this process to bring them along, and use them, and give them a director’s voice so they could come up with comments all the way.

You don’t hide away from the horrifying truth. A moment that really stands out is the slow death of one girl Andrea’s character stays with. Did you have any reservations showing such scenes?

For a long time, we have been watching movies where violence has been a huge part of our storytelling. It’s part of our entertainment industry to use violence in whatever circumstance. We also see violence in the news and the media today, we see violence all over. The fact is, we don’t seem to react to violence anymore, so I wanted to show a more truthful picture of what violence really is.

The way that someone dies in this film represents a much more truthful image compared to what you see in the movies all the time. I was quite secure about that, and I was also discussing that with survivors and the families that lost their loved ones. They were all able to read the script in detail, so it was important for all of us to show that, and then hopefully re-sensitise us to what violence really is.

Then again, it was the question to find the girl who could perform that scene, but with Andrea we thought that was possible. We were working in detail to make sure it was an honest representation. And I’m the first one to admit it’s a hard thing to watch, but then again it’s really an honest attempt to show you what that really is – dying, which people do in movies all the time. We hardly question that at all.

It’s an incredibly ambitious film, with one continuous shot throughout. It must have made filming much harder, why did you choose this approach?

All these young people we interviewed, so many of them shared the same feeling that those 72 minutes lasted for an eternity. Nothing happened, it was 72 minutes under constant attack on such a small island. It’s hard to imagine what that is.

I wanted to see if I could present time as an element, as a character in the film. That’s the only reason I wanted to do it one take. Technically it’s not hard to do it in one take, but when I see other movies do it, I very often wonder why they did it. I wanted to use it for this story because as soon as you add one cut, or add a piece of music, you can relax, you can tell yourself this is just a movie.

But at the same time I told the producers “please don’t use that as part of the marketing campaign”, I don’t want to focus on how the film was done. I just wanted bring the audience into the moment without any way of escaping. But that gave a huge challenge for actors.

The film ends with a warning about the rise of the far right in Europe. Why was it important to emphasise that message again, in case it was missed at all?

It was important to focus entirely on the victims, not to tell his story really. But still, it was important to end the film reminding people that this was a political attack made by a right-wing extremist. It seems to be important to remind ourselves that when we talk about white young men doing stuff like this, we think they are crazy or we use other expressions, we don’t fear them, we just shake our heads. When we think of terrorists, we think of people coming from other cultures attacking us, then we use the words like terror and we get afraid of what they’ll do to our society. But listen this is the largest attack on European soil since the Second World War, conducted by one man. It was a white Christian man, doing this political reasons.

It’s important to get that out there, but we also felt to get to know his story is to once again tell his story. I wanted to be careful not to give him more attention. I wanted to give attention to the victims. What he wants now he’s placed in a prison is just to get attention and get his message out there once again. We all have a responsibility to now focus on the victims and not him any longer.

The shooter barely appears in the film, was this part of avoiding glamourising him?

It wasn’t so much a deliberate choice of not wanting to show him; I wanted to show him as the young people experienced him – from the distance, with the sound of the gunfire getting closer and closer. This was deliberate because when he got closer, people tried to hide away, so I just wanted to reflect that in the way the camera behaving. Most of the people didn’t see him, if he was on top of you, you got killed. So I wanted to use that perspective deliberately, and I never wanted to intercut between the kids and his story. That was important for me to focus entirely on their perspective.

What I would really like to say, I think it’s important to discuss the ethics of making this movie. I really insist that we couldn’t wait any longer to tell this story, it was important to get it out there now. These young people are receiving messages in the mail saying that they are sorry the perpetrator didn’t kill them, that he didn’t succeed.

It seems that that type of language, this rhetorical climate in Europe, seems to be more and more normalised. It’s not even the right-wing extremism that uses this language. It’s become normalised in this political climate, politicians these days seem to express themselves in that way, so it felt quite important to get this film out now.

Also it was a story that wasn’t made just by me and our group of actors, but the victims and survivors were the ones who wanted to get this story made and supported the film through the whole process. It seems to be important to tell this story, to tell the younger generation what happened, but also remind people in our generation what really happened out there. It was important for ethical reasons to do this film, and tell the stories of the victims, not the perpetrator.

So this was not a film for your career, but doing whatever you could to help these survivors?

That’s actually what they expect. They wanted their story out there. When I presented the idea, they sort of came from all directions to me, and supported the idea of making the movie, as long as it was a story about what really happened, truthfully, about the victims. It could also help them to get out there and present what they’d been through, and remind all of us how we can support them, meeting them, getting back into their life.

- Utoya: July 22 is released in cinemas Friday 26 October

- Read more interviews on theartsdesk

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit